“Freedom is started from the inside”

Victor Rosario spent 32 years behind bars for a crime he says he did not commit. He returned to prison as a free man to share a walk—and a message of hope—with his old friends.

Victor Rosario spent 32 years behind bars for a crime he says he did not commit before a judge overturned his convictions. More than a decade after his release, he returned as a free man to the Massachusetts prison where he spent most of his incarceration. There, he shared a walk—and a message of hope—with his old friends.

On November 1, Rosario attended the Walk for Innocence at MCI Norfolk with his former attorney, Lisa Kavanaugh. The event was organized by one of Kavanaugh’s current clients, who is incarcerated there. According to Rosario, the walk was an opportunity to connect with “friends, brothers, [and] fathers” who hope to someday get out of prison.

“Because they are my family, it was so powerful, so amazing to be able to … walk with them,” he said.

Rosario was convicted of arson and eight counts second-degree murder after prosecutors accused him of setting a deadly 1982 fire in Lowell. However, a judge threw out the convictions in 2014, finding that new scientific evidence cast doubt on the voluntariness of incriminating statements Rosario made to police—and on whether the fire was arson in the first place. In 2023, the city of Lowell agreed to pay Rosario $13 million to settle a civil rights lawsuit that accused police coercing him into confessing and said the evidence was consistent with an accidental fire.

During Rosario’s time in MCI Norfolk, he joined a running club and trained to run marathons on a track behind the prison walls. He completed his first marathon—which required running 76 laps—in October 2013. That same year, during a meeting with Kavanaugh at MCI Norfolk, the two spoke about their shared love of running.

“In the prison, I think [running is] freedom,” Rosario said in a 2018 podcast. “It’s a moment that you are by yourself, a moment that you can meditate, a moment that you can go into your deepest thoughts … and [think about] something in the future. For me, it was everything.”

Kavanaugh said that Rosario’s story inspired her to register for the 2014 New York City Marathon. Just a few months before the race, a judge overturned Rosario’s convictions. After he was released from prison, he and Kavanaugh became training partners, she said. The experience led the two to create the Running for Innocence team to help get other wrongfully convicted people out of prison.

Every year, the team raises money by participating in the GenesisHR Battlegreen Run at Lexington High School, where members run in a 5k or 10k race or walk.

Kavanaugh is the director of the innocence program at the Massachusetts Committee for Public Counsel Services (CPCS), the state’s public defender agency. She said the money the team raises is used by the state’s three innocence programs—the CPCS program, the Boston College Innocence Program, and the New England Innocence Project—to pay for private investigators and expert witnesses.

The funds are useful, Kavanaugh said, because they allow lawyers to pay for investigations for their clients without going through the courts.

Since Running for Innocence was formed, money raised by the organization has paid for 53 investigations, according to information it provided. These efforts have helped free 16 people from prison, eight of whom have been fully exonerated, and assisted with 12 pending new-trial motions across the state.

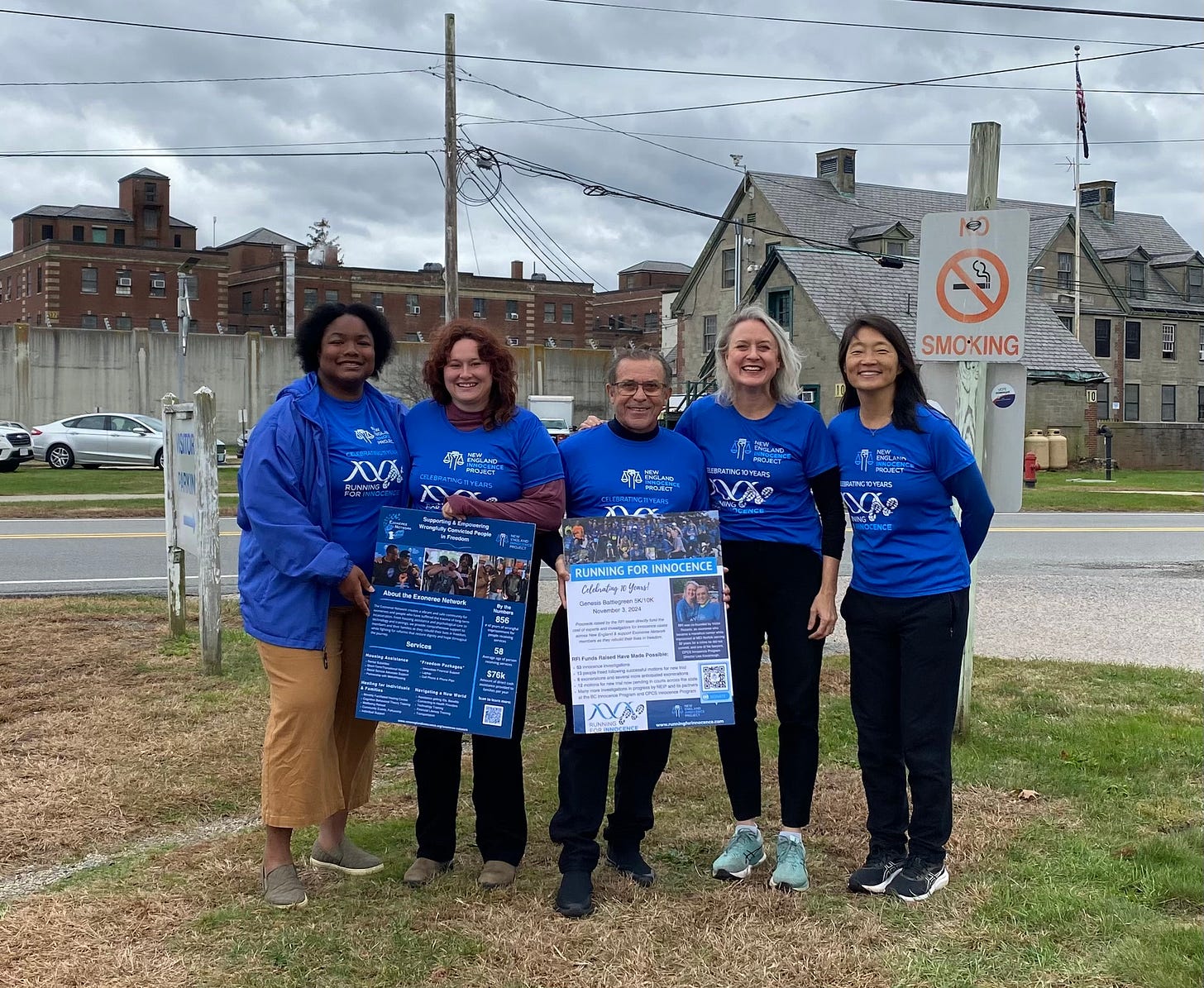

One of Kavanaugh’s current Innocence Program clients, Brian P.—who is being identified by his first name and last initial for his privacy at Kavanaugh’s request—was inspired by the team’s success. In 2024, he organized a Walk for Innocence behind the walls at MCI Norfolk, where he is incarcerated for a murder conviction that he is fighting to overturn. With permission from the Massachusetts Department of Correction, Kavanaugh and four other members of the running team took part in the walk with Brian P. and about 100 other incarcerated men.

This year, Brian P. was able to organize a second Walk for Innocence—along with a 5k race at the prison. The race took place the same day as the one in Lexington, and the 17 incarcerated men who participated were able to register as members of the Running for Innocence team, according to Kavanaugh.

Rosario, who said he moved to Puerto Rico about two years ago, had not participated in the Running for Innocence team since 2022.

“I go into the prisons in Puerto Rico doing the ministry and trying to give … hope to those that [are] still behind the wall,” he said. “And I will continue to the day I die.”

But this year, he returned to Massachusetts for a few days so that he could attend both the walk at MCI Norfolk and the run at Lexington High School.

“The reason I came back is because, one, I miss my friends,” he said. “I’m missing the organization. I know what the organization has been accomplish[ing] … and I am so happy just to come back and start running again because I [had stopped] for a while.”

And this year, according to Kavanaugh, Running for Innocence had its largest team yet, with more than 100 participants.

“Hope is Renewed”

The afternoon of November 1, Rosario, Kavanaugh, and three other members of the Running for Innocence team arrived at MCI Norfolk for the walk. It was the first time Kavanaugh and Rosario visited the prison together since his release.

“He and I walked right by the room where we first met each other and talked about this concept of running together if he ever got free and the dream of everything that’s come to be,” Kavanaugh said. “It felt very full circle to have both of us returning to Norfolk together.”

Before the walk, the visitors addressed the incarcerated men in the prison’s auditorium.

“A lot of friends of mine [are] still there,” Rosario said in an interview. “It was really painful [seeing them]. … And I just made sure to let them know that freedom is started from the inside, not … the outside.”

He said he thanked God that he was able to experience that sense of freedom even when he was in prison.

Kavanaugh told the men about how she and Rosario founded the Running for Innocence team and trained together after he was released, according to a copy of her prepared remarks.

“All of my longest training runs—16, 18, 20 miles—I ran with him at my side,” she said. “When I hit the proverbial running wall, he was there to help me past it. And in that process of training and completing the marathon, we began fundraising to help innocence lawyers across Massachusetts.”

Kavanaugh told the group that this year, money raised by Running for Innocence has helped free three men who were convicted of murder—James Carver, Eddie Wright, and Rickey “FuQuan” McGee. She said that she met Wright and McGee at MCI Norfolk in 2024 during the first Walk for Innocence and has since “had the chance to celebrate and work with [them] on the other side of the wall.”

Another attendee of the walk was Shar’Day Taylor, a social-services advocate for the Exoneree Network, an organization that helps obtain housing and other services for people whose convictions have been overturned.

Taylor is the younger sister of Sean Ellis, the director of the Exoneree Network and an exoneree himself. In 1995, after three trials, Ellis was convicted of murdering a Boston police detective. But in 2015, after Ellis spent 21 years in prison, a judge overturned his conviction due to evidence of police misconduct.

“The last time I was here [for the first Walk for Innocence], I met the person who had created the most beautiful birthday cards for me when I was a child,” Taylor said, according to a copy of her remarks. “I met people who I had heard stories about and who were influential to my brother’s growth and development. It was truly a magical moment for me, one that I don’t take for granted.”

She encouraged the men to take classes, participate in programs, study at the prison law library, and to avoid drugs.

“The weight you carry is heavy,” she said. “It can feel relentless. But you are not alone … Every year, we march the streets, holding up pictures and shouting the names of our loved ones behind the wall.”

After the visitors spoke to the men, they exited the auditorium to a paved area where they walked together. Kavanaugh said the visit was emotional not just for Rosario but also for the incarcerated men.

“People were wanting to hug him and were wanting to shake his hand and lined up to talk to him,” she said.

She said she also spoke with many of the men, some of whom asked for her support with bills at the State House.

“As a lawyer, I’ve gone to MCI Norfolk many, many times, but always to meet with one individual client,” she said. “To get the chance to meet so many people who I don’t represent, but who I’ve heard about, … [and] to just be able to shake their hands and have a short but intense conversation with them is really powerful. And it makes me realize how inaccessible we are to people behind the wall and how important it is to try to break down some of that barrier.”

The incarcerated men who participated in the walk donated more than $400 from their canteen accounts to Running for Innocence, according to Kavanaugh.

“It’s a huge amount of money, especially when you consider how little money people are paid for work assignments in prison,” she said. “It’s incredibly generous.”

Kavanaugh said she enjoyed spending time with Brian P. for something unrelated to their attorney-client relationship.

“I really relish the relationships that I form with clients,” she said. “It’s really special to get to see what he’s able to accomplish as a leader and to get to be a part of it. And I could just tell how proud he was to be able to pull this off.”

Two days after the walk, Brian P. and 16 other incarcerated men ran nine laps around a track at MCI Norfolk to complete their 5k race shortly before the Running for Innocence team gathered in Lexington.

“Participating in the walk on Friday and run on Sunday gave the wrongly convicted men behind the wall a small feeling of giving back and having some control,” he said in a written message shared with The Mass Dump. “When you are imprisoned for a crime you did not commit, helplessness and hopelessness is a daily battle often lost. The price is paid not just by the wrongly convicted, but by their whole family.”

He added: “When your case is accepted by an innocence organization like the [CPCS] Innocence Program, the BC Innocence Program, or the New England Innocence Project, everything changes. Hope is renewed. Entire families are given the gift of knowing that someone is in their corner, their voice is being heard, and the truth still matters.”

When the Running for Innocence team met outside Lexington High School, Kavanaugh played a recorded message from Brian P.

“We had a great turnout,” he said. “Guys were excited to be running in solidarity with the runners out there in the free world. It was their opportunity to show … how much we appreciate the fight to prove our innocence.”

Kavanaugh said she told Brian P. she “hope[s] more than anything that next year, he’s not organizing the Walk for Innocence at Norfolk, that he is participating in the Run for Innocence in Lexington.”

“This All Happened Because of You”

Rosario made the decision to return to Massachusetts shortly after the 2024 race in Lexington. That year, his old friend and running trainer from MCI Norfolk, Alex Rodriguez, joined the team and ran the race for the first time. After Rodriguez finished the 10k, Rosario said he would race him the following year—and he made good on his promise.

Before this year’s race, Rosario told the team that Kavanaugh outran him the first time they participated in an event together after his release from prison. He said that Rodriguez chided him for allowing a woman to beat him. Rodriguez and Kavanaugh laughed as Rosario told the story.

“We’re going to run together today, and that will be amazing for me,” Rosario said. “I can run with my own trainer.”

The race between the two men ended up not being much of a race at all. Rodriguez said they ran together—and sometimes slowed to a jog or walk—and talked about life. Both of them, Rodriguez said, could stand to lose some weight.

“I just told him, he needs to do a little more running, because he’s a little heavy,” Rodriguez said with a chuckle.

By the end, both were running, and Rodriguez—who’s more than a decade younger—finished shortly before Rosario.

“He always beat me up,” Rosario said. “He’s the best.”

In 1999, when Rodriguez was 19 years old, he shot and killed a convenience-store clerk during a robbery, a crime for which he says he has accepted responsibility. He pleaded guilty to second-degree murder the following year. He was released from prison in January 2023 after being granted parole.

He said that Rosario became his closest friend in prison after he met him through the running club at MCI Norfolk in 2004.

“We spent pretty much almost every day either walking the yard or running together,” he said. “It was a lot of years.”

He said the two participated in programs together and connected through religion even though he’s Catholic and Rosario is protestant. He said his friendship with Rosario was life-changing and encouraged him to better himself.

Stephanie Hartung, a lawyer with the New England Innocence Project, also addressed the team before the race. She welcomed her client, Eddie Wright, who spent 41 years in prison before a judge overturned his murder conviction in April. He was released from prison in July.

“Last year, … I was holding a sign for our longtime NEIP client, Eddie Wright,” she said. “But Eddie couldn’t be with us. He was about 50 miles away, sitting in a cage in Norfolk, sentenced to die in prison. But today, in part with help from the funds from [Running for Innocence], Eddie has been released and exonerated, and today he’s here with us.”

She added: “Eddie’s case is just one example of tens of thousands of dollars spent on investigators, DNA testing, [and] experts. … Every penny, every cent, is worth it. But for everybody who’s here, everyone who’s exonerated or freed but fighting, we know that there are dozens more still in prison fighting, trying to prove their innocence.”

“Seeing everyone here,” she said, “it feels like an act of resistance to a prison system that is focused on keeping people isolated and on dehumanizing people.”

Wright, who walked that day, said the event was an “uplifting experience.”

“It was great that so many people turned out for [it] and participated,” he said.

One of Kavanaugh’s clients, James Carver, also appeared at the race for the first time. Much like Rosario, Carver was convicted of arson and multiple counts of second-degree murder. Carver spent 36 years in prison, but a judge overturned his convictions in December and freed him in February.

But Carver, who uses a wheelchair, said he didn’t participate because he didn’t have the right kind of chair. When Kavanaugh welcomed him, he joked that he planned to run the race.

“I’m healed,” he said, raising both hands. “I’m healed.”

Kavanaugh said it was wonderful having Carver attend the race. But she said that when she invited him, he said he wasn’t sure why she wanted him to be there.

“I was like, What do you mean why do I want you there?” she said. “Last year I was holding your sign, and you were still in prison, and this year you’re free. That’s why I want you there.”

Kavanaugh said the race organizers gave a medal to everyone who finished, and she gave hers to Carver.

“He was like, I shouldn’t have this. I didn’t do the walk,” Kavanaugh said. “And I said, Of course, you should. You’re here. You’re part of this team.”

Kavanaugh said she was also excited to see Rosario so that she could share news about the recent accomplishments of the Running for Innocence team and the Exoneree Network, which Rosario helped found in 2020.

“It was so amazing to … feel like I was able to honor him and make clear to him, like, This is happening. This all happened because of you, Victor,” she said.

“The growth has been so organic and natural and beautiful,” she said. “And it kind of feels almost unstoppable. You know, there’s so much negative in the world, and this is just this overwhelming positive thing that keeps getting more positive.”

She added: “It’s happening at the community level, but I’m also excited to see that it’s happening in the cases themselves. … Literally, the court decisions are helping other people. … You have Victor’s case being cited in FuQuan’s case.”

Rosario said that when he saw the Running for Innocence team gather in Lexington, he was surprised by how large it had grown—and he knew he had done the right thing by helping found it more than a decade ago.

On October 30, Rosario’s first night back in Massachusetts, he attended Jammin’ for Justice, an annual concert organized by the running team and the Exoneree Network. The event raises money to send exonerees from Massachusetts to the Innocence Network Conference in Chicago.

“To be honest with you, I feel like I was so completely out of place because I just stayed for two years out of Massachusetts,” Rosario said.

But when he saw everyone having a good time and uniting for a common purpose, he said, it made him feel happy. He got on stage to address the crowd, telling them he felt “like a butterfly.”

He briefly talked about his work with incarcerated men in Puerto Rico. The men, he said, have told him that the Massachusetts prisons where he was incarcerated were “like a paradise” compared to Puerto Rican prisons.

“I am not going to glorify prison, because prison is not made for a human being,” he said. “I use the word we with them to let them know that I know the pain, and I know the suffering, and I know the loneliness, and I know the cold—and that is real, real, real, real pain.”

“But,” he added, “[I’m] just so grateful for so many people that care like me, like you right now.”

Thanks for reading! Journalism like this takes a ton of time, energy, and care. If you’d like to keep The Mass Dump running, please consider offering your financial support, either by signing up for a paid subscription to this newsletter below, becoming a Patreon supporter, or sending a tip via PayPal or Venmo. I rely on your support to keep doing this work, and a monthly subscription is just $5!

Even if you can’t afford a paid sub, please sign up for a free one to get updates about this story, and please share this article on social media.

You can follow me on Bluesky and Mastodon. You can email me at aquemere0@gmail.com.

That’s all for now!