Expert Witnesses Debate Cause of Deadly Fire That Led to Man’s Life Sentence

James Carver was sentenced to life in prison for a fire that killed 15 people — but decades later, that fire’s cause is up for debate

In July 1984, fire tore through the Elliott Chambers Rooming House in Beverly, killing 15 people — and law enforcement blamed the blaze on a young man named James Carver, who a jury would convict of arson and murder five years later.

But for the past 34 years, Carver has maintained his innocence while serving two consecutive life sentences in state prison. And this past April, the cause of the horrific fire was contested in court, with a retired fire-safety engineer testifying that the prosecutor’s theory of how the blaze started was wrong. At the same time, a retired Massachusetts state trooper defended the prosecutor’s theory despite acknowledging it was based in part on scientifically invalid testimony.

Carver’s lawyers say the new testimony, which was delivered during the first three days of a five-day hearing in April and May, shows that Carver was wrongfully convicted and is entitled to a new trial.

In Massachusetts, a judge “may grant a new trial at any time if it appears that justice may not have been done,” according to the state’s rules of criminal procedure. Lawyers must either present important evidence that was not available at the time of the original trial or show that the defendant’s trial lawyer was unusually ineffective.

During the 1989 trial, a prosecutor for the Essex County District Attorney’s Office argued that Carver started the fire by pouring gasoline on a bundle of newspapers and burning it in the rooming house’s entrance because he was angry his ex-fiancee dated a man who lived in the building. An arson investigator testified that he observed charring on the walls outside the doorway that could have only been caused by a fire started with a flammable liquid like gasoline.

However, Carver’s lawyers said at the hearing that developments in fire science have discredited the investigator’s testimony and that the fire might not have been caused by arson.

During April 9 through 11, Carver’s lawyers presented testimony from engineer Craig Beyler, who is technical director emeritus at the consulting company Jensen Hughs. Beyler reviewed reports, witness statements, trial transcripts, and photos related to the Elliott Chambers fire and prepared a report with his findings before the hearing.

Beyler said it was physically impossible for the newspapers to have generated a flame powerful enough to have spread to the building. He said the fire’s true cause can’t be determined based on the available evidence and that he could not rule out accidental causes like an electrical malfunction.

Beyler said the investigator’s conclusion that the blaze was started using a flammable liquid was based on myths about fire that were commonly cited in the ’80s but have since been debunked by scientists.

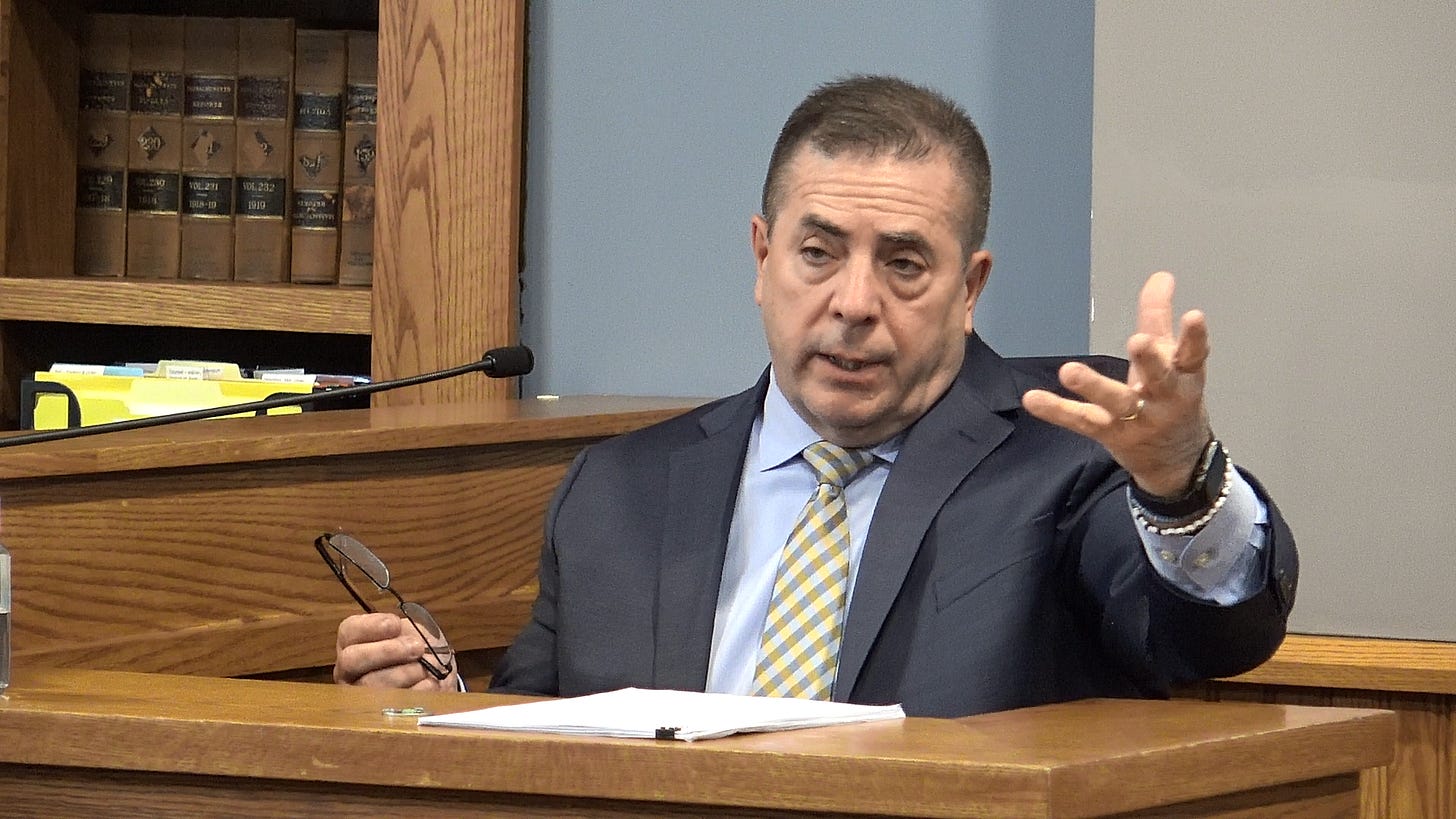

The district attorney’s office presented its own expert witness, Michael Mazza, a retired Massachusetts State Police fire investigator who now works for the Massachusetts Department of Fire Services and the Connecticut-based company Acacia Investigations. Mazza was not involved in the original investigation of the Elliott Chambers fire, but he reviewed the same materials as Beyler and prepared a report before the hearing.

Mazza agreed with Beyler that there was no physical evidence a flammable liquid was used but said he agreed with the investigator’s conclusion that the fire was started by burning the newspapers outside the entrance.

A spokesperson for the district attorney’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

Carver, who is now 60, has difficulty standing and requires a wheelchair to get around due to a 2005 surgery to remove a brain tumor, according to court documents.

Each day of the hearing, he was placed in a wheelchair van at Old Colony Correctional Center in Bridgewater, driven about 70 miles to the courthouse in Lawrence, and then wheeled to the defense table by a court officer. He listened to the testimony with headphones because he is hard of hearing.

Carver’s wrists and ankles were shackled throughout the proceedings. On the second day, one of his attorneys, Lisa Kavanaugh, asked that the handcuffs be removed.

Essex County Superior Court Judge Jeffrey Karp said that Carver needed to remain handcuffed due to Massachusetts Department of Correction policy.

“Mr. Carver is far from an escape risk, but that’s what the policy is,” Karp said.

Carver’s daughter Kaitlyn, who was born less than two months before he was arrested, attended the third day of the hearing. She declined to be interviewed but said she hadn’t seen her father in person for almost six years.

As Carver was wheeled into the courtroom that morning, he spotted her sitting in the gallery, then his neutral expression instantly changed to an open-mouth smile, and she smiled back. The court officers allowed the two to speak briefly at the beginning of the day’s lunch break.

Carver has been represented by Kavanaugh and another attorney, Charlotte Whitmore, since 2019.

Kavanaugh is the director of the innocence program at the state’s public defender office, the Massachusetts Committee for Public Counsel Services. Whitmore is a staff attorney at the Boston College Innocence Program.

The lawyers’ March 2022 motion for a new trial is Carver’s fifth attempt at overturning his conviction. However, it is the first attempt by his current legal team — and the first attempt to use scientific evidence to challenge the prosecution’s theory that the fire was arson.

“Mr. Carver has spent nearly 40 years in prison for a fire that he did not set,” Whitmore said during a brief opening statement.

Whitmore said that Beyler’s testimony is new evidence because it’s based on scientific ideas that were not understood in the ’80s and that it “would have been a real factor in the jury’s deliberations.”

“The Commonwealth used [the] purported scientific evidence of [liquid] accelerant to prove to the jury that the fire was arson,” she said. “The Commonwealth and its fire expert now concede that the scientific evidence they used at trial to prove accelerant use is invalid.”

Lawyers for the district attorney’s office did not make an opening statement.

Investigative journalism like this takes a ton of time, energy, and care. Please consider signing up for a paid subscription to The Mass Dump newsletter below, becoming a Patreon supporter, or sending a tip via PayPal or Venmo to make more work like this possible.

“This is a Significant Discrepancy”

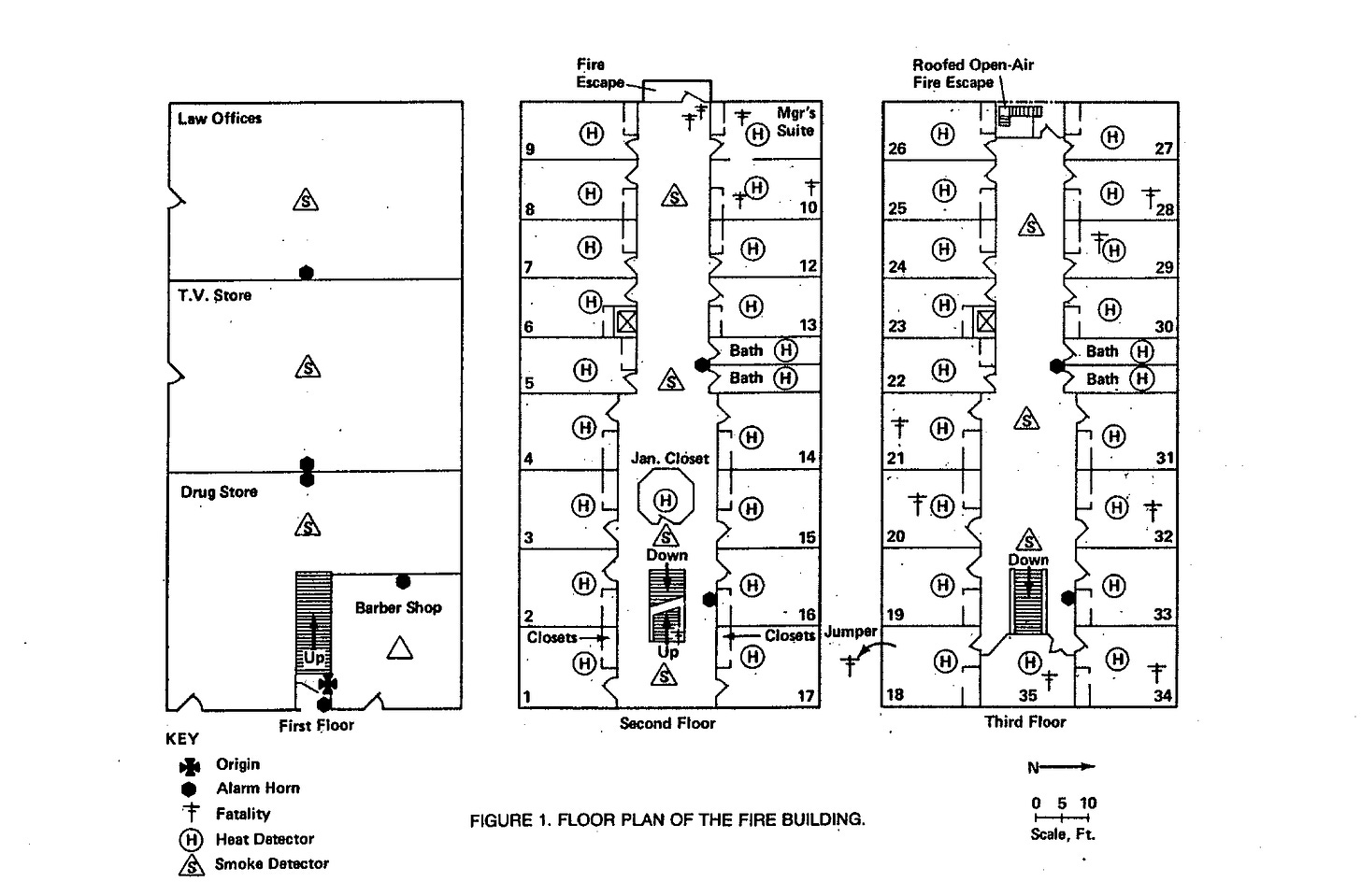

The Elliott Chambers was a three-story, wood-frame building located at the corner of Rantoul and Elliott in Beverly. The first floor contained the Davis Drug pharmacy, a barbershop, a TV repair shop, and a law office. The two upper floors functioned as a rooming house where 36 people lived at the time of the fire.

The fire broke out during the early hours of July 4, 1984. A Beverly police officer spotted flames from a half-mile away and radioed the police station at 4:18 AM. When the officer arrived moments later, he saw “flames shooting out from the front entrance” and “billowing straight up to the second and third floors,” according to his written report.

Despite the efforts of first responders, 14 people died that morning and a fifteenth victim died in a hospital a month later.

Immediately after the blaze, the Elliott Chambers was examined by a Massachusetts state trooper who was assisted by a state electrical inspector. A few days later, a fire investigator from Nassau County in New York looked at the building.

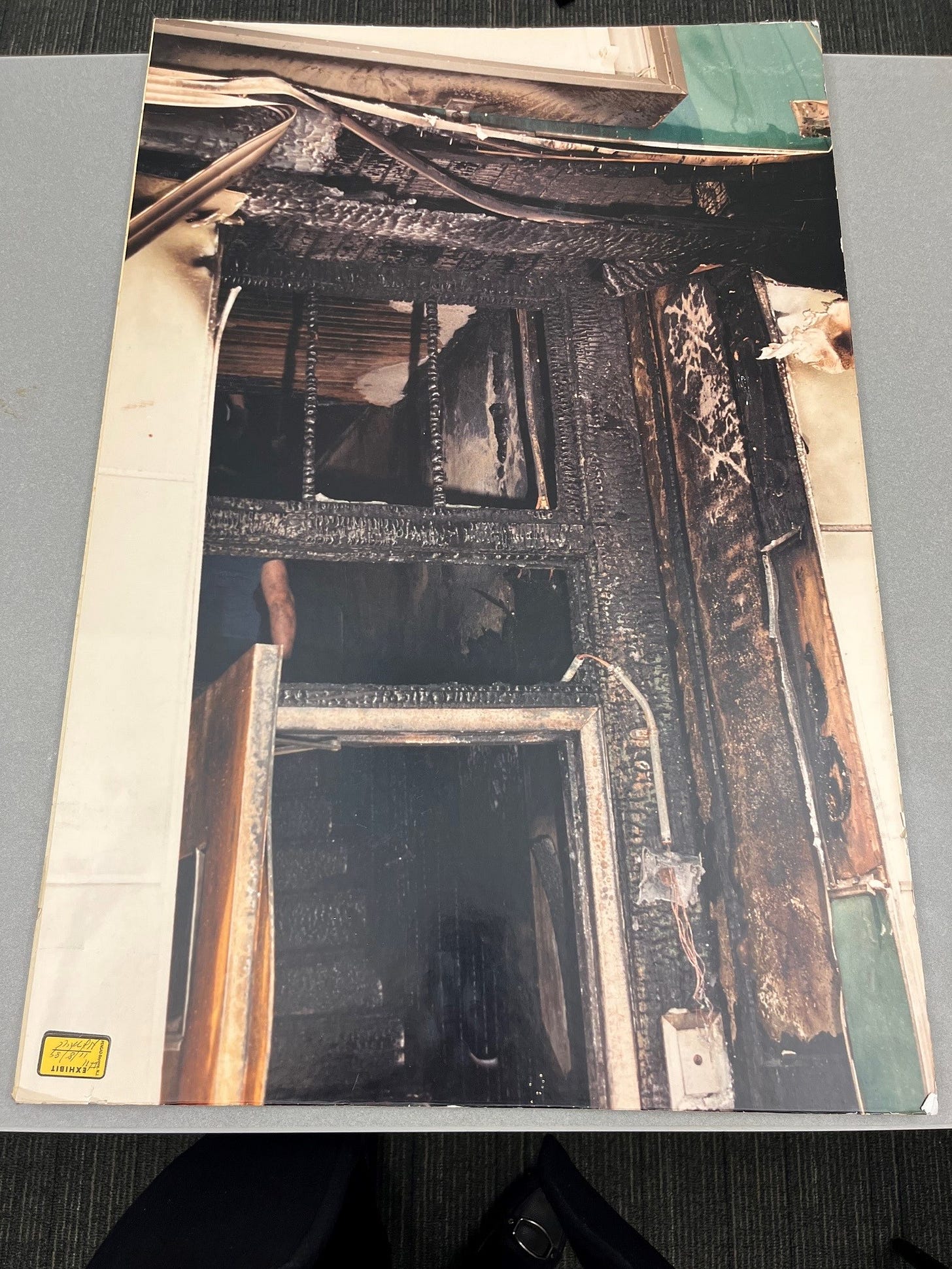

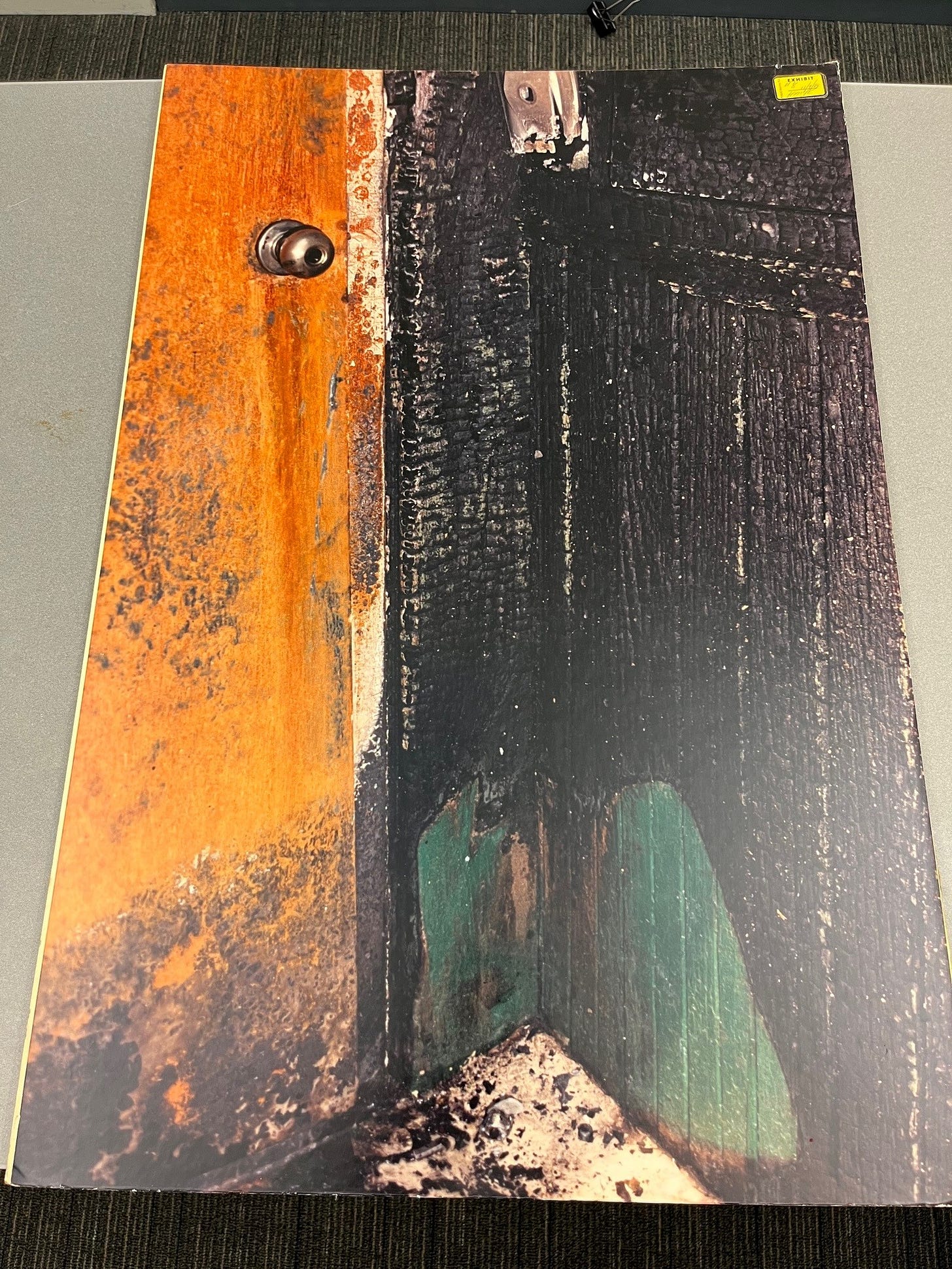

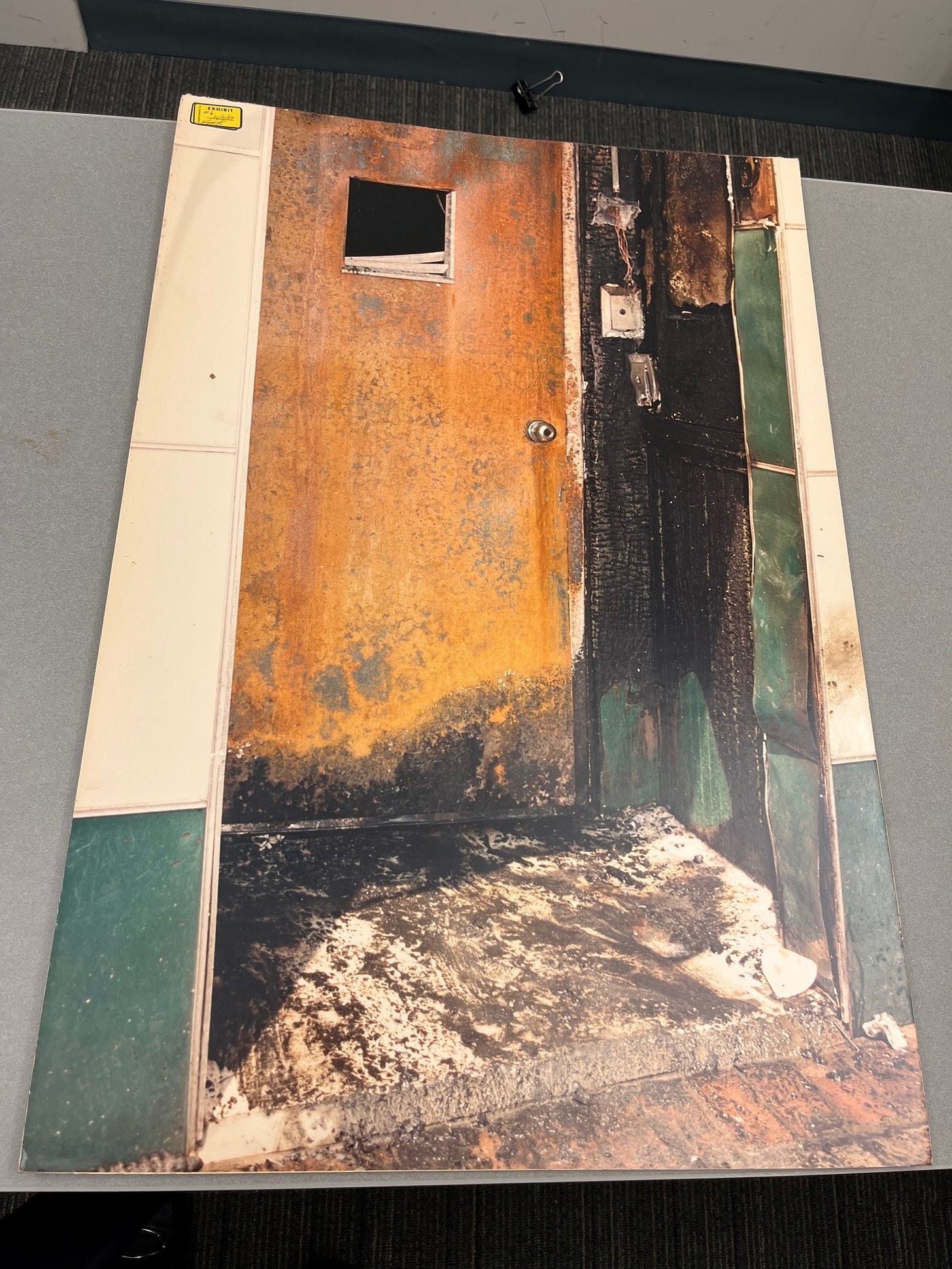

The state trooper and New York investigator both determined that the fire was caused by someone burning a newspaper bundle in the alcove that contained the entrance to the rooming house’s stairway. The flames then traveled up the walls of the alcove, broke the glass transom above the door, and were sucked through the transom into the open stairway, allowing fire to spread through the two upper floors, they both concluded.

The New York investigator, Robert Doran, also concluded that the fire must have been set using a flammable liquid like gasoline. Doran, who is now deceased, was the only fire investigator to testify at Carver’s trial.

When trying to determine where the fire started, Doran testified, he first looked for the lowest point of burn because “fire will not burn down.” He said that the lowest point of burn was in the alcove.

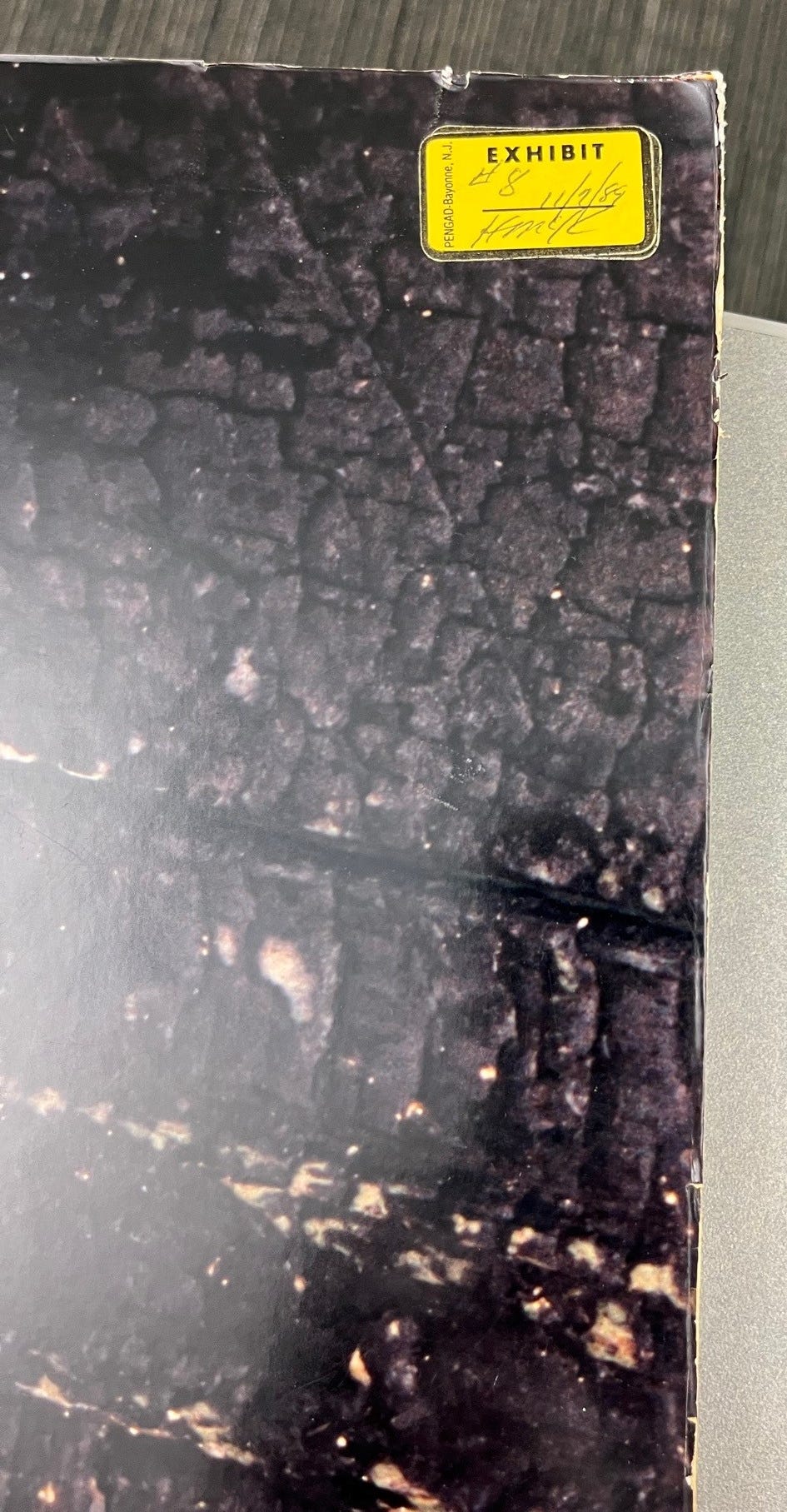

Doran said that he observed “alligator charring” blisters — which are named after their resemblance to scaly skin — on the walls of the alcove. He said that higher temperatures cause larger alligator marks and that the blisters grow deeper the longer the fire burns. The blisters in the alcove were “fairly large,” he said, “which indicated a high temperature,” but they had “no depth of char.”

Doran testified that a fire could only reach such a high temperature in a short period of time if it had been started with a flammable liquid.

A state chemist could not find any traces of flammable liquids on samples of the newspapers, the concrete floor of the alcove, or wood from the alcove. But Doran testified that this made no difference in his opinion because the flammable liquid would have been washed away by the water firefighters used to extinguish the blaze.

But during the hearing in April, witnesses Beyler and Mazza both testified that Doran relied on outdated myths about fire to reach his conclusions. Both witnesses said that fire can spread downward. They also agreed that alligator charring cannot be used to prove a fire was started using a flammable liquid and that the lack of positive lab-test results means there is no physical evidence of one.

“[Doran’s] final opinion doesn’t even rise to the level of the hypothesis because there is no data,” Beyler testified. “It’s mere speculation.”

Karp, the judge who presided over the hearing, listened attentively to the testimony, took notes, and often interjected with his own questions.

“It seems to me, and this is just an observation, that this is a significant discrepancy,” Karp said. “I mean, [Doran] told the jury that … there was an accelerant used. And … that’s not the case. Right?”

Mazza said it’s still possible that a flammable liquid was used but was washed away before it could be detected, as Doran had testified.

“But I would not be, today, comfortable saying that it’s an ignitable-liquid-fueled fire without either an eyewitness, an admission, a statement, or greater laboratory analysis,” Mazza said.

“That Ceiling is Completely Gone”

Beyler testified that the fire started in the alcove’s overhang, not on the newspapers or the ground. He ruled out the possibility that the fire started at ground level, he said, because the alcove’s overhang was damaged much more significantly than the walls.

Doran documented the charring on the walls as being a quarter inch deep. That damage, Beyler said, was “pretty superficial” while the damage to the overhang was “vastly larger than that.”

The damage to the walls and the newspapers could have been caused by a “drop-down fire,” which is when fire is spread by flaming debris that falls from a higher level of a structure to a lower one, he said.

The state trooper who examined the building before Doran wrote in his report that he did not find “any evidence of drop-type fire in the” alcove, but provided no further explanation.

Doran testified that he ruled out a drop-down fire because the overhang’s “ceiling area was intact for the most part,” but Beyler used a photograph to dispute this.

“What we see now is the charred window frame [above the doorway],” Beyler said. “We see charred structural members above the window frame. We even can see burned-off structural members up in that region. … There was a ceiling there [before the fire], and that ceiling is completely gone.”

“So,” he continued “it’s not at all intact and all of those missing materials are … classic candidates for drop-down.”

Beyler also testified that the newspaper bundle could not have caused a flame large enough to have spread to the wood-panel walls of the alcove.

According to Beyler, scientific testing with propane burners has shown that a four-foot-high flame in a corner will damage wooden walls but won’t spread to them. It would require an even larger flame that burned for several minutes to “give rise to fire spread and … contribute to the development of a fire,” he said.

“It’s my opinion that while you could ignite [newspapers], the flames would be rather short,” he said. “You’d be lucky if you got a one-foot flame height out of it. … When you have paper in a mass situation like a bundle, they don’t burn very well just like an individual log doesn’t burn very well.”

Beyler said that even if a flammable liquid had been applied to the newspaper bundle, it still couldn’t have caused the fire.

“[The newspapers] might slow the burning of the accelerant that was on them depending on the depth of absorption, which probably wouldn’t be very large,” he said. “And so I don’t see the newspapers as playing much [of] a role in an ignitable liquid scenario.”

Beyler also said that the twine holding the bundle together would have burned through if the newspapers had been used to start the fire.

The firefighter who discovered the newspapers testified that he thought they were still tied together when he kicked them away from the doorway while trying to get inside the building. Beyler said this testimony was further evidence the fire did not start on the papers.

While cross-examining Beyler, assistant district attorney James Gubitose suggested that the firefighter was mistaken. Gubitose showed Beyler a photograph of loose newspapers lying on the ground after the fire.

The picture shows the papers to the right of the rooming house’s entrance in a separate alcove containing the barbershop’s entrance.

Beyler said that the newspapers appeared to have been moved after the firefighter kicked them away.

One of Carver’s attorneys, Whitmore, suggested that firefighters might have damaged the newspapers before the photo of the loose papers was taken. She showed Beyler a different photo depicting water that firefighters used to extinguish the blaze gushing from the rooming house’s entrance into the street.

Beyler said that the water “certainly would [have] wet” any items in front of the door.

“Based on the Geometry”

Mazza said the newspaper-fire theory was supported by photographs showing unburned green paint in the lower-right corner of the alcove’s walls. This area, he said, was protected from the fire because the newspaper bundle was wedged in the corner.

Mazza said he was able to use the shape of the unburned area to determine that the newspaper bundle was propped up on its side rather than lying flat. He said that someone ignited the side of the bundle, which would be easier than trying to set fire to the top.

“When they were ignited, the flames spread based on the geometry of the way the newspapers were leaning against the … paint-covered wooden wall,” he said.

Mazza testified that placing a burning newspaper bundle against a wall would cause the fire to grow more intense.

“If … you put a pile of newspapers right in the center of the room where air can get all around it, believe it or not, the air will cool the fire growth, and the growth won’t be as dramatic,” he said. “You put it up against the wall, it becomes more dramatic, 30 percent times [sic] hotter, if you will.”

A newspaper fire would be even more intense, he said, if the bundle was placed in a corner rather than against a single wall.

“The heat’s … being reflected and the air entrainment is limited,” he testified.

Mazza said the fire in the Elliott Chambers alcove also grew because it was a “compartment fire,” meaning the walls and ceiling contained the heat and smoke.

“The rising heat and the smoke has nowhere to go until it banks down enough to escape, and in this case it escaped also through the transom,” he said.

Mazza said the studies about corner fires cited by Beyler were not relevant because, during the tests, there was air underneath the flames and there was no ceiling to contain the heat and smoke.

In rebuttal testimony, Beyler said some of the tests used ceilings and that it would not have made sense for him to cite compartment-fire studies because one side of the alcove was completely open, which allowed the heat and smoke to escape.

“[The] key features of a compartment fire is a fire burning and creating a hot gas layer,” Beyler said. “In this configuration, the plume goes up to the ceiling, runs across the ceiling, and goes out … without forming a hot gas layer.”

Under cross-examination by Kavanaugh, Mazza said that he did not cite any studies or conduct any tests to support his theory that the newspapers could have caused the fire.

He also acknowledged that the investigators who viewed the building did not take measurements of the unburned area in the corner to determine whether its size and shape were consistent with a newspaper bundle lying on its side.

“No Investigator Today Would Say That”

Beyler testified that it’s impossible to rule out an electrical malfunction as a cause of the fire. The investigators who viewed the building after the blaze said they found no evidence of a malfunction, but Beyler said they failed to collect evidence about wires that were hanging in the alcove.

Doran, the arson investigator who testified during Carver’s trial, said he examined these wires but found no evidence of a malfunction. If there had been an electrical short, the wiring would have heated and become brittle, Doran said, but it remained flexible when he bent it.

“No investigator today would say that,” Beyler testified.

“What he’s describing is an overload condition and of course, we build buildings with circuit protection to avoid that from happening,” Beyler continued. “The vast majority of electrical-fire initiations do not involve embrittlement of wire. They result from shorting, from loose connections, and things of that sort.”

Mazza said that he ruled out electrical causes for the fire. He said that he relied on the reports by Doran, the state trooper, and the electrical inspector, although he did not address whether he agreed with Doran’s testimony that the wires couldn’t have caused the fire because they were flexible.

The state trooper who examined the building before Doran wrote in his report that he eliminated electrical causes because he did not find any “electrical devices … at or near the floor area” of the alcove. His report does not say whether he examined the hanging wires.

The trooper was assisted by an electrical inspector, who wrote in his report that he checked the alcove, the entrance, the stairway leading up to the second floor, the service and meter equipment, and a fluorescent Davis Drug sign above the alcove.

The electrical inspector wrote that he found no evidence of malfunctions, but he did not explain what he did during his inspection. His report also does not say whether he checked the hanging wires.

“He seemed not to recognize the electrical equipment that was in the alcove,” Beyler said. “We have photographs of it. He acts like it doesn’t exist.”

Mazza said he believes the hanging wires were attached to a horn that was part of the building’s fire-alarm system. Photographs show that the wires ran through a small object, which Mazza said he thought was a metal case for the horn before the fire.

Mazza said he concluded that the alarm system was not involved in the fire. He said he relied on a report by the state trooper, who brought the alarm system’s annunciator panel to the supplier to examine. The supplier determined that there was no evidence of an electrical short, according to the trooper’s report.

“There’s multiple strands of wire that are consistent with low-voltage wiring, which would be consistent with an alarm system,” Mazza said.

Low-voltage wires aren’t a common cause of fires, he said.

“Is it impossible? I don’t think it’s impossible,” he added. “It’s very unlikely.”

In rebuttal testimony, Beyler said the voltage of the hanging wires couldn’t be determined without examining them in a lab setting. However, Beyler said, Mazza’s testimony about the wires meant that Mazza couldn’t rule them out as a possible cause.

“He’s correct that low-voltage devices can start fires,” Beyler said. “And basically by saying that it’s possible, and maybe unlikely, but possible, … [that] means basically that the fire cause has to be undetermined.”

To support his conclusion that the wires were connected to an alarm horn, Mazza used a diagram from a report by the National Fire Protection Association, which examined the Elliott Chambers in 1984 after investigators finished viewing it. The diagram shows a symbol for an alarm horn in the alcove.

However, during cross-examination by Kavanaugh, Mazza said that the symbol is located near the street, not in the corner where the wires were located. He also said that the investigators and electrical inspector did not document the location of the alarm horn or the purpose of the hanging wires.

Beyler said he did not think the wires were connected to the alarm horn. He said it was more likely that the horn was located near the street, as shown in the NFPA diagram.

That location would make more sense, he said, because “the goal of this horn is to … project sound away from the building so that people in the neighborhood have the greatest chance to recognize there’s a fire there and report it.”

“That’s Not the Scientific Method”

Beyler said it’s likely there was a light in the alcove and that it might have been attached to the portion of the overhang that was destroyed by the fire. Building entrances usually have lights so that people can see their keys when it’s dark out, he said.

It’s also possible, Beyler said, that the wiring in the alcove was connected to a light. He said that the object Mazza identified as a case for the alarm horn looked like a junction box, a casing used to protect wire connections, and that it’s common for lights to be mounted on junction boxes.

The electrical inspector said in his report that he checked the alcove’s overhead area and did not notice any lights or wiring.

However, Beyler said, there’s no documentation showing that investigators searched the debris on the ground for the remains of an overhead light or asked the building owner or surviving residents about the possibility of one.

“I can’t speak to why those things weren’t done,” he said. “But those are things that today naturally we would do.”

Mazza said there was no evidence that the fire was caused by an overhead light because investigators did not document finding one in their reports and there was no photographic evidence.

“I recognize nothing up there [on the overhang] that would be a heat source,” he said. “There’s no evidence of an electrical system or components remaining in any of the pictures.”

He said the lack of photographs showing overhead electrical devices also led him to conclude that the damage to the alcove wasn’t caused by a drop-down fire.

Beyler said it was improper for Mazza to determine the fire started on the newspapers based on his belief that there weren’t any electrical devices in the overhang.

“[A] lack of evidence is not evidence,” Beyler said. “Evaluating [the] origin or cause [of a fire] should be based on data, not the lack of data.”

Beyler said the reports on which Mazza relied “are basically summary conclusions” that are not backed up by the quality of evidence required by modern, science-based standards for investigating fires.

“You need to understand the electrical system as it existed within the area of [the fire’s] origin, which would normally include tracing wires, understanding what devices were present, going back to the panel, identifying if the circuit breaker operated or fuse [box operated],” Beyler said.

It’s not even clear whether the building had a circuit breaker or fuse box because investigators failed to document whether they looked for one, he added.

Under current standards, Beyler said, investigators are required to thoroughly document their work, which includes writing down everything they did, taking close-up photographs of all electrical devices, collecting the electrical devices, and viewing them under a microscope in a lab. None of that was done in this case, he said.

“There’s no data,” Beyler said. “There’s no data analysis. There’s no hypothesis formation. It’s just I looked, I saw, this is the answer. Now that’s not the scientific method. … And so today, we wouldn’t give it any credit. I give it no credit.”

Mazza said that he’s worked with state electrical inspectors on investigations before and they normally conduct thorough examinations.

“They would document the electrical system going into the building from the pole outside to the service meter to … either the electrical breaker box or fuse box, from there into the circuits of the building throughout and then work in the area that was of interest to [the investigator],” he said.

Under cross-examination by Kavanaugh, Mazza said he had no way of knowing whether the electrical inspector did anything in this case other than what he documented in his one-page report.

“I had asked for the office to see if they had anything further, and they said that all the records from that time had been purged,” Mazza said.

While cross-examining Beyler, Gubitose challenged the engineer’s claim that the lack of documentation meant investigators didn’t examine the building thoroughly enough.

“You’re not saying you don’t know. You’re saying he didn’t do it. … You keep saying it wasn’t done because it wasn’t documented. Right?” Gubitose asked.

“I’m good either way, because if you didn’t document it, you didn’t do it,” Beyler responded. “That is the rules of the road. You know, you can do anything you want. If you don’t write it down, it doesn’t exist.”

This story is the second part of a series about the James Carver hearing. You can read the first part, which focuses on problems with eyewitness testimony from Carver’s trial, here:

Eyewitness ID of Man Serving Life for Deadly Fire Was Unreliable, Psychologist Testifies

James Carver was convicted of murdering 15 people after an eyewitness identified him in court — but decades later, a psychologist says the identification was scientifically unreliable

I’ll be publishing more follow-up stories in the near future. The next piece will focus on the hearing’s closing arguments.

Again, if you’d like to keep The Mass Dump running, please consider offering your financial support, either by signing up for a paid subscription to this newsletter below, becoming a Patreon supporter, or sending a tip via PayPal or Venmo. It takes a tremendous amount of work to bring you stories like this, and I rely on your support to keep doing it.

Even if you can’t afford a paid sub, please sign up for a free one to get updates about this story, and please share this article on social media.

You can follow me on Facebook, Twitter, Mastodon, and Bluesky. If you have any information about the Elliott Chambers fire or the James Carver case, please email me at aquemere0@gmail.com.

Anyway, thanks for reading! That’s all for now.