Science Proves Man Convicted of “Worst Mass Murder in Massachusetts History” Is Innocent, Lawyers Argue

James Carver is serving life in prison for a deadly fire but for decades has insisted he is innocent — and his lawyers say they have the scientific evidence to prove it

Content Warning: This story includes discussions of death, suicidal thoughts, illness, drug and alcohol addiction, and sexual harassment. If you or someone you know may be considering suicide or is in crisis, call or text 988 to reach the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.

It was the early morning of July 4, 1984. Beverly police officer Duane Hathaway was driving down Rantoul Street when he heard the owner of the Sunray Bakery screaming to get his attention. Hathaway turned his cruiser around then came to a stop, and the owner pointed to a rooming house a few blocks away.

It was on fire.

Fifteen people would be killed by the inferno, the deadliest in Massachusetts since the 1942 Cocoanut Grove blaze. And eventually, a Danvers man would be convicted of setting the rooming-house fire and sentenced to life in prison for what The Beverly Times described as the “worst mass murder in Massachusetts history.”

But that man, James “Jimmy” Carver, has insisted on his innocence for the last 34 years. And now his attorneys think they can prove it. They argue that new science shows the prosecution’s theory of how the fire started is impossible and casts doubt on crucial eyewitness testimony that helped put Carver in prison. They also have newly released records showing that Carver’s trial attorney admitted to a serious drug and alcohol problem at the time he was working on the case.

This is the story of a tragic fire that killed 15 people and of the investigation that put James Carver in prison for decades — and the hope he and his family now have for his exoneration.

It’s a story told in a massive collection of documents reviewed by The Mass Dump, including newspaper articles, photographs, public records, court records, trial transcripts, and a secret court file that includes hundreds of police reports and grand jury transcripts.

At 4:18 AM, Hathaway radioed the police station that he was investigating a fire in progress then raced a half-mile to the source: the Elliott Chambers Rooming House.

The three-story building, located at the corner of Rantoul and Elliott, contained the Davis Drug pharmacy, a barbershop, a TV repair shop, and a law office on the first floor. The two upper floors functioned as a rooming house where 36 people lived, among them some of the city’s poorest residents. Some were psychiatric patients placed in the building by the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health. The “rooming house … served as a home of last resort for many luckless people,” as The Beverly Times would put it the following day.

When Hathaway arrived, he saw “flames shooting out from the front entrance” and “billowing straight up to the second and third floors,” according to his written report.

Firefighters arrived moments later and began an hours-long battle to rescue trapped residents and extinguish the blaze. Before firefighters began applying water, they used ladders to save nine people, some of whom were hanging from windows. A few people jumped instead of waiting for help. Others went deeper into the burning building instead of remaining at the windows, and “firefighters were nearly sobbing with frustration” when they were unable to save them, according to The Beverly Times.

Despite the efforts of first responders, 14 people died that morning, most from burns or smoke inhalation. One man jumped from a third-story window, hit a traffic-control box, landed on the pavement right in front of Hathaway moments after the officer arrived on scene, and was pronounced dead on arrival at a local hospital. A fifteenth victim — who emerged from the building as it blazed, his body badly burned — died of respiratory failure a month later.

One day after the horrific fire, officials informed the media that they believed someone deliberately started it by burning a bundle of newspapers in the alcove containing the rooming house’s entrance. Within days, an anonymous tip led investigators to a suspect: James Carver, a 20-year-old Danvers resident who worked for a taxi company and a pizza place in Beverly.

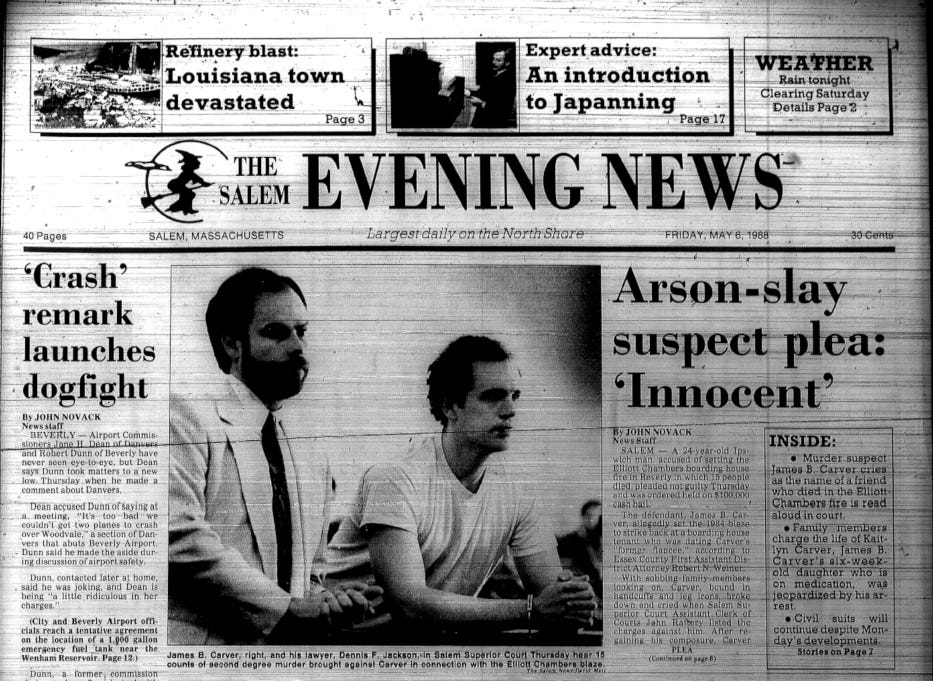

However, it would be nearly four years before Essex County First Assistant District Attorney Robert Weiner indicted Carver and police arrested him. Finally, in March 1989, Carver went on trial. Weiner alleged that Carver was upset because his ex-fiancee had dated a man who lived at the Elliott Chambers and set the fire in a jealous rage. Carver’s parents testified that he was sleeping at home when the fire broke out.

Carver was represented by Dennis Jackson, a defense attorney who handled murder and felony cases in Essex County. After three weeks of testimony, Superior Court Judge Peter Brady declared a mistrial when it came to light that Weiner withheld reports showing a witness made contradictory statements to police.

The victory was short-lived. Carver, still represented by Jackson, was tried again in November 1989 and convicted of arson and 15 counts of second-degree murder. Judge Cortland Mathers, who presided over the second trial, sentenced Carver to two consecutive life terms.

But now, decades later, a judge has agreed to hear new evidence that Carver’s current lawyers say will show the fire likely wasn’t murder at all. There is no physical evidence the blaze was arson and it might have actually been an electrical fire, they argue in court documents filed in March 2022 and January 2024.

The lawyers further argue that Carver was denied a fair trial because his original lawyer, Jackson, “was unfit to represent any client, much less a client facing such serious charges,” due to his drug and alcohol problem and other misconduct that led to him losing his law license.

They cite records uncovered by The Dump in which Jackson said his substance-use problem was so severe that he could not think or act rationally. They also cite records showing Jackson was accused of harassing teenage girls, one of whom was related to a defense witness in the Carver case. The lawyers argue that the harassment allegations lend support to an allegation that Jackson had an inappropriate sexual relationship with Carver’s wife while representing him, an accusation that a judge rejected during a previous attempt at overturning his conviction.

Carver was 25 when he was convicted. Now 60, he has spent most of his life in prison.

“If I were guilty, I would have taken the [plea] offer,” Carver told North Shore Sunday from prison in a 1996 interview. “But I am innocent and I will fight this.”

Carver’s trial attorney, Jackson, died at the age of 55 in 2010.

Bill Carver, James Carver’s youngest sibling, told The Dump in a recent interview that his brother’s prosecution and incarceration profoundly impacted their family.

Their parents, Roger and Gail Carver, lost their Danvers home to foreclosure in 1992 due to legal bills related to the criminal case, according to North Shore Sunday. Both parents are now deceased.

“The house … doesn’t belong to my family, or my father, or his estate because they paid that attorney,” Bill Carver said, referring to Jackson.

The life sentence also prevented James Carver from raising his daughter, who was born less than two months before he was arrested, Bill Carver said.

He compared his brother’s case to the Salem Witch Trials, the most infamous wrongful convictions in the history of Essex County.

“I had a lot of confidence in the justice system and government before this all happened to my brother,” he said. “But what I got was the reality of it’s not quite what it’s cracked up to be, that it’s a human institution with a lot of failures.”

Investigative journalism like this takes a ton of time, energy, and care. Please consider signing up for a paid subscription to The Mass Dump newsletter below, becoming a Patreon supporter, or sending a tip via PayPal or Venmo to make more work like this possible.

“Justice May Not Have Been Done”

Carver is now represented by Lisa Kavanaugh and Charlotte Whitmore, two lawyers dedicated to exonerating innocent people whose lives have been turned upside down by the criminal legal system.

Kavanaugh is the director of the innocence program at the state’s public defender office, the Massachusetts Committee for Public Counsel Services. Whitmore is a staff attorney at the Boston College Innocence Program.

Kavanaugh and Whitmore declined to comment on the case or make Carver available for an interview, citing their efforts to prepare for the upcoming hearing.

The lawyers’ March 2022 motion for a new trial is Carver’s fifth attempt at overturning his conviction. However, it is the first attempt by his current legal team — and the first attempt to use scientific evidence to challenge the prosecution’s theory that the fire was arson.

In Massachusetts, a judge “may grant a new trial at any time if it appears that justice may not have been done,” according to the state’s rules of criminal procedure. Lawyers must either present important evidence that was not available at the time of the original trial or show that the defendant’s trial lawyer was unusually ineffective. Even if an issue is insufficient on its own to overturn a conviction, a judge can consider how the “confluence” of multiple problems affected the trial’s fairness, according to a 2015 Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruling.

The first step of overturning a conviction is to convince a judge to hold an evidentiary hearing at which defense attorneys and prosecutors can present new testimony from experts and other witnesses. If a judge believes the issues are serious enough to warrant a hearing, they will listen to the testimony and arguments from both sides then decide whether the evidence is compelling enough to throw out the conviction. If the judge does so, prosecutors can appeal, call for a new trial, or drop the charges.

In court documents filed in September, Catherine Semel, the Essex County assistant district attorney who is now handling the case, acknowledged that there is no physical evidence the fire was started with a flammable liquid like gasoline and that an arson investigator gave erroneous testimony. However, she argues that Carver is not entitled to a new trial because there’s still enough evidence to show he is guilty.

Nevertheless, Semel agreed that both sides should have the opportunity to present new expert testimony in court.

A spokesperson for Essex County District Attorney Paul Tucker did not respond to a request for comment.

Essex County Superior Court Judge Jeffrey Karp agreed to hold a multi-day hearing that begins Tuesday. At a conference in November, Karp told Carver’s lawyers that he was eager to hear the scientific testimony.

“I’ve read the briefs, and there’s some really forensically interesting — at least to me as a forensic geek, I guess — issues that you’ve raised,” he said.

The original prosecutor, Weiner, declined to comment when reached by phone in March 2023 and has not responded to messages since Karp ruled to hold the upcoming hearing.

“I really have nothing to say,” the now-retired prosecutor said, adding that it was a very old case.

During the two trials, Weiner built his case around James Carver’s purported motive of wanting to kill 21-year-old Richard “Rick” Nickerson for dating Carver’s ex-fiancee.

Nickerson lived at the Elliott Chambers with his grandmother, who managed the rooming house. Nickerson’s nine-year-old brother, who lived in Auburn, Maine, was visiting for two weeks at the time of the fire. All three died in the blaze, with Nickerson’s brother being the youngest victim.

One of the prosecutor’s key witnesses testified that she was a former friend of Carver’s and that he had invited her to his home in October 1984 and made a tearful confession. Carver, the witness testified, said that he set a fire by pouring gasoline on newspapers and burning them with a match.

Carver said that he didn’t mean to hurt anyone and was only trying to scare his ex-fiancee and Nickerson because he was upset about them dating, the witness said. Carver never specified which fire he was talking about but the witness understood his comments to be about the Elliott Chambers, she said.

She acknowledged in her testimony that she never went to the police after Carver allegedly confessed to her. Instead, she said, investigators called her in March 1987 after she moved to New York, and she then told them about the alleged confession for the first time.

After Carver was arrested in May 1988, Kevin Burke, who was the Essex County district attorney at the time, said at a press conference that the witness’s statement to police was what finally made it possible for his office to file charges.

“It was the kind of statement that allowed us to put together all the other corroborative evidence and fit the pieces of the case together,” Burke said, according to The Salem Evening News.

Semel argues the testimony from the former friend and other witnesses who said Carver threatened Nickerson or talked about wanting to kill him is strong enough evidence to prove he is guilty regardless of the new fire science.

But Kavanaugh and Whitmore argue that the new scientific evidence “completely undermines” the alleged confession because it shows the fire could not have started on the newspaper bundle. The lawyers write that modern scientific testimony would have given jurors reason to conclude either that the former friend was lying or that she was telling the truth but that Carver’s alleged confession wasn’t true.

When Jackson gave his closing argument during the second trial, he did not dispute that Carver made the alleged confession. Instead, the defense attorney told the jury that Carver “was crying out for help” because he had been under investigation for months, was the subject of constant rumors, and “just couldn’t bear being accused of this any more.”

Carver had been drinking, was extremely emotional, and said he wanted to kill himself when he made the alleged confession, according to the witness’s testimony.

“Everybody was believing he did it,” Jackson said. “Nobody was saying he didn’t do it. Put yourself in his shoes. When you are accused of something repeatedly, doesn’t it get a lot easier just to say: Yeah, I did it?”

Kavanaugh and Whitmore argue that if Jackson had access to modern fire science, it would have completely changed his trial strategy by allowing him to effectively attack the reliability of the alleged confession.

“The newly discovered evidence presented [here], weighed against the evidence presented at trial, raises more than a substantial risk that justice was not done in this case,” they write. “Mr. Carver is entitled to a new trial where the jury is presented with this newly developed evidence.”

“Mere Say-So Assertions”

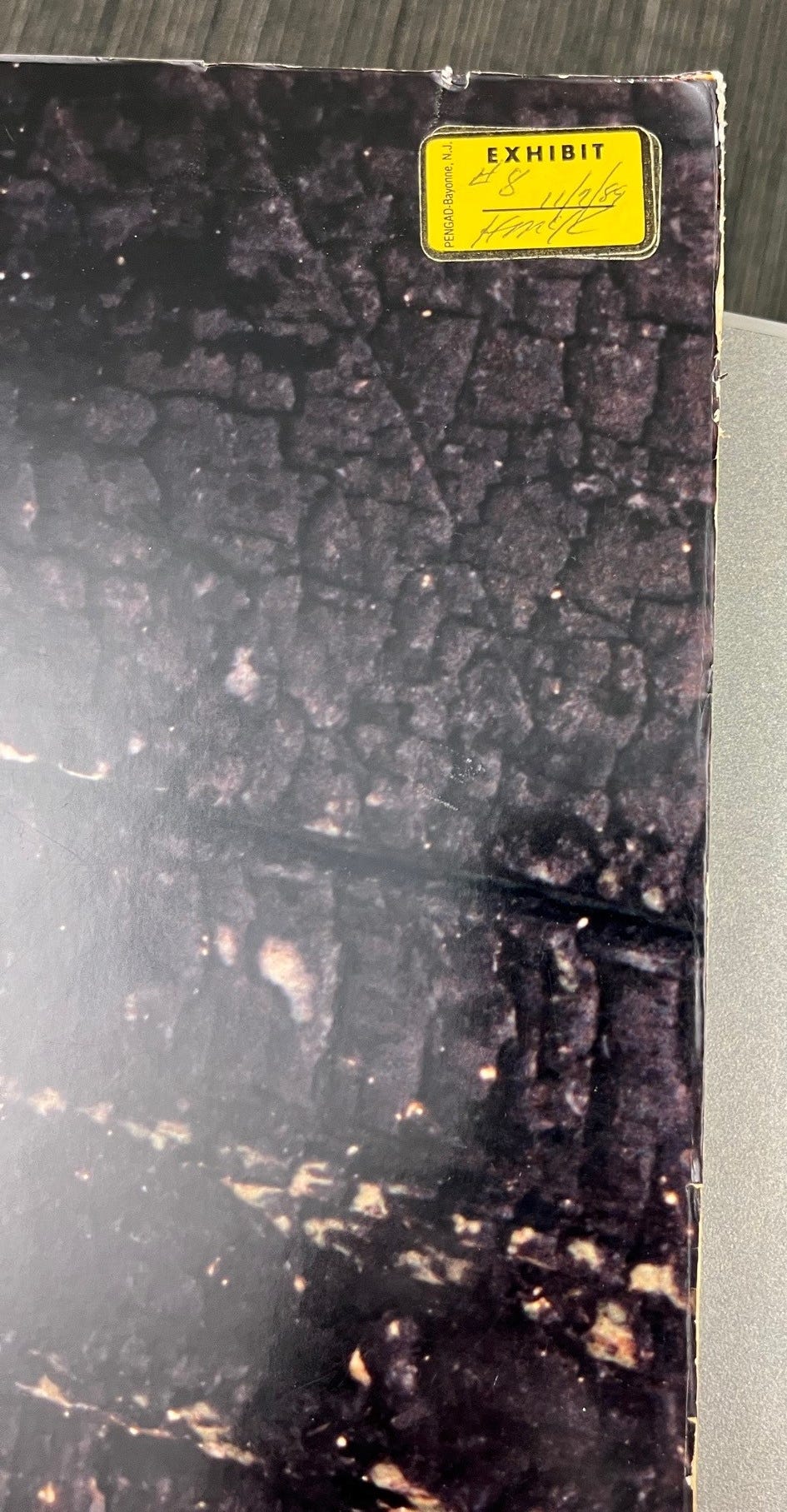

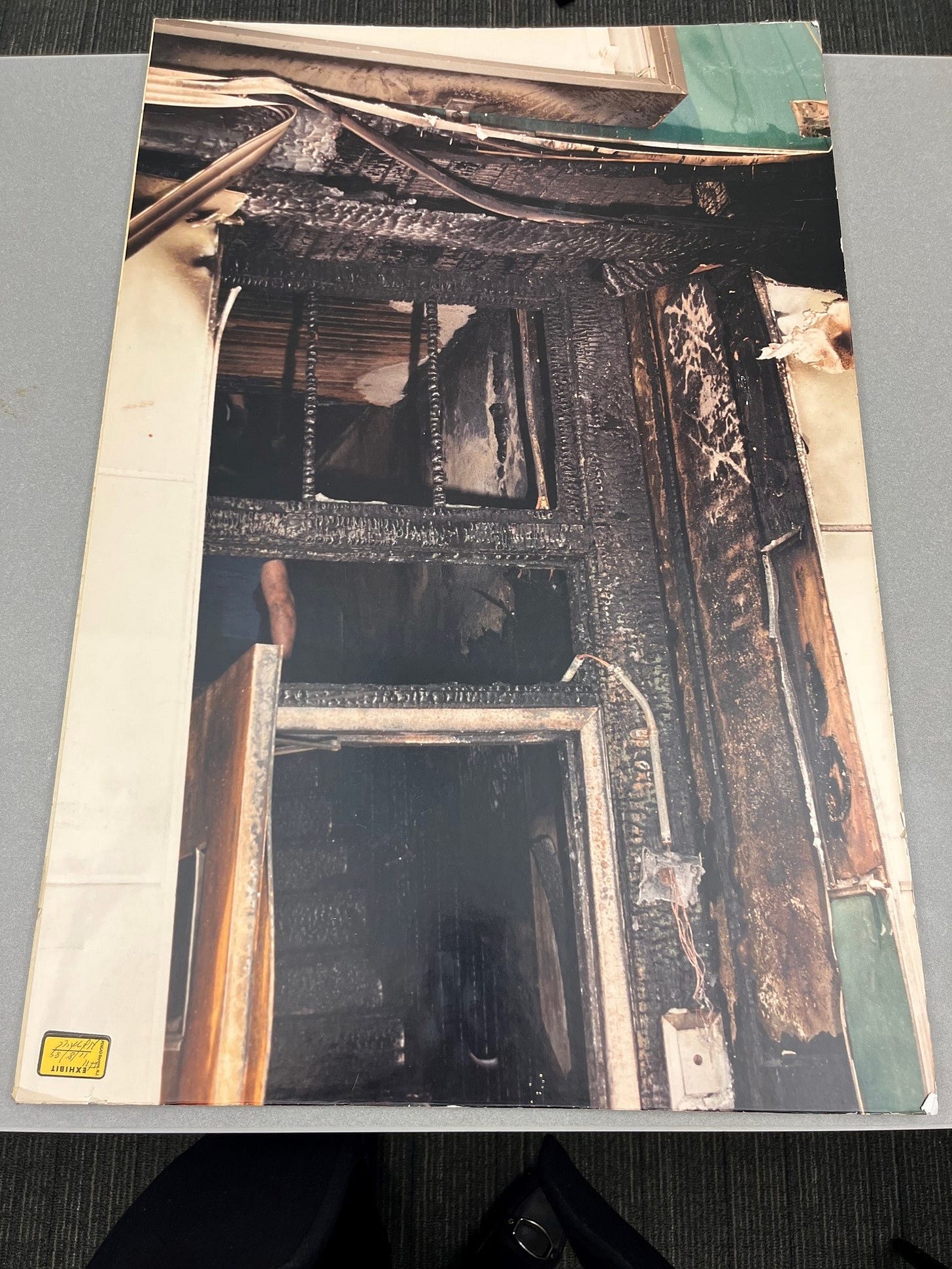

Immediately after the blaze, investigators examined the charred remains of the Elliott Chambers in search of clues about the fire’s origin and cause. Two investigators concluded that the fire was deliberately set on a bundle of newspapers that a firefighter found in the alcove that contained the entrance to the rooming house’s stairway. The firefighter later testified that the bundle was blocking the entrance as the fire raged, and he had to kick it out of the way to open the door.

However, a fire expert who reviewed the case for Carver’s legal team believes the fire started in the alcove’s overhead and that the investigators failed to prove that it was deliberately set or to collect enough evidence to rule out electrical causes. Kavanaugh and Whitmore argue that the expert’s testimony, which is based on scientific ideas that were not understood in the ’80s, would have made a difference if it could have been presented to the jury.

The Elliott Chambers was initially examined by James Bradbury, a Massachusetts State Police trooper assigned to the state Fire Marshal’s Office. Bradbury concluded that the fire started on the newspapers and spread upward before engulfing the upper floors, according to police records. Bradbury filed a report but did not testify at either of Carver’s trials.

On July 9, 1984, four days after officials told the public they suspected arson, Robert Doran, a deputy chief fire marshal for Nassau County in New York, arrived in Beverly to begin his own two-day examination of the building. Doran was a member of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms National Response Team, which investigated major fires when local officials requested federal assistance.

Doran is now deceased.

Doran testified that the fire spread up the walls of the alcove and the heat broke the glass transom above the doorway. The flames, he said, were then sucked through the transom into the open stairway in a “chimney-type effect” and traveled to the second and third floors.

The first floor was largely undamaged other than the alcove and stairway, Doran said. The second floor was damaged extensively, and the third floor, cockloft, and roof “were almost entirely destroyed,” he said.

Like Bradbury, Doran determined that the fire was started on the newspapers. However, Doran made another crucial conclusion: He testified that the papers had to have been doused with a flammable liquid like gasoline before they were burned.

When trying to determine where the fire started, Doran said, he first looked for the lowest point of burn because “fire will not burn down.” He said that the lowest point of burn was the alcove.

Doran said that he observed “alligator charring” blisters — which are named after their resemblance to scaly skin — on the walls of the alcove. He said that higher temperatures cause larger alligator marks and that the blisters grow deeper the longer the fire burns. The blisters in the alcove were “fairly large” but had “no depth of char,” Doran said, “which indicated a high temperature.”

“There had to have been some other fuel present that generated very quickly over a short period of time high temperatures,” Doran said.

He also said that he observed “smoke swirling” stains on the walls of the alcove, which he said were “consistent with hydrocarbons which are present with flammable liquids.”

A state chemist could not find any traces of flammable liquids. The chemist testified that he tested samples of the newspapers, the concrete floor of the alcove, wood from the alcove, and soot wipings from the stains, but they all tested negative.

Doran testified that the lack of positive test results made no difference in his opinion because the flammable liquid would have been washed away by the water firefighters used to extinguish the blaze. And he said that because the soot samples were taken days after the fire, any liquid that caused the stains would have evaporated.

However, a retired fire-safety engineer who reviewed the case for Carver’s legal team says Doran relied on myths about fire that were commonly cited by investigators in the ’80s but have since been discredited by scientific research. And a retired investigator who reviewed the case for the district attorney’s office similarly concluded that Doran relied on since-debunked myths.

Craig Beyler, who is technical director emeritus at the consulting company Jensen Hughs, was asked by Carver’s lawyers to look at reports, witness statements, testimony, and photos related to the fire. He documented his opinions in two reports from March 2023 and January 2024. In his first report, he describes how fire investigation initially developed as “an oral, experience-based tradition” among firefighters who lacked scientific training, but it has since adopted an approach based on the scientific method.

“In 1984, the discipline [of fire investigation] was dominated by myths and folklore concerning the meaning of fire generated damage patterns and other fire effects,” Beyler writes.

Michael Mazza, a retired State Police fire investigator who reviewed similar evidence for the district attorney’s office in 2023, agreed that there isn’t enough evidence to show a flammable liquid was used, according to his report. Both Mazza and Beyler write that it’s a myth that fire cannot spread downward, and they both write that alligator charring and smoke swirling stains are not evidence of a liquid accelerant.

However, their agreements largely stop there. Mazza still concluded that the fire was “incendiary in nature” and caused by “the application of an open flame to the pile of introduced newspapers at the base of the alcove,” he writes.

According to Mazza, the newspaper theory is supported by photos showing a largely undamaged area on the lower portion of the walls in the right-hand corner of the alcove. This area was left undamaged because the newspaper bundle was pushed into the corner and protected the wall, Mazza writes. Because the newspapers were wedged in the corner, the fire would have burned more intensely than if the papers were positioned away from the walls, Mazza writes.

But Beyler writes that the fire actually started in the area above the alcove, and its cause is unclear and could have been electrical. Beyler writes that the damage to the alcove is consistent with a “drop-down fire,” which is when fire is spread by flaming debris that falls from a higher level of a structure to a lower one.

And according to Beyler, it’s physically impossible for the newspapers to have generated a flame powerful enough to have spread to the wood-panel walls of the alcove even if the bundle was in the corner. Research has shown that, for the fire to have spread to the wood, it would’ve taken flames that were at least five feet tall and burned “for a sustained period of time,” Beyler writes.

“While individual sheets of crumpled paper are easily ignited by an open flame, they are less than a foot in height and burn out in seconds,” Beyler continues. “When newspapers are piled and bundled, it becomes difficult to burn the paper. The bundle will include paper edges that can be ignited, but these edges are consumed in seconds of burning such that the paper bundle becomes a paper brick or block. In this form, paper does not readily burn.”

The twine holding the bundle together would have burned through if the newspapers had been used to start the fire, Beyler writes. The delivery driver who dropped off the newspapers testified that he tied them together. And the firefighter who discovered them described them as “a bundle” in his testimony, saying they were not on fire when he found them and he thought they were still tied together.

Mazza writes that there is no evidence of a drop-down fire or an electrical fire because Doran and other investigators said they ruled them out at the time.

Beyler writes that Doran incorrectly excluded electrical causes for the fire because he did not examine any electrical devices other than some wires hanging in the alcove. Furthermore, Doran’s examination of those wires demonstrated his “poor understanding” of how electrical fires start, according to Beyler.

Doran testified that he checked the wiring and found no evidence of a malfunction. He said that if there had been an electrical short, the wiring would have heated and become brittle, but it remained flexible, did not change in diameter, and did not exhibit any arcing or sparking. He also said that the wiring could not have overloaded because it did not develop beading or bubbles.

Beyler writes that Doran’s testimony that flexible wiring cannot be the cause of a fire “is scientifically incorrect.” And, Beyler writes, overloading wires are rarely the cause of electrical fires, and Doran did not rule out other more common causes.

“[Doran] never examined the circuit breaker box to assess what breakers had operated,” Beyler writes. “He failed to seek information about [other] devices and wiring in the alcove, the alcove overhead, and the stairway. Because he had no idea what devices and circuits had been present before the fire, he was unable to determine if any of the devices or circuits had caused the fire.”

Doran testified that he ruled out a drop-down fire in the alcove, saying, “The ceiling area was intact for the most part.”

But photos show the alcove’s overhead suffered damage that “would readily give rise to the drop-down of burning materials to the floor,” Beyler writes.

“The damage in the overhead is extensive, including burnthrough of structural members, while the damage near the floor of the alcove is superficial,” Beyler writes. “This is inconsistent with a fire starting at floor level and is consistent with a fire starting in the overhead.”

Bradbury, the first investigator who viewed the building, wrote in his report that he eliminated electrical causes because he did not find any “electrical devices … at or near the floor area” of the alcove. He also wrote that he found no “evidence of drop-type fire in [this] area” but provided no further explanation of what he did.

Bradbury also asked a state electrical inspector to examine the building. The electrical inspector wrote a report saying he checked the alcove, the entrance, the stairway leading up to the second floor, the service and meter equipment, and a fluorescent Davis Drug sign above the alcove. According to his report, he found no evidence of electrical malfunctions, but he did not explain how he reached this conclusion other than saying he checked the alcove’s overhead and did not notice any lights or wiring.

Mazza also points to photos showing that the lights inside Davis Drug and the store’s two outdoor signs were still lit up while the building burned.

Beyler writes that the electrical investigations Mazza cites are “mere say-so assertions” that were “made with no description of … electrical artifacts, no diagrams of the electrical system, [and] no photographs of electrical devices.”

The lights and drugstore sign cited by Mazza are a red herring, according to Beyler. He writes that these lights and signs would have been connected to the drugstore’s electrical circuit. The drugstore was located on the first floor, was not significantly damaged, and its circuit “was not involved in the fire,” Beyler writes.

And, Beyler writes, the undamaged area in the corner of the alcove is consistent with materials falling from the overhead on top of the newspaper bundle.

Semel, the assistant district attorney, criticizes Beyler, saying his “assessments … are necessarily hampered by their being based upon imperfect information, almost 40 years after the fact, by a person who never viewed the scene, never viewed the actions of the investigators he is critiquing, and who has instead, pieced together statements from a variety of sources, which, though voluminous, are not, themselves, complete.”

But, Kavanaugh and Whitmore write, Semel “fails entirely to acknowledge that Mazza’s analysis is ‘hampered by’ the same issues, and instead accepts without any corresponding hesitation his opinion that the electrical examination done by the original investigators was complete and that they correctly eliminated electrical causes.”

Semel argues that many of the concepts raised by Beyler, like drop-down fires and electrical causes, were understood in the ’80s and are not newly discovered evidence that would entitle Carver to a new trial.

Semel writes that Jackson, the trial lawyer, used “a reasonable defense strategy of challenging who committed the arson, rather than whether an arson had been committed.” She argues that the defense attorney could have hired an electrical expert to testify about the investigation, and his decision to not do so gave up Carver’s right to challenge the scientific issues raised by Beyler.

However, Kavanaugh and Whitmore argue that Jackson “could not have presented an appropriate arson witness at trial even with the exercise of due diligence.” Modern scientific ideas about fire, including the rejection of “alligator charring” and “smoke swirling” as evidence of an accelerant, had not yet been developed at the time, they write.

Kavanaugh and Whitmore also argue that because the district attorney’s office has changed its theory of the case by now claiming that it’s possible for the fire to have started without the use of a liquid accelerant, Carver is entitled to have this new theory put before a jury.

“It’s One of These Two Here”

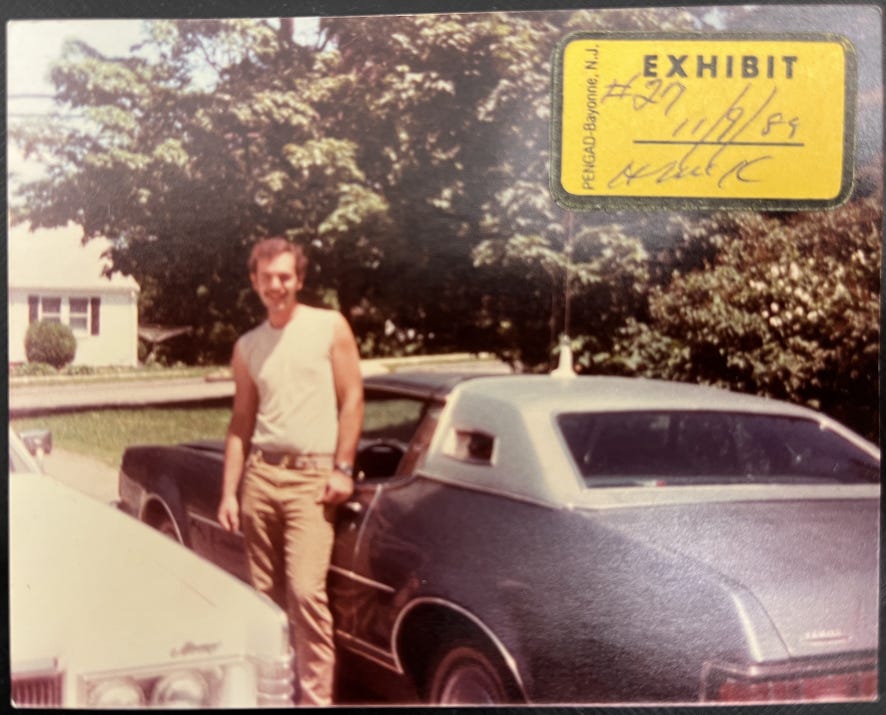

Another key witness for the prosecution was a cab driver who testified that he drove by the Elliott Chambers shortly before the fire started and saw James Carver standing next to the alcove where the newspapers were found. He also testified that he saw a car similar to Carver’s blue 1974 Mercury Cougar parked near the building.

“I’m sure this is the guy,” the cab driver recalled saying after selecting Carver from a photo array, a set of pictures used in the place of a traditional police lineup.

But there were significant problems with the cab driver’s testimony. His account of what he saw changed and grew more detailed over time. And, most strikingly, he actually selected Carver from the photo array after selecting someone else who was not a suspect, according to police records.

Investigators also made leading comments and subjected the cab driver to suggestive identification procedures that can cause false identifications, according to a January 2022 report by Nancy Franklin, a retired Stony Brook University psychology professor. Franklin, an eyewitness-memory expert, reviewed police records and testimony for Carver’s legal team.

The use of eyewitness identifications in court has come under significant scrutiny since 1989, when a judge first overturned a conviction on the basis that DNA evidence exonerated the defendant. Research has shown that it’s incredibly common for people to make mistakes when trying to identify strangers and that such errors are a leading cause of wrongful convictions. Faulty eyewitness identifications were a contributing factor in about 27 percent of known wrongful convictions since 1989, according to data collected by the National Registry of Exonerations.

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court took notice of this problem and established the Study Group on Eyewitness Evidence, which recommended best practices for investigators when interviewing witnesses and jury instructions for evaluating testimony in a report published in 2013 — some 23 years after Carver was convicted.

Even though this research wasn’t available at the time, many of the problems with the cab driver’s testimony did not go unnoticed at trial.

In Jackson’s closing argument during the second trial, he told the jury that the cab driver “didn’t know who he was picking” when he selected the two photos from the array. He argued that the cab driver “built a description against James Carver and the motor vehicle on every subsequent meeting that he had with the State Police.” He called the cab driver a “total liar,” saying his testimony was “totally unbelievable” and “should be thrown right out the window.”

But Kavanaugh and Whitmore write that if the recent research highlighted in Franklin’s report had been available, it would have allowed Carver’s attorney to “argue to the jury that even if [the cab driver] was testifying truthfully, and genuinely believed that his identification was correct, his identification was nonetheless scientifically unreliable.”

The cab driver, when asked by Jackson about discrepancies in his account of what he saw, testified that his memory “developed” after he first spoke with police and that he “remembered many different things as time went on.”

However, research shows that human memory tends to become less reliable over time, according to Franklin. The changes in the cab driver’s memory “likely … resulted from inferences, assumptions, [and] details he was exposed to after the incident,” she writes. The cab driver’s “pattern of statements point to the likelihood that [he] is particularly suggestible and prone to high-confidence memory intrusions,” she concludes.

Law enforcement did not interview the cab driver until more than a week after the fire and did not administer a photo array for a month and a half, which presented a “substantial opportunity for forgetting,” according to Franklin.

In the cab driver’s first statement to police on July 13, 1984, he said he drove by the Elliott Chambers in his taxi around 4 AM, according to police records. He said that he saw two older men standing by the mailbox in front of the building and a younger man leaning against the barbershop, which was on the first floor of the building just to the right of the alcove, the records say.

The cab driver said that the younger man — who he would later identify as Carver — was in his mid-twenties, was about five feet and 11 inches tall, had dirty black hair and a growth of beard, and was wearing dark clothes, including a T-shirt with white lettering that possibly said “Make it in Massachusetts,” the records say.

But about a week after Carver provided police with the clothing he said he was wearing the morning of the fire, which included a pair of denim overalls, the cab driver met with investigators again, police records show. The cab driver “stated that the reason he could not see all of the [person’s] shirt was because the subject appeared to be wearing bib style pants or like [sic] coveralls,” the records say.

The cab driver also initially told the police he saw a green car and a blue car parked in front of a construction site next to the Elliott Chambers, police records say. The records do not say that the cab driver described the make or model of either car or mentioned any distinctive details about them.

But police, who knew that Carver drove a Cougar, interviewed the cab driver again and he said that the blue car was either a Cougar or Ford Torino, police records say.

Police brought the cab driver to the Beverly Hospital parking lot, where they knew Carver’s Cougar was located at the time, according to police records. The cab driver pointed out the car but said the color was lighter than the one he saw on July 4, 1984, the records say. A State Police investigator asked the cab driver whether the color difference could be explained by the lighting conditions outside the Elliott Chambers, which the driver said was possible, the records say.

The investigator’s question was “a form of steering and positive feedback that could have influenced both [the cab driver]’s inclination to identify and his confidence in the identification,” according to Franklin’s report.

The cab driver also testified that the blue car he saw on July 4 had two features that other witnesses said Carver’s Cougar had: damage to the front grill and mag wheels, which are distinctive spoked wheels popular with car enthusiasts.

“The only reason I noticed the car was I noticed it had mag wheels on it,” the cab driver testified.

However, the State Police investigator testified that the cab driver didn’t mention mag wheels or grill damage until 1987, about three years after the fire.

Between August 1984 and April 1988, law enforcement showed the cab driver the same photo array three times and then showed him an in-person lineup.

The repeated identification procedures were problematic, according to Franklin, because of the so-called “mugshot-exposure effect.” When witnesses are shown the same face multiple times, they develop a sense of familiarity that can lead them to falsely identify people, she writes. Witnesses should not be subjected to more than one identification procedure per suspect, she writes, and only the results of the first procedure should be used as evidence.

The first photo array was conducted by the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department because the cab driver lived in California at the time. The cab driver viewed headshots of nine white men from Massachusetts, one of whom was Carver. Eventually, the cab driver picked a photo, according to police records.

It depicted a totally different man, the records say.

The man the cab driver selected was not a suspect — he was a “filler,” a person who bears some resemblance to the suspect and is included in a photo array or lineup to avoid steering the witness to a specific person.

At some point after that, the cab driver picked Carver’s photo too and said, “It’s one of these two here,” according to the records.

The cab driver recalled spending about 20 minutes looking over the photos before he picked the two, according to his April 1988 grand jury testimony.

However, “an ID decision based on actual face recognition typically takes seconds,” with some research showing that identifications made after 30 seconds have a more than 80 percent chance of being incorrect, Franklin writes.

During the second photo array, the cab driver picked out the photos of Carver and the filler and then said that Carver was the person he saw on July 4, according to police records. During the third array, the cab driver picked out both photos and “said that he had trouble with these two photographs in the California array,” the records say. He then selected the filler as the person he saw, the records say.

When testifying, the cab driver said he selected Carver all three times. He said that he kept taking out the filler’s photo only to demonstrate the appearance of Carver’s hair on July 4.

When investigators conducted a lineup at the Danvers Police Station in April 1988, nearly four years after the fire, they included Carver but not the filler, according to police records.

Weiner, the prosecutor, gave the cab driver written instructions that told him he should try to identify “the man [he] saw standing outside of the Elliott Chambers … wearing bib overalls,” records show.

The mention of overalls is “concerning,” Franklin writes, because it “would constitute suggestive positive feedback or apparent corroboration of that memory.”

The cab driver selected Carver from the lineup and said, “I think that looks like the guy,” according to police records. The cab driver asked Carver to step forward, and then said, “That’s him,” the records say. After the lineup, the cab driver commented “that he could never forget that guy’s lips,” the records say.

According to Franklin, identification procedures are much more reliable when conducted by “blind” administrators — people who don’t know which person is the suspect.

“In the lab, studies have demonstrated a remarkable number of ways that people playing the role of ID administrators can verbally and/or non-verbally steer witnesses toward the suspect, even if they have been instructed to avoid doing so and even without being aware of doing so,” Franklin writes.

However, the second and third photo arrays and the lineup were conducted by investigators from Massachusetts who knew Carver was the suspect, police records show. It’s unclear whether the California deputy who conducted the first array knew Carver was the suspect because he did not say in his report nor did he testify.

But even before police used suggestive comments and identification procedures, the cab driver was already a problematic witness, according to Franklin. It’s unlikely that the driver could have remembered all the details he initially reported to police, or even observed all those details in the first place, she writes.

The cab driver was in a car and his “view of the man in the doorway was brief and from a substantial distance, under nighttime lighting conditions,” according to Franklin.

The dark area was lit by streetlights and storefront signs; these “point sources” of light only illuminate people and objects from one direction and therefore “create shadows, distorting shape perception and increasing [identification] errors,” Franklin writes.

As the cab driver passed the building, his view of the man by the alcove would have been partially obstructed by the two older men who were closer to the street, according to Franklin. The driver’s attention would also have been divided among the three men, the two cars, and the road he was navigating, Franklin adds.

“Interestingly, [the cab driver] still expressed uncertainty in his identification [during the lineup],” Franklin writes. “He requested that Carver step closer, despite his one view of the man in the alcove having been from a longer distance and under poorer lighting, and despite having implied that he noted the man’s distinctive lips from that distance.”

Semel argues that Franklin’s findings do not entitle Carver to a new trial because Jackson was able to effectively question the reliability of the cab driver’s testimony without the benefit of post-1989 research on eyewitness memory.

Semel also argues that Franklin’s testimony about the unreliability of eyewitness testimony would be a “double-edged sword” for Carver. Jackson, she notes, used testimony from two newspaper delivery drivers to argue that Carver was not the person the cab driver saw. The delivery drivers, one of whom delivered the newspaper bundle to Davis Drug, also testified that they saw someone outside the building shortly before the fire, However, neither of them identified Carver.

Franklin writes that research shows the delivery drivers’ testimony would still be valuable for Carver’s mistaken-identification defense. The delivery drivers, she notes, did not identify Carver after being subjected to a suggestive identification procedure and even after investigators had them hypnotized in an unsuccessful effort to elicit more information.

Kavanaugh and Whitmore also argue that, if current research was available during Carver’s trial, Jackson could have asked the judge to exclude the cab driver’s in-court identification of Carver. Then there would have been no need to counter the cab driver’s testimony with other witnesses, they write.

“I Don’t Believe It Affected Any of My Trials”

Carver’s new attorneys are also questioning whether Jackson should have been representing Carver at all. Records uncovered by The Dump and provided to Kavanaugh and Whitmore reveal the shocking extent of Jackson’s drug and alcohol problem and other misconduct at the time he was representing Carver and other clients.

On the afternoon of June 6, 1989, two-and-a-half months after Carver’s first trial ended, Jackson had just left Peabody District Court.

He was driving his white Porsche down Lynn Street in Peabody when he fell asleep and his vehicle veered off the road, struck a fire hydrant, a utility pole, and two gas pumps before finally flipping onto its roof and catching fire, according to accounts in The Beverly Times and The Salem Evening News.

A bystander pulled Jackson from the burning vehicle, according to the news reports.

Prosecutors filed OUI charges against Jackson, which hung over his head throughout Carver’s second trial. The dramatic crash also helped put Jackson on the radar of a state board that would uncover a drug and alcohol problem that went far beyond one accident.

In March 1990, a few months after Carver was sentenced to life in prison, Jackson too was sentenced to spend time behind bars.

Jackson pleaded guilty to driving under the influence of drugs after a prosecutor from the Massachusetts Attorney General’s Office alleged a test showed traces of cocaine in his blood and court personnel observed him to be “incoherent,” “mumbling,” and “having difficulty with his speech” shortly before the crash, according to reporting by The Beverly Times and The Salem Evening News.

Jackson was sentenced to spend 30 days of a two-year sentence in jail followed by two years of probation, according to court records. The crash was also one of several factors that led the Office of Bar Counsel, the state entity responsible for investigating and prosecuting attorney misconduct cases, to file a complaint against Jackson in 1991.

Complaints against attorneys are reviewed by the Board of Bar Overseers (BBO), a separate state entity that decides whether to impose disciplinary action. The BBO held two hearings related to Jackson, one in November 1991 and a second in February 1992. The records from those proceedings were not made public until three decades later, when The Dump asked the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court to pull them from its archive.

The BBO found that Jackson failed to return thousands of dollars in unearned fees to three former clients in criminal cases, neglected a civil case which led to a costly default judgment against another client, and had inappropriate interactions with two teenage girls. Jackson also failed to comply with a subpoena to testify at the first hearing, which required it to be rescheduled, the BBO found.

Jackson’s own brief to the BBO said that his “disciplinary violations were a direct result of such an extreme substance abuse and alcohol problem that it was nearly impossible for [him] to employ rational behavior in the absence of rational thinking.”

And Jackson’s testimony and medical records make it clear that his substance-use problem took place while he represented Carver.

Kavanaugh and Whitmore argue Jackson’s blunt admission that he couldn’t think or act rationally “underscores that it was impossible for [him] to effectively represent Mr. Carver.” They write that, when determining whether Jackson was a competent attorney, the court must evaluate his decisions “against the backdrop of [his] personal and professional status at the time of trial.”

Robert Warner, the Bar Counsel attorney who prosecuted the misconduct case, told the BBO that he found it “frightening … to think of Mr. Jackson [being] involved in serious felony representation,” according to transcripts of the proceedings.

“Mr. Jackson has deep-seated problems with no insight into them whatsoever,” Warner said. “To allow him to continue practicing law under the present circumstances is just inappropriate. It’s not protecting the public.”

Even Jackson’s own lawyer told the BBO that he shouldn’t be handling murder cases at that time because of his personal struggles.

In 1992, the BBO unanimously voted to suspend Jackson’s law license indefinitely. A justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court later reduced the suspension to three years.

When testifying to the BBO, Jackson was adamant that he hoped to continue representing clients in serious cases.

“At one point I had six or seven murder cases, five or six rapes and I was going nonstop,” he testified. “I can’t imagine me practicing law and not doing those types of things because that’s what I like to do. … Maybe the workload, but I don’t think I should be stopped from practicing, doing murder cases.”

However, Jackson never got back his law license, according to BBO records.

Jackson said that he developed a problem with alcohol while attending college in the early or mid ’70s and began using cocaine in 1983 while bartending, according to medical records introduced at the BBO hearing.

After leaving his job at the Essex County District Attorney’s Office, Jackson started a job at a private law firm around January 1984 and began defending clients in criminal cases. He testified that his supervisor at the firm would ask him whether he was using drugs but he would deny it.

Jackson testified that his “cocaine problem was at [its] worst” in the summer of 1988, after his fiancee broke up with him because of his cocaine use. It was also shortly after April 1988, when he had taken on Carver as a client — a period during which he needed to investigate the complex case and prepare for trial.

Jackson said he was spending $500 a week on cocaine at the time, according to medical records.

He testified that he attended parties, used cocaine with other people, and eventually started calling “party lines,” pay-by-the-minute services that allowed callers to converse with groups of strangers.

“I didn’t sleep,” he said. “[I]t was a way to stay up all night talking to someone and to pass the time.”

He testified that the lengthy calls caused his phone bills to grow to more than $1,000 per month.

“I don’t believe [my drug use] affected any of my trials up to that point,” he said. “It was affecting me wanting to get up in the morning. … So I would stay home basically, get up late, and I would be telling [my employer] I was … doing work at home.”

He added: “I found myself not being able to sit still at meetings, sweating a lot, being late, rescheduling appointments.”

Jackson’s private investigator testified that he spoke with the attorney about his alcohol and cocaine problem on multiple occasions, possibly including during one of Carver’s trials.

“I saw the case load he was doing and the circuits were overloaded,” the investigator said. “I just saw this guy under a tremendous amount of stress.”

In October 1988, Jackson admitted himself to the Edgehill Newport Hospital for an addiction-treatment program after a conversation with his supervisor at the law firm, he testified. He left the hospital after 17 days, before completing the program, he said, then he parted ways with the firm in what he described as a “mutual agreement.”

He testified that he stopped using cocaine after leaving Edgehill but relapsed in April or May 1989, shortly before the car accident.

Jackson’s psychiatrist attributed the relapse to pressure from work, testifying that the attorney said he had been involved “in a tough case and had started slipping back.”

The psychiatrist did not specify the case, but Kavanaugh and Whitmore say they believe he was referring to the Carver case.

Jackson testified that “things were going very well” at that time and that work-related pressure played no role in the relapse.

“I left [Edgehill] with that belief that I could still go out and have a couple of drinks without doing cocaine,” he said. “And I did that for a while until finally in April it obviously caught up with me and I did do coke again.”

He testified that he stopped using cocaine within a week after the June 1989 accident but continued drinking. He said that he hadn’t “been drunk” since the accident and last had alcohol four or five months before the 1991 hearing, saying he had “some wine” at a function.

But Kavanaugh and Whitmore have raised suspicion about an incident during Carver’s second trial when Jackson failed to show up for court without warning.

Jackson’s private investigator told the court in November 1989 that the attorney was in his hotel room vomiting. After speaking with Jackson again, the investigator added, “He says he’s hot, cold, shivering, and he has the dry heaves now and he is running to the bathroom.”

When Judge Mathers asked Weiner what he wanted to do, the prosecutor responded with a cryptic comment.

“I would like to see a doctor’s note at this point,” he said.

The comment shows that Weiner “had reason to doubt the sincerity of Jackson’s illness,” Kavanaugh and Whitmore allege.

“No Sex Occurred At Any Time”

In 1998, Carver’s former post-conviction attorney, Dana Curhan, brought an explosive allegation to court. Carver’s ex-wife, who was married to him throughout his two trials, said in an affidavit she signed two years earlier that she had a sexual relationship with Jackson while he represented Carver.

Curhan argued that the allegations entitled Carver to a new trial regardless of how well Jackson performed in the courtroom because the alleged sexual relationship created a conflict of interest, according to court records.

“Specifically, if counsel performed diligently and secured an acquittal for his client, his relationship with [Carver’s wife] would likely end; if, on the other hand, counsel performed poorly and the defendant were convicted, trial counsel would be free to continue his wholly inappropriate relationship,” Curhan wrote.

Essex County Superior Court Judge Nancy Merrick held a hearing about the allegations in December 1998. Curhan presented testimony from the ex-wife, and Weiner argued that her allegations weren’t credible and weren’t a good enough reason to overturn Carver’s conviction.

The ex-wife testified that she wanted to get information about Carver’s case and Jackson invited her to his condo in Salem. When she arrived, Jackson gave her a glass of wine, then they went to the living room and watched pornographic videos while he masturbated, she said.

At some point, Jackson asked her to go upstairs, where he gave her some Victoria’s Secret clothes to wear and asked her to walk around the room in them, she said. Jackson then asked her to sit on the bed and perform oral sex on him, which she did, she said.

“He wanted more and I said no,” she said. “I said I don’t want to do this anymore.”

After the alleged encounter, Jackson would call her “almost every night” and he would masturbate during the calls “pretty much all the time,” she said.

However, she said that she couldn’t remember when the alleged visit happened. She also said that she could not remember two earlier visits to Jackson’s condo during which he allegedly showed her pornography and masturbated, which she had described in her 1996 affidavit.

Weiner argued that there was no evidence the alleged sexual relationship affected Jackson’s ability to impartially represent Carver. And, the prosecutor argued, speculating that the alleged relationship hurt Jackson’s performance would be no different than speculating that it helped.

“Maybe this relationship, if it were true, would have spurred [Jackson] on to do better work,” Weiner said. “Maybe he thought this was part of his payment. We don’t know, … [a]nd the cases say you can’t speculate in deciding this kind of a motion.”

Curhan argued that the ex-wife’s inability to remember certain details was to be expected since the events took place nine years prior to her testifying.

Prior to the hearing, Jackson told police that the ex-wife visited his condo in Salem twice and that they spoke on the phone “a lot,” according to police records. He said he thought the visits occurred after Carver’s second trial but that he wasn’t sure, the records say.

“No sex occurred at any time,” he told police, according to the records.

Judge Merrick ruled against Carver in February 1999, writing that she found the ex-wife’s testimony “vague, confusing and contradictory.” Merrick also wrote that the ex-wife’s testimony might have been influenced by a custody battle over her and Carver’s daughter.

Carver’s parents had temporary guardianship of the daughter at the time of the hearing. Merrick wrote that the ex-wife’s “demeanor while on the witness stand included frequent, nervous glances toward [Carver]’s parents.”

But Kavanaugh and Whitmore say there is other evidence that lends credibility to the ex-wife’s testimony. They point to records documenting numerous harassment allegations against Jackson by teen girls — along with criminal charges filed against him in 1998, shortly before the December hearing. Neither the criminal charges nor the earlier harassment allegations, some of which were described in the BBO records, were presented to Merrick.

The combined impact of the conflict of interest created by Jackson’s alleged sexual relationship, his overall poor judgment, and the new scientific evidence about fires and eyewitness testimony “clearly creates a substantial risk of a miscarriage of justice,” Kavanaugh and Whitmore write.

A few weeks after Carver’s first trial, police began investigating allegations that a man identifying himself as “Paul Kelly” called a number of teen girls, according to police records. The girls said that “Kelly” claimed to be an amateur photographer who wanted them to model for him so he could complete his portfolio and asked them for the names of friends who might also be interested in modeling, the records say.

In total, police spoke with five teen girls who said they were called by “Paul Kelly,” the records say. Two of those girls were deposed in the BBO case against Jackson.

A 16-year-old who received one of the calls from “Kelly” met him at a food market in Salem, she testified in a deposition. The man showed her a photo ID, revealing his real name as Dennis Jackson, and asked her to come back to his condo behind the market, she said. She agreed, he drove her there, and he then went upstairs and retrieved a newspaper that included a photo of him with someone named Carver, she said.

“After we got back to the house, he wasn’t talking about modeling anymore, … just we should go out, we should go to dinner, get to know each other,” she said.

Jackson offered her a drink, but she declined, saying she had to work, she said. He suggested that she take the day off to spend time with him and drove her back to the parking lot outside the market, she said.

Jackson, in his BBO testimony, acknowledged meeting the girl, taking her to his condo, and discussing the Carver case with her.

However, he said that he first spoke with her on a party line. He said that she was the one who brought up modeling and that he told her his friend was an amateur photographer who took pictures of fully clothed models.

He denied using the name “Paul Kelly” and said that he did use an alias at first but couldn’t remember what it was. He also said that he didn’t know the girl’s age but thought she was 18 or 19.

The other girl who was deposed in the BBO case testified that a caller who identified himself as “Paul Kelly” contacted her when she was 16. The man asked whether she had ever used marijuana or cocaine, asked whether she had oral sex, and said that if she didn’t enjoy sex it was because it wasn’t with an older, experienced person, she said.

Jackson, in his testimony, denied knowing who the girl was.

A 17-year-old girl who told police she received calls from someone who identified himself as “Paul Kelly” was the younger sister of a defense witness in the Carver case, according to police records. She said that during one of the calls, she heard the man breathing heavily and she thought she heard him say “You make me eel [sic] so good,” the records say.

The girl did not testify to the BBO, and Jackson was not asked about her when he testified.

Police did not bring charges against Jackson for these calls or his in-person meeting with the 16-year-old.

But on June 5, 1998 — six months before Carver’s ex-wife testified — Barnstable police arrested Jackson for allegedly making a series of similar harassing phone calls to other women and girls in Barnstable and Falmouth, according to police records. Police obtained a warrant after Jackson’s name and number showed up on caller ID boxes at some of the residences he contacted, the records allege.

Prosecutors charged Jackson with eight counts each of making annoying telephone calls and accosting or annoying a person of the opposite sex, according to court records.

In June 1999, Jackson received pretrial probation, and the charges were dismissed the following year, court records say.

“It’s Just Like My Cancer”

Once James Carver’s upcoming hearing ends, the wait will begin for him and his attorneys as Judge Karp mulls over whether to overturn his conviction.

Julie Nickerson Benedix hopes the judge won’t release Carver from prison. She lost three family members to the fire, her brothers Rick and Ralph Nickerson and her grandmother Hattie Whary — and she believes Carver is responsible for their deaths.

“They died when I was 14, and they were buried on my 15th birthday,” she told The Dump. “I’m going on 55 years old. My life has never been the same, and I don’t have birthdays nor do I want them. Celebrating just isn’t an option.”

Her parents have also died in the nearly 40 years since the fire. Her father passed away in 2019 and her mother in March.

“My whole family I grew up with is gone,” Benedix said. “I am the only one left. … Why should [Carver] be out living his life when he stole so many lives and tore families apart?”

She said Carver was a “sick” and “seriously warped” person who killed out of jealousy.

“He wouldn’t have been in [prison] this long or convicted if he was innocent,” she said. “He’s evil in true form.”

If Karp sides with Carver, his ordeal might still not be over. Prosecutors could appeal. And they could put him on trial for a third time — although it would be difficult now that many witnesses have died and the living ones’ memories have faded.

In any event, the hearing will not be Carver’s first time before Karp.

Carver became eligible for traditional parole in September 2018 but “has waived his right to parole hearings … because he simply cannot accept responsibility for a crime he did not commit,” Kavanaugh and Whitmore write.

However, Carver sought compassionate release from prison under the state’s medical parole law in 2020, according to court records.

The Massachusetts Department of Correction — with the support of the district attorney’s office — denied Carver’s request later that year and again in 2021, saying he was not debilitated enough to be eligible and was too dangerous to be released.

Carver, with the help of another attorney, took the Department of Correction to court. But Karp declined to overturn the agency’s decision in a December 2021 ruling.

Carver has had epilepsy since he was young but has developed many other health problems during his decades in prison, according to court records.

He had surgery to remove a brain tumor in 2005 and as a result is incontinent, has difficulty standing, and requires a wheelchair to get around, court records say. He experiences tremors, requires assistance getting dressed and eating when they occur, and he is deaf in one ear and hard of hearing in the other, the records say.

“When The Salem News shows any story of him, they show a picture of a [young] man,” said Bill Carver, the brother. “He is now a 60-year-old man. … He’s no threat to anybody anywhere.”

As part of James Carver’s rejected medical-parole plan, he proposed living with his daughter.

His daughter is now married and has three children of her own, Bill Carver said. He said his brother and niece have had a “fantastic relationship” but that it “certainly [would have been] better if he was home to do all the regular stuff that dads will do with their daughters.”

“It was really hard on him,” Bill Carver said. “But it was also hard on her.”

He said he’d like to attend his brother’s hearing, but he’s undergoing treatment for stage-four kidney cancer and can’t make the trip from Michigan where he now lives.

However, he said he believes he has many years of life left and his Catholic faith keeps him from worrying too much.

“When God takes me, that’s when God takes me,” he said. “It’s not that I don’t care. It’s just that I have confidence that if I do pass on not [being] able to see [my brother] from here in this world, I’ll see him in the next.”

But, he said, his brother is anxious about the hearing and what his life will be like if he is released from prison.

“The outcome is unknown,” he said. “It’s just like my cancer.”

CORRECTIONS: This piece has been corrected to say that Nancy Franklin discussed the “mugshot-exposure effect,” not the “mugshot effect.” It has also been corrected to say that Carver “had been under investigation for months,” not years, in October 1984. It has also been corrected to say that Dennis Jackson started his job at a private law firm in 1984, not 1983.

Thank you so much for making it through this huge story. It took me more than a year and a half to put it together — and as long as it is, there’s much more to say in the future. I’ll be writing a follow-up story at some point after the hearing and another after Judge Karp makes his ruling.

Again, if you’d like to keep The Mass Dump running, please consider offering your financial support, either by signing up for a paid subscription to this newsletter below, becoming a Patreon supporter, or sending a tip via PayPal or Venmo. It takes a tremendous amount of work to bring you stories like this, and I rely on your support to keep doing it.

Even if you can’t afford a paid sub, please sign up for a free one to get updates about this story, and please share this story on social media.

If you have any information about the Elliott Chambers fire or the James Carver case, please email me at aquemere0@gmail.com.

A Parting Thought...

If you visit the corner of Rantoul and Elliott in Beverly now, you won’t find the Elliott Chambers Rooming House. Instead, you’ll find a CVS filling in for the now-defunct Davis Drug. But you’ll still see evidence that something horrible took place there once upon a time.

A modest hunk of polished granite rests between two benches. Affixed to it is a bronze plaque engraved with the names and ages of the 15 people who were killed by the fire. The monument was donated by the Elliott Chambers Fire Memorial Foundation in 2010.

I first visited this spot during one of my many research trips to the Beverly Public Library. To me, the size of the monument seems to understate the magnitude of what happened there nearly 40 years ago — and the way those events still impact us today. But perhaps it would be unreasonable to expect something bigger. It’s a commercial space, and business must go on. The monument’s subtlety is a reminder that we often move about the world oblivious that it is haunted by the ghosts of countless tragedies past.

The Elliott Chambers fire — whether it was an accident or the “worst mass murder in Massachusetts history” — was no doubt a tragedy. And we owe it to the ghosts, and the living, to learn its lessons.

Really fantastic work on this!