Mass. State Police accidentally release birthdates of 2,000 state cops

The State Police did an oopsie!

On Tuesday evening, I was out for a walk when I got a call from a restricted number. I answered, and a woman introduced herself as Jennifer Staples, the chief legal counsel for the Massachusetts State Police. Staples said she was concerned.

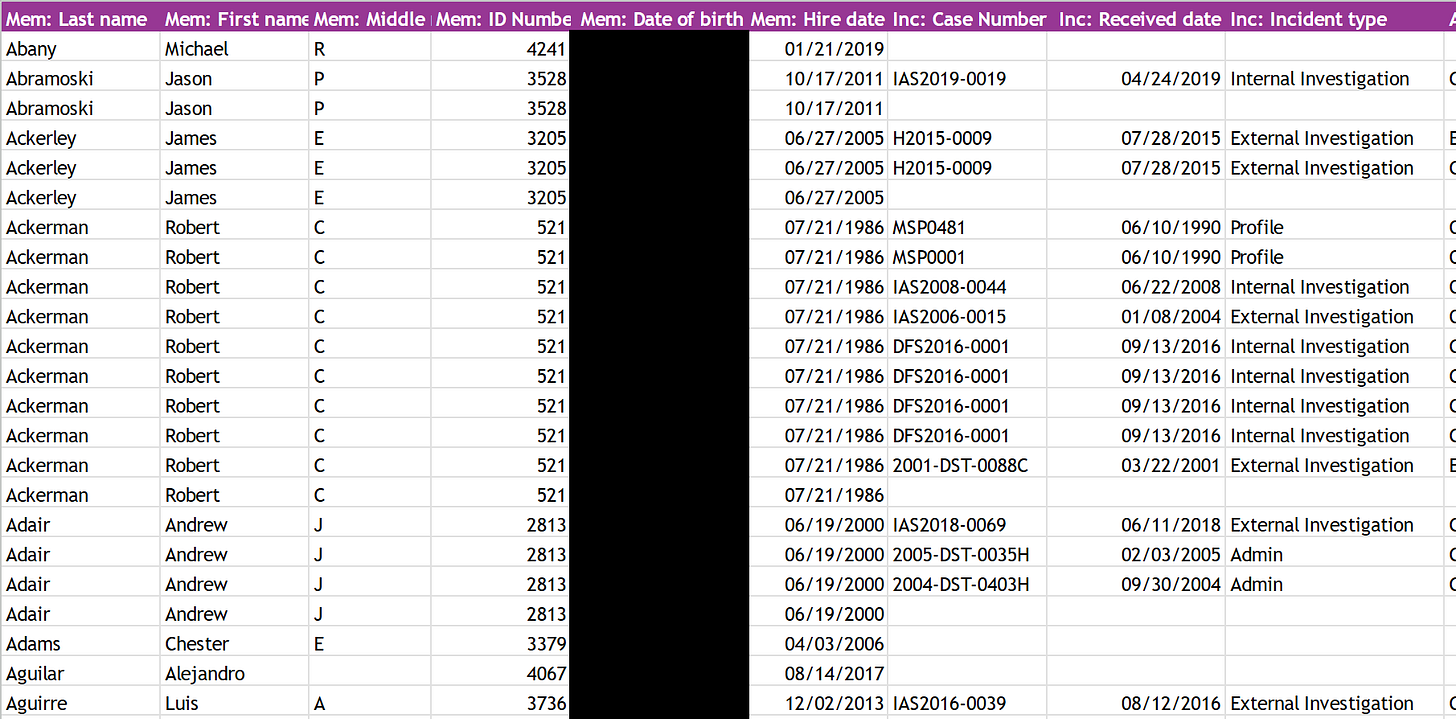

The previous day, I had published two spreadsheets that I had been sent by the State Police in February. One spreadsheet contained data about use-of-force incidents, and the other contained data about complaints. The latter spreadsheet included the birthdates of more than 2,000 state cops.

Staples said that the department provided the birthdates by mistake and asked me to remove them for “security.” I told her that I had not broken the law by publishing them. She asked me to “work with” the department. I told her to put her request in writing.

I made a public records request for this spreadsheet in April 2022. The State Police were legally required to respond to my request within 10 business days but instead took 10 months to do so. Evidently, during all that time, no one even bothered to open the spreadsheet and spend a couple of minutes looking at it.

“Unfortunately, the information we provided did not have the dates of birth of the troopers redacted, that information should have been redacted pursuant to the privacy exemption to the public records law,” Staples said in an email on Tuesday night.

She added: “We are concerned because publishing the dates of birth of troopers poses a very serious safety risk for the troopers and their families. As such, we are requesting that you remove the information immediately.”

She did not elaborate on the supposed “serious safety risk.”

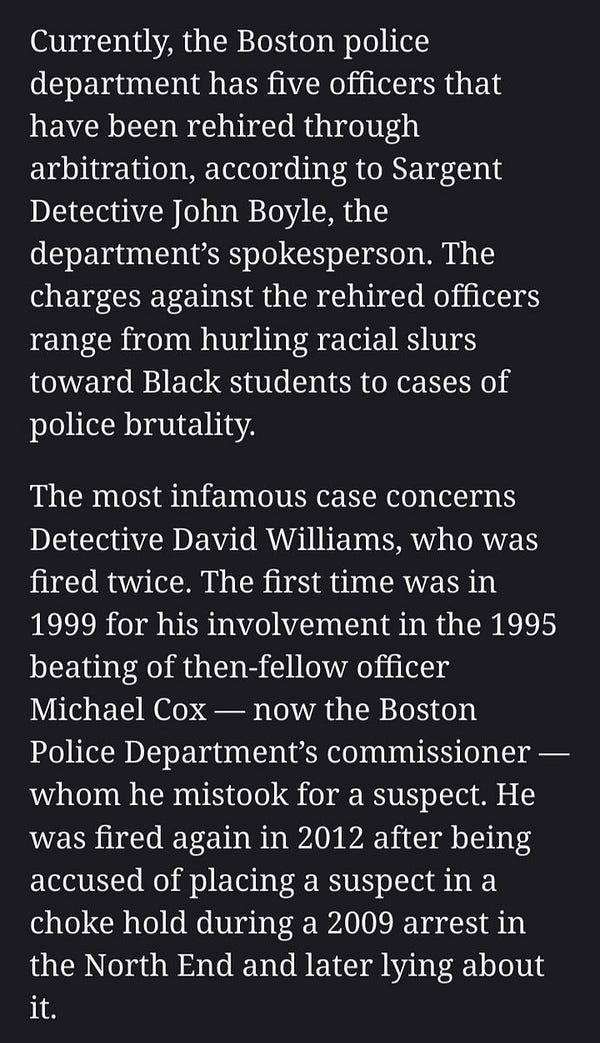

It’s not clear that the State Police would have any legal basis for withholding the birthdates. The public records law includes a specific exemption for the home addresses, home phone numbers, and personal email addresses of state employees, but there is no exemption specifying birthdates.

In 2015, the Boston Globe sued the State Police for refusing to provide birthdates in response to a records request. The Globe sought the birthdates because it needed them to request information about crashes involving state cops from the Registry of Motor Vehicles.

A Suffolk County Superior Court judge sided with the Globe, issuing a preliminary injunction and ordering the department to produce the information. However, the state Appeals Court overturned the decision in 2017.

The Appeals Court did not rule that the information could be kept confidential. Instead, it found that the lower court now needed to give both sides the chance to reargue the case in light of a Supreme Judicial Court ruling that clarified the security exemption to the public records law.

The Appeals Court noted in its opinion that “it is neither logically impossible nor intuitively obvious that the disclosure of dates of birth would jeopardize public safety.”

The case was returned to the Superior Court, where it was later dismissed because the Globe failed to take action. However, it was later reinstated and remains open.

On Wednesday, Staples sent me another email with what she claimed was a “redacted” version of the spreadsheet, asking me to use that version insead.

“Clearly, the longer the dates of birth remain public, the greater the danger increases for troopers and their families,” she said.

However, whoever created this “redacted” spreadsheet fell victim to one of the classic blunders. Instead of deleting the data, this person simply changed the background color of the cells with the birthdates to black to match the color of the text.

If you change the background color to white or to another color, all the dates become visible again. It’s also possible to view the date in a cell by highlighting it and looking at the formula bar in Excel, Google Sheets, or another spreadsheet program.

Luckily for the State Police, I know a little bit more about how spreadsheets work than they do. As a courtesy to the State Police, I removed the dates myself and replaced the old version of the spreadsheet.

After giving it some consideration, I decided it wasn’t necessary to make the birthdates public. However, I’m happy to provide the original spreadsheet to any journalists who need them for reporting purposes.

“In order to avoid issues like this in the future, I would encourage the department to review and respond to records requests in a timely manner, as required by state law,” I wrote to Staples. “If the department made meeting its legal obligations under the public records law a priority and assigned an appropriate number of personnel to this task, someone would have immediately reviewed the spreadsheet and would have noticed that these dates were included.”

Staples responded: “I understand your frustration and appreciate the feedback. We will strive to be timelier in responding to public record requests.”

I really, truly doubt it — but I’d be glad to be proven wrong.

UPDATE (same day): David Procopio, the spokesman for the State Police, declined to say why no one reviewed the spreadsheet before providing it to me.

Asked about why the department failed to properly redact the second version of the spreadsheet, he said: “The spreadsheet provided as a redacted and searchable document was reviewed, and no information was removed so as to not alter it. Rather, an attorney redacted the relevant column by changing the fill color to black, hiding the information from appearing within the formula bar, locking the spreadsheet, and protecting it with a password.”

I sent Procopio a screenshot showing that the document had not been properly redacted and that all the dates were still included. He declined to say whether the department has office clerks or IT workers who are trained to use Excel.

“We withhold dates of birth because they could be used, in conjunction with other publicly available identifying information, to commit identity theft or identify department members’ home addresses,” he said. “For the same reason, we do not release dates of birth of members of the general public, including arrestees, victims, or other persons involved with an incident.”

Procopio did not mention that the department sometimes publicizes the birthdates of people wanted for crimes.

He added: “The department complies with the public records law and continually works to strengthen our response to the several thousand of public record requests we receive each year.”

Procopio declined to say why the department unlawfully waited 10 months to comply with my request for the complaint spreadsheet or explain how the department is working to improve its compliance with the law.

If you’d like to read more reporting like this, please consider supporting my work financially, either by signing up for a paid subscription to this newsletter or sending me a tip via PayPal.

If you have any story ideas, let me know about them! You can email me at aquemere0@gmail.com or send me a direct message on Twitter or Mastodon.

That’s all for now.