No new women’s prison — and no old one either

The state wants to build a $50 million women’s prison, but activists are fighting back — and you can help

He everyone,

This is a long one (I guess all of my issues are long), and I don’t expect everyone to make it all the way to the end. But at least get to the end of the first section, because that’s where you’ll find the most important part — the part that tells you what you can do to help, which isn’t even particularly difficult.

MCI-Framingham, built in 1877, is the country’s oldest women’s prison still in operation. And it is, by all accounts, a wretched shithole where no one — woman or otherwise — should be forced to live. The latest report from the state’s Office of Health and Human Services found an endless string of code violations, including 84 repeat violations. Inspectors probably would have found more if they had been able to access the entire facility, but the issues they did document are appalling. Problems with plumbing, sinks with no hot water, lights not functioning, dusty and broken fans, rust.

And don’t forget the mold — moldy showers that prison officials didn’t bother cleaning after the previous inspection more than a year earlier. Mold is ever present at MCI-Framingham. In 2020, the State Auditor’s Office released a report concluding that the Department of Correction was failing to provide medical care to prisoners in a timely manner. The auditors weren’t looking for mold, but they found it anyway — their report noted that some medical files at the women’s prison “were quarantined and could not be obtained for review” due to an infestation.

The state’s answer to these problems is the construction of a new prison with a price tag of $50 million.

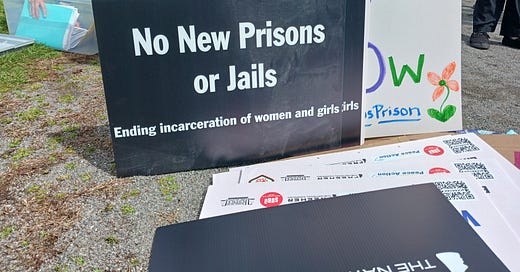

But activists have a rallying cry: “No new women’s prison!”

And many of them want to close the old one too. Their other slogan: “Free her!”

Dozens of people showed up to the Framingham Village Green last Saturday to oppose the construction project. They want the state legislature to pass a bill that would establish a moratorium on the design and construction of new jails and prisons, blocking the project and others like it from even being considered for five years.

“[I]t’s important that people realize that this bill isn’t going to prevent anyone from improving the [existing] prisons,” said Stephanie Deeley, a co-chair of the MetroWest Commission on the Status of Women who helped organize the rally. “We know that MCI-Framingham and Walpole are both in terrible condition. So you can’t blame this bill for terrible conditions. … And we in the commission support this 100 percent.”

Mallory Hanora also helped organize the rally. She is the executive director of Families for Justice as Healing, which has been the loudest voice against the proposal. The group “is led by incarcerated women, formerly incarcerated women, and women with incarcerated loved ones” and is on a mission “to end the incarceration of women and girls,” according to its website.

“Five women in their seventies [are] inside Framingham. Unconscionable,” Hanora said. “Women with significant illnesses and conditions like dementia incarcerated right down the street. Moms, grandmas, friends of ours that we just miss and love. And we just want them home, and we just need them home.”

MCI-Framingham’s population has dropped sharply in recent years, from 561 in 2015 to 166 in 2021, according to annual reports from the DOC. That 70 percent decrease is an opportunity for prison abolitionists like Hanora to make their vision a reality.

“[W]e should have a conversation with every single one of [those women] and say, ‘What do you want? What do you need? What did you need that you didn’t get? And how can you come home? Who can come home right now?’ That’s the question that we continue to ask,” Hanora said.

Fiona Hoffer, a volunteer organizer with Building Up People Not Prisons, said the state could put the $50 million to better uses.

“[E]ven if you don’t [know someone who is incarcerated], maybe you know what it’s like — because we all do — to live in a community where we are not investing in what we need to be investing in. We all know what it’s like to live in an America where we see people sharing GoFundMes for necessary healthcare,” she said.

Hoffer said she recently saw a Facebook post by a teacher asking for calculators. “This is horrible. We don’t need to live that way. There are enough resources for everyone. And we need to take them back from where they have been stolen.”

It costs taxpayers $162,260 a year to incarcerate each woman at MCI-Framingham, according to the DOC’s 2020 annual report.

For that amount of money, Hanora said, “we could pay [an incarcerated woman’s] mortgage, she could go to Harvard, that’s a guaranteed income for her. She could do whatever she wants with her life, and she should have that opportunity.”

The moratorium bill (H.1905) is currently being reviewed by the state legislature’s Joint Committee on the Judiciary and has a reporting deadline of April 15 — this Friday.

Only a few committee members have signed on to the bill so far. Representative Chyna Tyler, the House committee vice chair, introduced the bill. Representatives Brandy Fluker Oakley and Jay D. Livingstone are cosponsors. Senators Sonia Chang-Díaz and Jamie Eldridge, the Senate chair, are cosponsors of a Senate version of the bill (S.2030).

(The Senate bill is currently before the Senate Ways and Means Committee. If the House version is not approved by the Judiciary Committee, Ways and Means could still send the other version to the Senate for a vote.)

Eric P. Lesser, the Judiciary Committee’s Senate vice chair, and Michael S. Day, the House chair, did not respond to requests for comment.

On Saturday, volunteers asked Framingham residents to call or email their senator, Karen Spilka. Although Spilka is not on the Judiciary Committee, she is president of the Senate and her support could help move the bill forward. Spilka’s office did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Supporters of the moratorium bill can also contact members of the Judiciary Committee, their own legislators if they are not on the committee, and House Leader Ronald Mariano.

Justice As Healing

Families for Justice as Healing was founded by Andrea C. James while she served a two-year sentence for wire fraud in the federal prison in Danbury, Connecticut.

“During my [daily five-mile] jogs, I would listen to my commissary-purchased radio and would hear that many media outlets were finally discussing mass incarceration. But they were missing the point,” James explained in a 2017 piece for Time magazine. “What I wasn’t hearing was about the real issues that incarcerated women — the fastest-growing segment of the prison population — face every single day. So, my sisters inside and I decided that we wanted to do something about [it].”

Hanora, the group director, explained the concept of justice as healing this way: “[I]t speaks to the total illegitimacy of the criminal legal system. It’s not a place of truth or justice. It’s not a place of healing. It’s not a place of repair. … So justice as healing is a totally different framework of asking, first of all, what do people need? What do people need to live their lives in a healthy way in [a] community? What do people need to thrive? … And without punishment, without cages, without cops, without courts — but with transformative justice.”

The resources that are invested in incarceration could instead go toward services that uplift people, she explained.

“People need housing, and people need to access that housing regardless of what’s going on in their life. So housing for all people. Housing for people who are in recovery, housing for people who are using drugs, housing for people that is dignified and safe for women and their children,” she said.

She continued: “And we also need money for economic development to fund people’s small and cooperative businesses. We need money for childcare. We need money for schooling and education. So there’s so much that we could do with [$50 million]. And importantly, rather than a top-down decision-making process about that money, we need to be talking to people who are living in the most directly affected communities who should be leading the process of distributing those resources.”

Families for Justice as Healing has been instrumental in impeding the new women’s prison project. The DOC and Division of Capital Asset Management and Maintenance, which works with state agencies on construction projects and building upkeep, withdrew two calls for contractors — one in 2019 and another in 2020 — after the group protested the secretive processes the agencies used, according to DigBoston.

The DOC and DCAMM soon issued a third call for bids. According to the “Study and Design of a Correctional Center for Women” document, the state wants to build a women’s prison in Norfolk for between $20 and $40 million.

Families for Justice as Healing believes the project will cost $50 million, like the original 2019 proposal stated, or more.

“We anticipate it [will] be more,” Hanora said. “And I should say that the state’s argument is that that $50 million is actually more economical than repairing Framingham. … [P]eople are all of a sudden concerned about [the condition of] a place that has been a toxic hellhole for decades. Framingham has never been a safe place to live for women. A prison never is.”

Hanora is fed up with fighting against the continuous prison proposals.

“[P]art of the reason why we want this moratorium bill is because we don’t want to play this kind of defense for five years,” she said. “[S]o much of our time is consumed by having to fight back against this project and projects like it that we just need a pause. We need breathing room. We need to shift our focus and really be able to have the time and energy and the resources to grow what alternatives look like rather than trying to fight back against a totally unpopular, unnecessary, immoral, and irresponsible prison project.”

A “Trauma-Informed” Prison or a Trauma Factory?

The state’s proposal says the new women’s prison “must utilize the principles of trauma-informed design to create welcoming and therapeutic spaces. Landscape design should be incorporated to play a role in breaking down the institutional feeling of the correctional center by generating an outdoor environment of healing and peace in a safe and inspiring way. The Designer is expected to capitalize on an effective process to create a correctional center that contributes to the health, wellbeing, and rehabilitation of its occupants.”

But the very concept of a “trauma-informed” prison is an incoherent insult to one’s intelligence — a change of scenery doesn’t change the nature of the institution.

“The women in Massachusetts just need a little help, not to be locked away like animals. No ‘trauma-informed’ prison alternative to Framingham can accomplish these goals,” said Lauren P., an acquaintance who spent three months at MCI-Framingham in 2016 (and asked that I not use her full last name). “If we have the money to waste on a bigger, shinier cage, we have the money to invest in communities, education, and hope.”

Lauren had not been convicted of any crime during her time at the prison. She was arrested on drug-distribution charges after overdosing, then her bail was revoked when she was arrested for driving with a revoked license. As a result, she was sent to the prison’s Awaiting Trial Unit for 90 days.

After she was released, she eventually pleaded guilty to a lesser possession charge to avoid the $10,000 expense of a trial and the possibility of a mandatory-minimum sentence that would have sent her back. The Middlesex District Attorney’s Office did not seek any prison time as part of the plea deal, and she was sentenced to three years of probation. She was released from probation early on good behavior.

“The dehumanization process starts upon entry at MCI-Framingham,” Lauren said.

She remembers being strip searched upon her arrival. “Then they remove everything you need to function, in my case contact lenses,” she said. “I spent half my time at MCI-Framingham blind and with no recourse to enable me to see, besides going through the process of seeing a doctor weeks later and waiting weeks for glasses.”

A prison official asked Lauren’s cellmate to help her walk to and from the meal hall without falling.

“My cellmate was kind, but I could not read, get around, or recognize faces for at least five weeks,” she said. “Most women in prison are kind. She did not need to be there, nor did I.”

Lauren said many of the women she encountered at MCI-Framingham were, like her, there for charges related to their drug problems.

“They weren’t bad people. In fact, we supported each other more than anyone on the staff did,” she said. “The trauma, dehumanization, and long-term effects on the recovery of anyone is devastating. I still have nightmares and the walls still close in.”

Health problems were common. Lauren developed gastrointestinal issues after contracting Giardiasis, a disease caused by a parasite. A cellmate caught MRSA, a contagious staph infection, and she said prison staff did nothing to prevent it from spreading.

During her 90-day incarceration, Lauren gained 40 pounds. “The food they serve is all carbs and sugar, and when there is meat, the chicken floats in an unnatural way. Diabetes is a common problem for women who have been there for a long time,” she said.

Recently, Lauren was in an emergency room being treated for COVID-19 when she ran into another former prisoner. “She was energetic, spritely, and funny when I knew her,” Lauren said. “She had tried to cut carbs in Framingham and ended up getting kidney failure.”

The staff could be cruel. She saw a prison officer send a woman to solitary confinement for having a seizure.

“When I walked out those doors, there’s nothing that I wanted more than to leave them open behind me,” Lauren said. “The thing we all talked about [in MCI-Framingham] wasn’t crime or violence. It was how much we wanted to see our families. Mothers sharing photos of their children around the table. All these women want is to be with their families again.”

She said the plan to build a new prison is “ludicrous.”

“How many supportive programs, halfway houses, jobs programs, and the staff to run them could we fund with [$50 million]?”

Lauren did not even see the worst MCI-Framingham has to offer.

In 2020, the Department of Justice released a report detailing the results of a two-year investigation that found the DOC responded to mental-health crises with solitary confinement instead of care. The treatment was so torturous that it exposed prisoners to serious danger of self-harm and violated the Constitution.

DOC put prisoners in crisis on a “mental-health watch” that “functions, in all but name, as restrictive housing,” according to the report. Prisoners were confined to a cell for 23 or more hours a day, were kept there longer than necessary, and were provided with little help from mental-health clinicians.

“A prisoner on mental health watch is housed alone and has no interactions with other prisoners unless he yells through the crack in his cell door,” the report states.

The prisoners were supposed to be given 15-minute checks or constant one-to-one supervision, but “both officers and prisoners consistently [said] that officers do not interact with prisoners while observing them.”

The report documented a number of horrifying incidents at prisons throughout the state, including three at MCI-Framingham.

One woman was kept on mental-health watch even though staff knew it was causing her to feel suicidal, and she eventually tried to kill herself. “This incident occurred on her ninth consecutive day of mental health watch, where she remained for another 19 days,” the report states.

Another woman repeatedly harmed herself “while on mental health watch because the isolated conditions exacerbate her auditory hallucinations. … Between September and November 2018 at MCI-Framingham, she was treated at an outside hospital five times, all for injuries to herself while on mental health watch.”

In the worst incident at MCI-Framingham documented in the report, a transgender man killed himself while on mental-health watch after repeated suicide attempts. DOC staff “knew that restrictive housing settings exacerbated [his] mental health issues, yet confined him to mental health watch, where he felt particularly isolated, and also the Restrictive Housing Unit, causing him to decompensate, for the month prior to his suicide.”

“[The DOC] has cooperated with our investigation from the beginning and we look forward to working with state prison authorities to implement reform measures,” then US Attorney Andrew E. Lelling said when the report was issued.

But it’s not clear what, if anything, has changed since then. And even if anything has changed, the fact that sickening systemic abuses like these were happening at all and that it took a federal investigation for the DOC to act speaks volumes.

A DOC spokesman did not respond to a request for comment.

“Free Miss Angie”

“I’m a little emotional. I’m not gonna lie,” Shanita Jefferson, another rally attendee, told the crowd on Saturday.

Her mother, Angela Jefferson — known to supporters as Miss Angie — was convicted of first-degree murder and received a mandatory sentence of life without the possibility of parole.

Jefferson, 20 years old at the time, confronted her boyfriend, 21-year-old Anthony Deas, at the Dorchester home of another woman and stabbed him in the chest in June 1990, according to the Boston Globe. Last year, Eva Jellison, Jefferson’s lawyer, filed a motion in Suffolk Superior Court arguing that Jefferson did not receive a fair trial and either deserved a new trial or a reduction of her conviction to manslaughter.

This year, during a January 31 hearing before Judge Janet Sanders, Jefferson’s first-degree murder conviction was reduced to second-degree murder, according to Renee Algarin, deputy press secretary for the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office.

The reduced conviction made Jefferson eligible for parole.

“[My mother] is right over there in MCI-Framingham,” Shanita Jefferson said. “She has been for 31 years. Right now, we have hope. You know, we’re getting ready for her parole hearing that’s happening on Tuesday.”

She continued: “I have to say that without these people, all of you people, none of that would be possible. I literally grew up expecting my mom to die in jail. I’m from Dorchester. I said, as a little girl, I’m going to move to Framingham so that I can be close to my mom. Now, I live in Weymouth. I have my own child. And we still are back and forth here in Framingham, 31 years later — but with hope.”

Shanita Jefferson was three years old when her mother was sent to prison. Her father was murdered in Brockton a few months later. She told the Boston Herald last year that Angela Jefferson has been an “outstanding mother” and earned an associate’s degree, became a certified cosmetologist, and became a dog trainer while in prison.

“I always say she didn’t even get a first chance,” Jefferson told the Globe last year. “She made one mistake that ruined her life. And there was no consideration of who she truly was.”

But now, after decades, Jefferson’s mother has that chance.

“I mean, it’s just, it’s incredible what the power of the people can actually do. Because I never had a clue that it was this strong,” Jefferson said on Saturday. “And this is free. This is not anything that I had to sign up for. I just had to be a part of the movement, and I’m so happy that I did it.”

“We believe that she’s coming home,” Mallory Hanora said. “Miss Angie has mentored so many of the women that are in Families for Justice as Healing that did time with her. She was like a beacon of hope and love and energy and compassion to fellow women that were incarcerated, and she’s a perfect example of a grandmother who needs to come right home right now. And then women need to keep coming home right behind her.”

Angela Jefferson’s initial parole hearing was held on Tuesday.

“Miss Jefferson focused on expressing remorse and discussing her rehabilitative efforts at the hearing,” said Jellison, her lawyer.

Suffolk County District Attorney Kevin Hayden declined to comment on whether he supports Jefferson’s bid for parole.

Braving the Elements

On Saturday, it began to rain as the rally concluded, but some of the more dedicated activists gathered in a church parking lot where they prepared to canvas neighborhoods and inform Framingham residents of the prison proposal and the moratorium bill.

Fiona Hoffer, who had spoken at the rally, worked with Sage Chase-Dempsey and Ashley “Smashley” to explain the do’s and don’ts of canvassing and hand out packets of information sealed in plastic bags to protect them from the elements. After the huddle, the canvassers split off into pairs and headed out to different parts of the city.

Hoffer joined up with Chase-Dempsey, another volunteer organizer with People Not Prisons. As Hoffer drove them to their destination, they wondered if they would encounter any MCI-Framingham employees. They discussed the high suicide rate for prison officers and said they hoped the guards could find less traumatizing, more fulfilling work than caging their fellow human beings.

Hoffer drove past the Temple Street Stop & Shop and turned left onto Salem End Road. By the time she parked on a side street, the sun was out and the rain had stopped. She and Chase-Dempsey applied sunscreen as they psyched themselves up to knock on doors and speak with strangers.

They talked with a few people who seemed receptive and left flyers for those who weren’t home. But things did not go as well as they had hoped. They didn’t get chewed out by any corrections officers or pro-carceral creeps — but the weather did not cooperate.

Soon after they started, it began raining again. Then it began to pour. They heard thunder directly above them. It even started to hail. Hoffer was wearing white sneakers, which were very much not waterproof, but Chase-Dempsey had thought ahead and was wearing rain boots. Still, both were drenched, and they ended their canvassing early.

But they agreed that it wasn’t a total waste of time.

“There’s several people who didn’t know about it before who know about the new prison now and the moratorium,” Hoffer said. “Several people that hadn’t joined us before got trained on how to [canvas]. So I’d say it was a success. You always wish that rain wouldn’t get in your way, but sometimes it does, and you just keep going. Because this isn’t the only time we’re going to be door knocking.”

“I also think, comparing this week to last week, we had greater turnout,” Chase-Dempsey said. “And when you add up everyone who was out talking, … it’s kind of a large amount of people.”

“And one person knowing that this is happening and getting emboldened to change the situation is better than none. And it does add up,” Hoffer said.

Elizabeth Whalley had more luck canvassing — she found a resident willing to put up a yard sign.

Another canvasser thought she convinced two people to call Karen Spilka. “That’s not nothing,” she told her fellow volunteers back in the church parking lot.

Some of the activists intended to return on Sunday for more canvassing, and some planned on calling residents in the group’s phone bank during the week.

Speaking of which, have you called yet?

Seriously, have you called yet? These folks braved a thunderstorm and even got pelted by hail on a Saturday just to talk with a handful of people and pass out a few dozen flyers — spending a few minutes calling some state legislators is the least you can do. And if you’re phone shy, you can always send an email. Massachusetts deserves better than a $50 million house of horrors.

Look up your own legislators and reach out to them, whether they are on the Judiciary Committee or not. Reach out to Senate President Karen Spilka and House Leader Ronald Mariano. Tell them you support H.1905 and don’t want the state to build a new women’s prison — now or ever. And do it right away, because the reporting deadline for the bill is tomorrow.

UPDATE (4/15/2022): On Friday, the Judiciary Committee voted to extend the House moratorium bill’s deadline to June 30, according to Senator Jamie Eldridge’s office.

“I fully oppose the construction of any new prisons or jails in Massachusetts. Our state has one of the lowest rates of incarcerations in the country, and the prison population has declined drastically, which is why I was so encouraged that Governor [Charlie] Baker announced the closure of the MCI-Cedar Junction (Walpole) prison this month,” Eldridge said in a statement. “I support the moratorium on building new prisons in the Commonwealth, and … the committee is continuing to review [the moratorium bill].”

The extension means activists have more time to rally support for the bill and lobby committee members.

If you haven’t read enough about what an awful place MCI-Framingham is, check out the two lengthy DigBoston articles on the subject by Shelby Grebbin and Isha Marathe, one from 2020 and the other from 2021.

Finally, if you enjoyed this newsletter or were horrified by it, please subscribe — and please consider making it a paid subscription. It only costs $7 a month or $69 (nice haha) for a full year. It would be a big help, and it’s a small price to pay for informative writing like this that you won’t find anywhere else. If you are a monthly or yearly subscriber, send me an email if you want to be credited at the end of each issue; just let me know what name you want me to use.

If you go the extra mile by becoming a Dump Devotee and spend at least $200, I will make a public records request at your suggestion. I’ll reach out to you by email to discuss what records interest you and how to best go about obtaining them. If the agency doesn’t provide a response, I will file as many appeals as it takes to get one. If the agency does respond but refuses to provide the records or blacks out important information, I will make at least two additional appeals if I believe they have a chance of success. I can’t guarantee results, but I can certainly put in the effort to fight for the release of records that are important to people who make this newsletter possible.

Please send me tips! I mostly write about public records and police misconduct. I will write about anywhere in the state, and I’m always looking for new things to cover. If you have a frustrating story about trying to obtain public records or a story about the police that isn’t being told, tell me about it. You can email me at aquemere0@gmail.com or send me a direct message on Twitter.

UPDATE (4/14/2022): Added a brief statement from Eva Jellison about Angela Jefferson’s parole hearing. Jellison had previously declined to comment.

CORRECTION (4/15/2022): Clarified that the Senate version of the bill is before the Ways and Means Committee and can still pass if the Judiciary Committee does not approve the House version.