Adding Insult to Wrongful Incarceration

Massachusetts limits compensation for victims of wrongful convictions to $1 million. Advocates want to change that—but some lawmakers are seeking a compromise that would put more people behind bars.

James Lucien didn’t feel like a father when his son was born. That feeling didn’t come until two years later, when the young parent got home from work and woke the child from a nap.

“He looked at me like he just won a million dollars,” Lucien recently told a crowd inside the Massachusetts State House. “I picked him up. … And he kissed me on my lips and [said], Daddy, I love you.”

But not long after that cherished experience, Lucien was separated from his son when detectives from the Boston Police Department arrested the father for a murder he always maintained he did not commit. The separation would stretch on for more than two decades.

In 1995, Lucien was convicted and sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. In 2021, however—after he was incarcerated for more than 26 years—a judge overturned his conviction due to evidence of police misconduct that finally unraveled the dubious case against him.

Lucien was one of several exonerated men who attended an event on Beacon Hill for Wrongful Conviction Day on Oct. 2. The gathering was organized by the state’s trio of innocence programs—the New England Innocence Project, the Boston College Innocence Program, and the innocence program at the state’s public defender agency, the Massachusetts Committee for Public Counsel Services (CPCS)—to raise awareness about wrongful convictions and to push lawmakers to pass legislation that would remove the limit on compensation for victims whose convictions have been overturned. Under current state law, compensation is capped at $1 million regardless of how many years, or decades, a person was wrongfully imprisoned.

Radha Natarajan, director of the New England Innocence Project, said that 94 people have been exonerated by state and federal courts in Massachusetts since 1989.

“Together, they spent more than 1,341 years imprisoned for crimes they did not commit,” she noted.

Causes of wrongful convictions include misconduct by police and prosecutors, deceptive interrogation tactics that can foster false confessions, unreliable eyewitness identifications, and flawed forensics, according to information provided by the event organizers.

“When there’s a trial and a conviction, people say justice has been done,” state Sen. Patricia Jehlen said at the recent State House event. “Too often, we’re learning the opposite has happened, that a real injustice has started and will continue for decades.”

Jehlen is the author of legislation that would remove the $1 million cap on compensation, lower the burden of proof necessary for obtaining compensation, and provide an immediate $5,000 in financial assistance and access to social services to people whose felony convictions are overturned.

At the event, state Rep. Jeff Roy said to applause that Jehlen’s bill was given a favorable report by the Massachusetts legislature’s Joint Committee on the Judiciary in August.

However, the committee advanced its own watered-down bill that would modify the cap but not eliminate it; in some cases, the measure would actually reduce the amount of compensation that wrongfully convicted people would be eligible to receive.

The committee also merged the compensation bill with an unrelated bill that would expand pretrial detention without bail, ironically linking the issue of justice for wrongfully convicted people to incarcerating people who have not been convicted of crimes.

The expansion of pretrial detention has been opposed by criminal-justice reform groups and some state lawmakers since it was first proposed in 2018 by then-Gov. Charlie Baker, and combining it with the compensation bill could spell trouble for that proposal’s chance of becoming law.

The outcome of this legislative wrangling will impact Lucien, who filed a complaint seeking compensation from the state in Suffolk County Superior Court in February, according to court records. The Mass Attorney General’s Office, which defends the state in these cases, wrote in a court filing that it opposes Lucien’s claim. A spokesperson for the Attorney General’s Office declined to comment on the matter.

“James [Lucien] is absolutely innocent of the crime,” said his attorney, Mark Loevy-Reyes. “He was actually the victim of [a] robbery.”

Lucien alleged in court documents that the homicide victim and the victim’s half-brother robbed him of $850 while he was trying to buy drugs from them. The victim’s half-brother, who was a trial witness, attempted to shoot Lucien but the bullet missed and hit the victim, Lucien alleged.

“A notoriously corrupt Boston detective, John Brazil, took over investigating the crime,” Loevy-Reyes said. “And instead of trying to figure out … who committed the crime, he attempted to shake down the perpetrator, who was a drug dealer.”

During Lucien’s trial, Brazil produced cash that had different serial numbers from bills photographed at the crime scene, which Loevy-Reyes said was evidence the detective stole the money—something he later admitted to doing in other cases. The manipulated notes were among numerous pieces of evidence that led to a judge overturning Lucien’s conviction.

“[Brazil] fabricated evidence against James,” Loevy-Reyes said. “He was an easy target. He was present, and he was someone that nobody would believe.”

In the compensation complaint, the attorney wrote that no amount of money can ever truly make up for Lucien’s 26 years in prison. It reads: “[Lucien] spent the prime years of his life incarcerated in harsh conditions, facing physical and emotional threats. He lost invaluable time and experience with his family. The harms his wrongful conviction have caused him—emotional, physical, and otherwise—have been profound.”

Investigative journalism like this takes a ton of time, energy, and care. Before you finish reading this story, please consider signing up for a paid subscription to The Mass Dump newsletter below, becoming a Patreon supporter, or sending a tip via PayPal or Venmo to make more work like this possible.

“A way for them to avoid the responsibility”

The judiciary committee took no action on Sen. Jehlen’s compensation bill during the legislature’s 2023-2024 session. But in August, outside of the formal session, the body published a revised version, giving it a favorable report and referring it to the House Committee on Ways and Means the same day.

However, under the revised bill, only wrongfully convicted people who were incarcerated for more than four decades would not be subject to a cap on compensation. The bill would still impose a $1 million cap for people who were wrongfully incarcerated for up to 10 years. It would also impose a $2 million cap for people incarcerated up to 20 years, a $3 million cap for up to 30 years, and a $4 million cap for up to 40 years.

Sen. Jamie Eldridge, the Senate chair of the judiciary committee, said that he worked on the revised bill with the House chair, Rep. Michael Day. The result, Eldridge said, “was very much a compromise bill that reflects some of my priorities and some of the House priorities.” Eldridge said that he supports a complete elimination of the cap, but some committee colleagues opposed it. He declined to summarize their objections, saying he could not discuss the deliberations.

Loevy-Reyes was critical of the revised language, saying that juries typically award one-million to two-million dollars per year of wrongful incarceration. Furthermore, he said, jury verdicts are generally more reflective of what wrongfully convicted people deserve than an arbitrary amount set by lawmakers.

One of Loevy-Reyes’ other clients was Fred Weichel, whose murder conviction was overturned in 2017 after he spent 36 years in prison. The Attorney General’s Office—which at the time was headed by Maura Healey, the current governor—opposed Weichel’s compensation claim. Weichel took the case to a jury, which awarded him $33 million in 2022; the state, however, was only required to pay him $1 million plus legal expenses due to the cap.

Some wrongfully convicted people have been able to obtain much larger amounts of money by filing federal civil rights lawsuits, which do not have a cap. That includes Weichel, who reached a $14.9 million settlement with Braintree in September. But Weichel could have received even more were it not for the state law’s cap. Had he been allowed to collect his entire state jury award, his total compensation would have been more than $1 million per year he spent in prison.

Lucien, meanwhile, also filed a federal lawsuit against the City of Boston. Like his state compensation claim, the federal suit remains pending.

Stephanie Hartung, a staff attorney at the New England Innocence Project, said that the federal civil rights law is not a replacement for the state compensation law. The option to file a federal suit, she said, is not available to all wrongfully convicted people because it requires proving that officials committed misconduct.

“State compensation is designed to provide redress for any wrongful conviction regardless of misconduct,” she said. “There are many instances where a person may be entitled to state compensation but does not have a viable federal civil rights claim.”

Under the judiciary committee’s revised bill, if a wrongfully convicted person were to obtain money from a federal suit, then that money would be deducted from any compensation they would be eligible to receive from the state. They would even be required to reimburse the state if they received money from a federal suit after receiving state compensation.

The change would mean that some wrongfully convicted people, like Weichel, would actually be entitled to less compensation than they are now since the state would not have to pay them anything.

“I think that’s a way for them to avoid the responsibility [for] imprisoning people wrongly for decades,” Loevy-Reyes said. He said that prosecutors who represent the state government are typically immune from federal civil rights lawsuits—which means state compensation claims can be the only way to hold the Commonwealth accountable, even when it’s possible to sue municipalities and local police in federal court.

One aspect of Jehlen’s bill that the judiciary committee did not change is lowering the standard of proof for state compensation claims. Under both bills, the standard would be lowered from clear and convincing evidence to a preponderance of the evidence—the same standard used in federal civil rights cases.

“The preponderance of the evidence … that’s more likely than not, which I like to think of as 50.1 percent,” Loevy-Reyes said. “Clear and convincing is somewhere above that but not quite beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Hartung said that the lower standard is the one typically used in civil proceedings. The higher standard is unreasonable, she said, because wrongfully convicted people are being asked to “prove a negative—that [they] did not commit a crime.”

“To impose this onerous standard,” the New England Innocence Project attorney added, “is out of step with the applicable burdens in other civil contexts.”

Loevy-Reyes said that lowering the burden for state compensation claims is an issue of fairness. Even under a lower standard of proof, he said, it’s inherently difficult for people to prove that they are innocent because officials might have concealed important evidence. The passage of time also makes it difficult to locate new evidence or depose witnesses, he said.

“When evidence is hidden or fabricated, nobody says, I’m going to hide or fabricate evidence,” Loevy-Reyes explained. “You have to go digging for it. And then in a lot of instances, you have to rely on the jury to draw those inferences too, because nobody’s saying it out loud.”

Jehlen and Eldridge both said that, to get a compensation bill passed, it’s important for it to be supported by Mass Attorney General Andrea Campbell, since her office represents the state in court against compensation claims. In August 2023, Campbell told GBH that she thought the $1 million cap was “unreasonable,” and that the process for obtaining compensation was “too bureaucratic.”

“I’m having conversations with folks about what is fair in terms of compensation,” Campbell said at the time. “So we will have plans and ideas and thoughts and specifics very soon on how to revamp that process.”

Reached for comment on this story, a spokesperson for Campbell said that the attorney general supports “reforming the current system to create an administrative claims process.” According to the spokesperson, “Under this approach, those who were wrongfully convicted would no longer be required to engage in costly and time-consuming litigation against the Commonwealth to receive compensation.”

Loevy-Reyes said he would prefer that compensation claims continue to be adjudicated in court as civil cases rather than through an administrative process. “It’s awfully hard to get government actors to admit they got it wrong,” he explained. “I would rather have a jury of my client’s peers make those decisions because they’re not government actors.”

“The presumption of innocence”

In addition to modifying the compensation bill, the joint judiciary committee attached it to another bill that would expand the list of criminal charges for which people can be detained without bail.

The state’s dangerousness law permits prosecutors to request that a judge hold a hearing and detain a defendant without bail if the judge determines that “no conditions of release will reasonably assure the safety of any other person or the community.” However, prosecutors can only request a dangerousness hearing for certain charges.

Under the current law, a judge can detain a person without bail if they have been charged with any felony that necessarily involves “the use, attempted use or threatened use of physical force against the person of another,” any misdemeanor or felony involving the abuse of a family or household member, violating an abuse-prevention order, or one of several specifically listed charges like certain drug and firearm offenses.

The judiciary committee’s pretrial-detention bill would add numerous charges, such as manslaughter, statutory rape, photographing a nude person without their knowledge, criminal harassment, the violation of a harassment-prevention order, and additional firearm offenses like unlawful possession of a silencer. The proposed expansion is facing criticism from criminal-justice reform groups, including the state’s public defender agency, CPCS.

“Every day, we see clients held behind bars not because they’ve been convicted of a crime, but because they are unable to afford cash bail or are subject to pretrial detention under the guise of safety,” said Bob McGovern, the communications director for CPCS. He added: “We must remember that the presumption of innocence is a cornerstone of our legal system. Detaining individuals before trial undermines this principle and shifts the burden disproportionately onto those who lack resources to defend themselves effectively.”

State Sen. Bruce Tarr, the Senate minority leader and a sponsor of the dangerousness bill, said that expanding pretrial detention is necessary to protect “victims and potential victims … from violent offenses by defendants who have the potential to do serious harm.” He added, “The House and Senate should act on this favorable report [by the judiciary committee] as soon as possible given what is at stake for public safety.”

Eldridge, the committee’s Senate chair, was a critic of past bills to expand pretrial detention. He said the committee did its best to limit the number of charges included on the expanded list, and that he is open to criticism that it’s still too broad. Asked whether there were any specific charges he thought should he added, Eldridge said he supports including statutory rape.

According to a 2019 ruling by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, statutory rape isn’t eligible for a dangerousness hearing under current law because it doesn’t necessarily involve the use of force and isn’t specifically listed. However, the court ruled that the separate charge of forcible child rape does qualify because it necessarily involves force. Eldridge pointed to an incident from May, when a teen girl from Acton, the senator’s hometown, was killed in a murder-suicide by her stepfather, who was on bail after he had been charged with raping her three years prior. Advocates for expanding pretrial detention, including Tarr and Sen. John Velis, told the Boston Globe shortly after the teen’s murder that the case showed the need to add statutory rape to the dangerousness law.

Court records show that the defendant in the Acton case was charged with three counts of forcible child rape and that a judge determined the case involved allegations of abuse of a family or household member—meaning that Middlesex County prosecutors could have requested a dangerousness hearing under the current law.

A spokesperson for the Middlesex County District Attorney’s Office defended the decision to not request a hearing, saying prosecutors “did not have a good-faith legal basis” to seek pretrial detention because asking the judge to set bail was a reasonable alternative. According to the Globe, prosecutors requested that bail be set at $100,000, but the judge instead imposed $30,000 bail. The judge also required the defendant to wear a GPS monitor and stay away from his stepdaughter, the paper reported.

Like Eldridge, Rep. Alyson Sullivan-Almeida cited the Acton case as a justification for adding more charges to the dangerousness law. “Those are the stories that we try to deter from happening [with] this legislation,” she said. “I can understand innocent until proven guilty … but there’s enough evidence there to show that they’re too dangerous to have the freedoms of you and I.”

Sullivan-Almeida, who serves on the judiciary committee, said she was once abused by someone who was then held without bail but has heard from other survivors whose abusers were not eligible for dangerousness hearings. Asked whether the bill should add criminal harassment to the dangerousness law even though it’s a relatively open-ended charge that doesn’t involve violence, she said she supports the addition.

“So many times you hear of these criminal harassment cases where there was no violence [but] all of a sudden [they] escalated rather quickly,” the representative said. “There would still be due process in a dangerousness hearing. They would still have rights to be able to show that they, in fact, aren’t dangerous.”

Jonathan Cohn, policy director of the group Progressive Mass, said he was “just not convinced that there’s a real problem that [pretrial-detention expansion] legislation is trying to solve.” He explained: “It’s always important to recognize that anecdotes are not data. … One of the problems that can often exist for the law is [when you] legislate because of one specific incident, you don’t realize the negative ripple effects that you’re having on countless others.” Policymakers need to consider the “totality of [the] situation,” he said, including the impact on people who would be incarcerated under expanded pretrial detention.

Rep. Sullivan-Almeida and a spokesperson for Sen. Tarr both said they were not aware of any studies or data cited by proponents of expanding pretrial detention.

McGovern, the Committee for Public Counsel Services spokesperson, said that people who are held in pretrial detention are more likely to plead guilty in order to be released from jail, even if they are innocent. He explained, “The pressure to return to their families, jobs, and lives can be overwhelming, and many innocent people make the devastating decision to plead guilty rather than endure months or even years of pretrial detention.”

Janhavi Madabushi, director of the Massachusetts Bail Fund, a nonprofit that posts bail for people who cannot afford it, said that data from the Massachusetts court system show that the “dangerousness [law] is factually racist in its enforcement.” According to court data, in FY2024, about 26% of dangerousness hearings involved Black defendants, while about 32% involved Hispanic/Latino defendants, the vast majority of whom were men. Black residents make up about 10% of the state’s population; Hispanic residents make up about 14%, according to census data.

“There has been no researched evidence to show that holding people without bail, on dangerousness, keeps people safe,” Madabushi said.

“We will continue to face resistance”

It’s unlikely that state lawmakers will vote on the judiciary committee bill this year, since it was published in August, after the legislature’s formal session ended.

However, if the committee continues its approach of merging issues next session, expanded pretrial detention could prove to be a poison pill that prevents the compensation bill from moving forward. Sen. Jehlen said she did not know why the committee linked the two bills. “I think [the compensation] bill deserves to be considered by itself,” she said. “I don’t like this process of attaching bills to unrelated ones that are more controversial.”

It’s unclear why the judiciary committee chairs merged the proposals. Under the legislature’s rules, joint committees conduct their deliberations—and even their votes—in total secrecy. “It speaks to the general opacity of how the legislature operates that they never have to actually provide explanations for what they do,” said Cohn of Progressive Mass. “You’ll have public hearings, but nothing that the committees really do beyond the hearing … happens in public.”

Sen. Eldridge said that the judiciary committee’s compromise bill “was not perfect,” but that he will try to improve it during the next session. The Acton official added that by giving the bill a favorable report, the committee signaled that the issue of compensation for victims of wrongful convictions should be a priority for lawmakers next year.

However, Cohn said the messaging was weakened by “not giving that bill its own clean report and merging it with something else because they wanted to report [it] out.”

Natarajan, the New England Innocence Project director, said her group is grateful the committee supports raising the cap on compensation, but agrees with Jehlen that the proposal should be considered on its own. “We do not support efforts to increase pretrial detention or punishment,” Natarajan said.

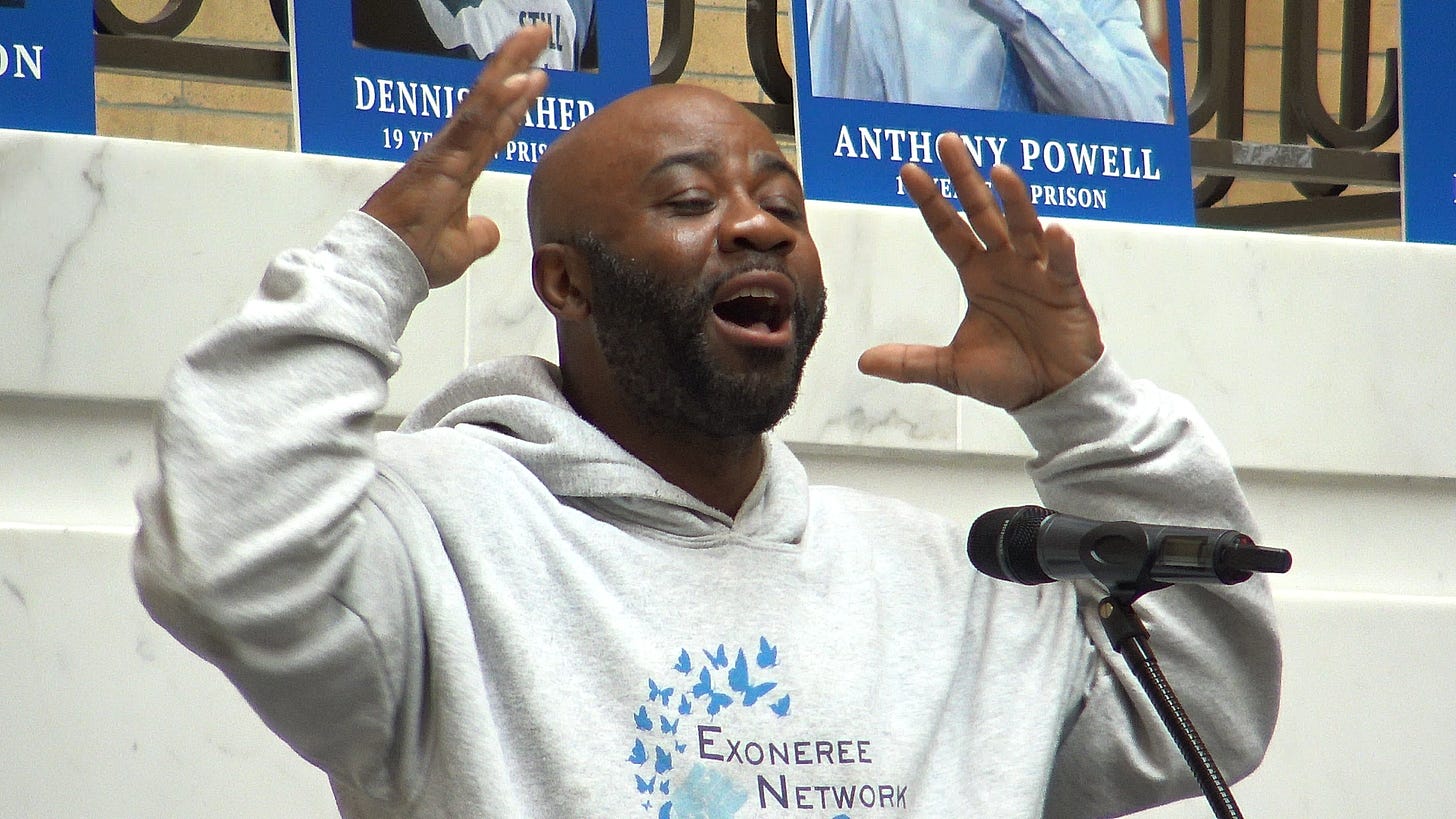

During his Wrongful Conviction Day speech at the State House, Lucien recounted when a judge sentenced him to life in prison: “It [was] like a stab in my chest. He was basically saying, Yo, you’re going to die in prison. I’m sentencing you to death by incarceration. It hurt.”

Lucien said he hugged his young son for what he thought might be the last time, then was brought back to his cell and cried. “I vow to myself that I’m not going to give up,” he said. “Not for … me, but I’m not going to give up for my son.”

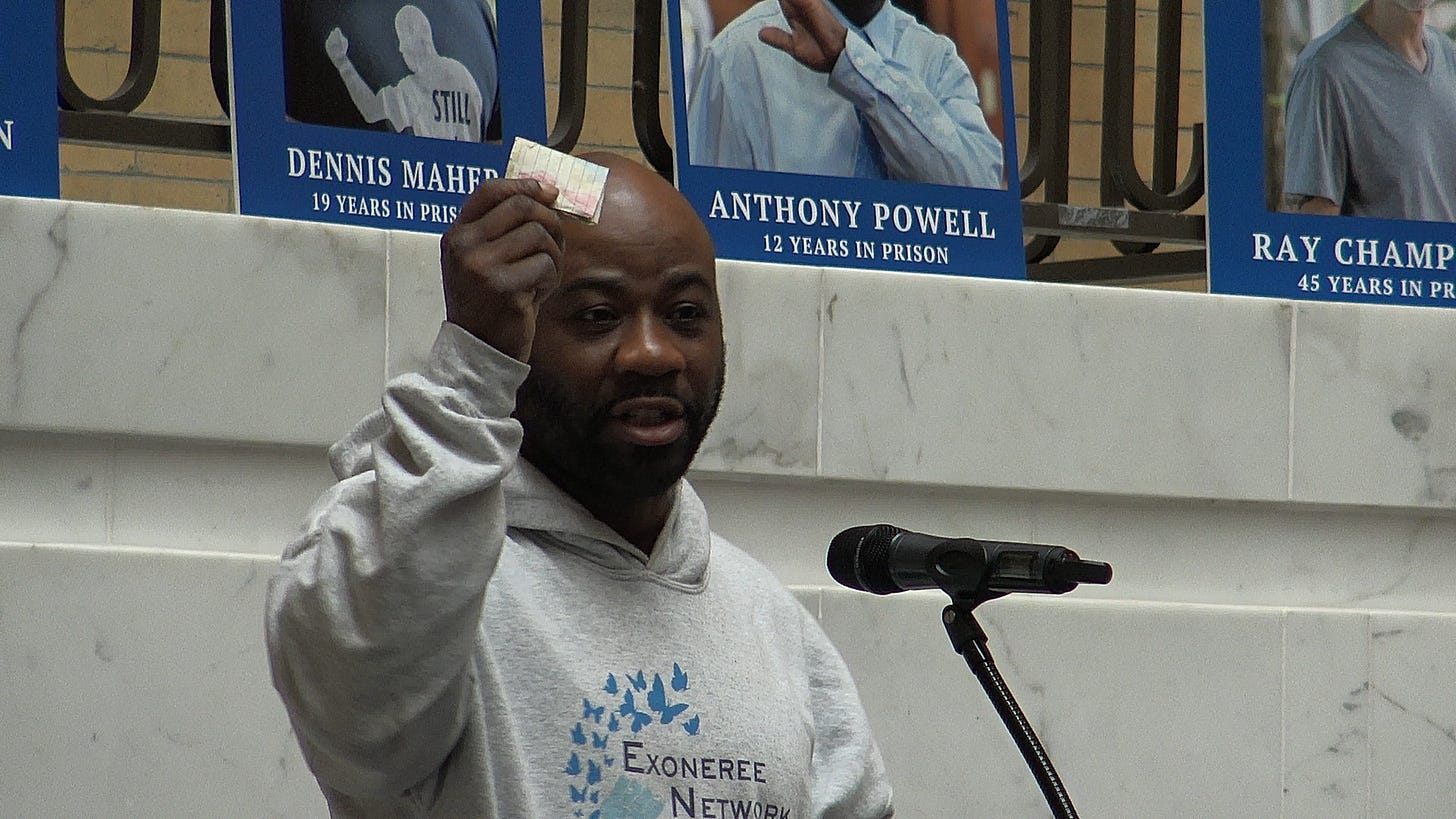

During his 26 years in prison, Lucien frequently wrote home, and at the State House, he produced the first letter he received from his son, who was five years old when he sent it.

“Daddy, you’ve been far away,” Lucien read. “I know you miss me, and I miss you too. But when you get home, we’ll be a happy family. We’ll have fun.”

When Lucien was finally released from prison, he reunited with his son.

“When I seen him again, my son, [he was] six-foot-six, looking down at me,” Lucien said. “Despite how big he was, he was that two-year-old, that little two-year-old that said, Daddy, I love you. Though this time … it was [with] a deeper voice.”

After the event, Lucien, Natarajan, and a group of other exonerees, family members, and advocates marched to Boston City Hall while chanting to beats supplied by drummers from the group Grooversity. As they marched, the demonstrators held signs with photos of dozens of incarcerated people who are fighting to get their convictions overturned.

“Here we stand between City Hall, the Attorney General’s Office, the Suffolk County courthouse, the district attorney’s office, the governor’s office, and the State House,” Natarajan said into a megaphone.

“Listen,” she continued, “the power does not sit with those officials around us. It is right here in this community. And even though we will continue to face resistance—because that’s what we face every day—this community is not backing down.”

CLARIFICATION (11/4/2024): This story was updated to reflect the fact that the State House event was organized by three groups, including the Boston College Innocence Program and the CPCS Innocence Program, not just the New England Innocence Project.

This article was a collaboration between the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism and The Mass Dump, and is syndicated by the MassWire news service of BINJ.

Thanks for reading, and sorry that it took me longer than expected to finish it.

Again, if you’d like to keep The Mass Dump running, please consider offering your financial support, either by signing up for a paid subscription to this newsletter below, becoming a Patreon supporter, or sending a tip via PayPal or Venmo. It takes a tremendous amount of work to bring you stories like this, and I rely on your support to keep doing it.

Even if you can’t afford a paid sub, please sign up for a free one to get updates about this story, and please share this article on social media.

You can follow me on Facebook, Twitter, Mastodon, and Bluesky. You can email me at aquemere0@gmail.com.

Anyway, thanks for reading! That’s all for now.