Civil rights groups call on Mass high court to keep police misconduct records public

Civil rights groups and state’s police certification agency slam Bristol County DA’s sweeping arguments for police secrecy

Things are looking a little awkward for Bristol County District Attorney Thomas Quinn.

Ever since a Fall River police officer shot and killed 30-year-old Anthony Harden in November 2021, Quinn has been on a quest to keep records about the shooting from the public — even after his office closed its investigation and issued a report saying the shooting was justified.

To justify blacking out the names of officers and withholding surveillance video, photographs, recorded interviews with officers and EMTs, and other records, Quinn’s office seized on the 2020 police reform law that established the Massachusetts Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST) Commission, the state agency that oversees police certification.

In a brief submitted to the highest court in the Commonwealth, Quinn’s office argues that only the POST Commission has the authority to release the names of officers investigated for alleged crimes and other misconduct. The 2020 law does not say this — in fact, lawmakers included language to expand access to records of such investigations — but Quinn’s office argues that the creation of the POST Commission implies unwritten changes to the Public Records Law that make police less transparent.

However, the DA faces a big problem: The POST Commission itself disagrees with this interpretation of the law.

In February 2022, Harden’s older brother Eric Mack sued Quinn’s office for records about the investigation. Mack told the Lights Out Mass podcast in October that he believes Quinn is “hiding something,” pointing to inconsistent statements police made about how they located a steak knife in Harden’s apartment after the shooting.

Suffolk County Superior Court Judge James Budreau ruled against Quinn in March, ordering the DA’s office to release all the records. In September, Budreau also ordered the DA’s office to pay $44,000 for Mack’s legal fees and $1,000 in punitive damages.

However, Quinn’s office appealed to the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, asking the high court to hear the case without it first being reviewed by the state Appeals Court. The SJC agreed to hear the case and asked interested parties to submit amicus curiae (friend of the court) briefs discussing the legal issues raised by Quinn’s office.

Since then, the case has become a flashpoint in the ongoing struggle to make policing more transparent and accountable, with an assortment of organizations — including the POST Commission, The Mass Dump, eight civil rights groups, and another DA’s office — submitting a total of five amicus briefs. Of the five briefs, four criticize Quinn’s sweeping arguments for secrecy of investigations of police shootings and alleged misconduct.

“The fact that the SJC accepted this on direct appellate review, rather than waiting for it to percolate through the Appeals Court suggests our highest court is very interested in resolving this issue sooner rather than later,” said Daniel Medwed, a Northeastern University law professor who is not involved in the case. “Similarly, the solicitation of amicus briefs is a sign that the issue is at the forefront of the justices’ thinking and that they want as much information as possible to assist them in addressing it.”

Several of the briefs criticizing Quinn’s office point to the 2020 law’s updated language that says the Public Records Law’s privacy exemption “shall not apply to records related to a law enforcement misconduct investigation.”

But Quinn’s office argues that because it said the Harden shooting was justified, the investigation wasn’t a misconduct investigation and the privacy exemption applies to the officers’ names and other records.

The only organization to support Quinn’s interpretation of the law is Northwestern District Attorney David Sullivan’s office.

Both Quinn and Sullivan’s offices are facing separate lawsuits by the Dump for refusing to disclose records about police misconduct investigations. The Dump and the two DA’s offices agreed to pause both cases until the Supreme Judicial Court rules on Mack’s lawsuit because the decision is likely to impact them.

The Dump is represented by Mason Kortz, a clinical instructor at Harvard Law School’s Cyberlaw Clinic; Kortz was assisted on the amicus brief by law students Angela Li, Pedro R. M. Silva, and Ellen Teuscher. The Dump’s team collaborated on its brief with attorneys Jessica Lewis and Dan McFadden of the American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts and Rebecca Jacobstein of the state’s public defender office, the Committee for Public Counsel Services.

Brief “Speaks Volumes”

Quinn’s office argues that the “intent and language [of the 2020 police reform law] show that the names of the officers in these records should not be released publicly without the thorough consideration by the governmental agency that was specifically authorized by the Legislature to do so.”

But the POST Commission’s amicus brief argues that the 2020 law does not create any new exemptions to the Public Records Law or make the commission responsible for responding to records requests directed to cities, towns, and other state agencies.

“The Legislature clearly did not intend to … excuse all agencies other than the [POST] Commission from disclosing the names of investigated officers,” the brief says.

“The Legislature knows how to create exemptions that make records unavailable to the public where those records are in the possession of particular agencies and reflect the names of certain individuals,” the brief continues. “[T]he complete absence of language creating a public-records exemption for the names of investigated officers in the possession of agencies other than the Commission should be deemed deliberate.”

Mack said that the POST Commission’s brief “speaks volumes.”

“Even the agency which DA Quinn claims has exclusive jurisdiction disagrees with him,” Mack said. “Their arguments are completely baseless, and that is why they lost at the Superior Court. This is all about delaying producing the evidence.”

Medwed was more ambivalent when asked about the significance of the commission’s brief.

“I’m not sure about whether the SJC will give much weight to the POST Commission view on this, given that the organization is still in its infancy,” he said. “But the notion that the commission itself believes that it is not the sole entity with this power is very telling, in my mind at least, because it reflects the commission’s understanding of its powers and responsibilities in relation to other actors.”

Notably, the brief is silent about Quinn’s argument that an investigation is only a misconduct investigation if investigators conclude there was misconduct.

“The Commission takes no position on the other questions posed by the [Supreme Judicial] Court’s request [for amicus briefs], nor does it take a position on the proper disposition of this appeal,” the brief says.

In August, the POST Commission published its police disciplinary database, which the 2020 law required it to create. The commission only included complaints that investigators “sustained” — meaning cases in which investigators concluded that officers had committed misconduct.

When the commission began its work on the database in 2021, it collected information about complaints that weren’t sustained. However, it later changed course and decided it would not publish that information.

POST Commission executive director Enrique Zuniga told The Boston Herald in August that the commission received data about 36,000 complaints from law enforcement agencies by the end of December 2021, but only 12,000 of the complaints were sustained.

The commission then asked agencies to resubmit their data and exclude “information on people who have since retired or resigned in good standing,” Zuniga said, which cut the number of complaints that the commission first published down to just 3,413 — less than 10 percent of the total.

Sullivan, the Northwestern DA, argues that this limited database is the only information about police misconduct investigations that the public should be allowed to access. If the SJC adopts this interpretation of the law, it would allow Sullivan’s office to withhold the names of officers accused of crimes and other misconduct, which are at issue in the Dump’s lawsuit.

“If [a] record is not present on the POST website, it informs the public that POST has not found misconduct warranting revocation or suspension of certification or retraining,” the amicus brief by Sullivan’s office argues. “Its absence from the POST [sic] publicly available database indicates that the record is only relevant to a district attorney’s obligations to provide discovery to a defendant’s counsel in a criminal case or in fulfillment of other duties.”

“Schrödinger’s Investigation”

The Dump’s amicus brief, and two other briefs by civil rights groups, argue that Quinn’s interpretation of the 2020 police reform law conflicts with its language and purpose. The three briefs criticize the DA’s argument that an investigation isn’t a misconduct investigation unless investigators say they found misconduct.

“Beyond offending logic, this argument would read the changes made by the Legislature to [the privacy exemption] as restricting, rather than expanding, public access to records about potential law enforcement misconduct, defeating the purpose of the 2020 [law],” the Dump’s brief argues.

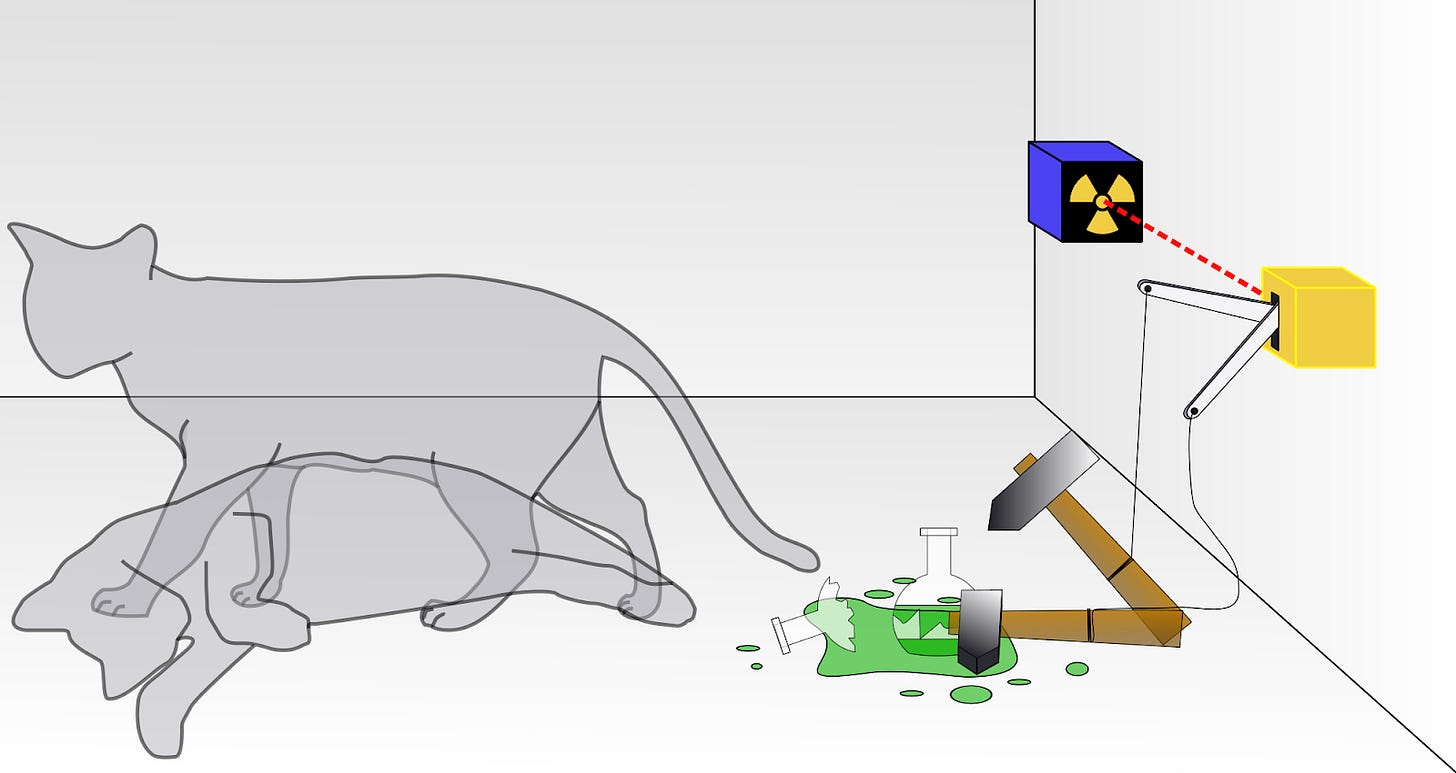

“[Quinn]’s novel theory of ‘Schrödinger’s Investigation’ must fail,” the brief continues. “Unlike the proverbial feline, the nature of an investigation is known and defined by the investigator’s mandate, actions, and objectives long before the outcome is known.”

The Dump’s brief points to past cases about police misconduct records as precedent, including a 2003 Appeals Court decision that determined internal-affairs records are not private personnel records. A 2020 Supreme Judicial Court decision also cited in the brief held that arrest reports related to police officers and other public officials cannot be withheld under the privacy exemption or the state’s Criminal Offender Record Information (CORI) law, which protects some records about people’s criminal history.

“[G]iven the public interest in obtaining information concerning police officers’ use of deadly force, it would be perplexing for records related to such an investigation to be exempt from the amended Public Records Law,” the brief argues. “The public has a right to examine investigations that did not find wrongdoing for inconsistencies, incompetence, and corruption.”

The Dump’s brief also points out that criminal defendants use the Public Records Law to obtain information that is beneficial to their cases and argues that cutting off their access to this information would “have deleterious consequences on the administration of justice.”

Another amicus brief was written by Lawyers for Civil Rights Boston, Citizens for Juvenile Justice, the National Lawyers Guild, the New England First Amendment Coalition, and Strategies for Youth. It accuses Quinn’s office of “hid[ing] behind semantics to … avoid its disclosure responsibilities.”

“The District Attorney’s interpretation would also create a perverse incentive for investigators to conclude that no misconduct had been committed to avoid disclosure,” the Lawyers for Civil Rights brief argues. “The close relationship between the police officers whose conduct is being scrutinized and the District Attorney making a charging decision renders the public interest in transparency particularly acute.”

An amicus brief by the National Police Accountability Project (NPAP) points out that the 2020 law was passed in response to protests over the police murder of George Floyd.

“The events of summer 2020 fanned the flames of deep distrust between the public and law enforcement,” the brief says. “In passing the [police reform law], the Legislature sought to address this lack of transparency and accountability.”

The brief notes that “a significant number of high-profile police killings (including in Massachusetts) have occurred in the last several years.” It lists Terrence Coleman, who a Boston police officer shot to death in 2016, and Juston Root, who Boston police and a state trooper shot to death in 2020, among other examples.

The Supreme Judicial Court will hear oral arguments in Mack’s case on December 6.

Journalism like this takes a ton of time, energy, and care. Please consider signing up for a paid subscription to The Mass Dump or sending a tip via PayPal to make more work like this possible.

You can also follow the Dump on Facebook, Twitter, Bluesky, and Mastodon.

It was awesome to have a chance to work on an amicus brief in this case, and I’m very pleased with the results — I just hope the justices on the Supreme Judicial Court find our arguments convincing. You can read the full brief here.

I want to thank my lawyer, Mason Kortz, and his students, Angela Li, Pedro R. M. Silva, and Ellen Teuscher. I also want to thank Jessica Lewis and Dan McFadden (who came up with the “Schrödinger’s Investigation” line) of the American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts and Rebecca Jacobstein of the Committee for Public Counsel Services. While I did do some work on the brief, they deserve the vast majority of the credit.

Check back in December for a story about the oral arguments, which will give us some hints about how the justices might decide the case.

Last week, The Shoestring published this story by Shelby Lee about their fight to access weapons inventories from six police departments, which have refused to produce the information. After detailing the maddening, Kafkaesque process that they went through to fight for the records, Lee explains why the state’s Public Records Law is so weak with an assist from me:

Transparency advocates consistently rank Massachusetts as one of the most opaque states in the entire country. It is the only state in which the Legislature, Judiciary and governor’s office all claim to be exempt from the public records law. The state’s Public Records Division has no meaningful way to enforce its decisions if a record keeper refuses to comply.

The supervisor of records can refer the issue out to the attorney general’s office, but once a records dispute enters into this area it can be a long time before it is reviewed. There is no timeline in which the AG’s office has to investigate the issue once it is referred to them, and very few cases ever even make it that far .

Until significant changes are made to the records law, the only recourse available for those being denied public records is obtaining representation and going to court. This lengthy and expensive process allows municipalities to greatly delay the release of records and dodge transparency to the public.

In June, independent journalist Andrew Quemere sued the Northwestern District Attorney’s Office over their refusal to hand over records relating to police misconduct. In a phone interview with The Shoestring, Quemere said the “glaring issue” and “root of the problem” with the state’s current public records system is the lack of enforcement power held by the supervisor of records.

“The whole system is based on the idea that the burden is on the agency but literally everything is on you,” Quemere said. “You have to keep bugging the supervisor to get help.”

Quemere said that he, like The Shoestring, has received “comically vague” responses from the supervisor “ordering agencies to provide a lawful response or that some records or portions of records may potentially be exempt.”

Quemere also said the Public Records Division doesn’t use the power that it does have.

“These people do know the law,” he said. “So it’s bizarre, they are allowed to insert their own judgment until a court has contradicted them in some way, but they just don’t make use of that power.”

Quemere described the process of seeking representation for such cases as difficult and time consuming. He found in his search for representation that it is a sort of niche area of law practice and the prospects of attorneys recuperating adequate compensation for their time spent on the case is minimal. Attorney’s fees may be requested and awarded if a public records lawsuit is successful, but ultimately it is up to the judge presiding over the case to determine the amount.

Read the full story here.

Also last week, Shelby Lee joined fellow Shoestring reporter Dusty Christensen and Northampton Policing Review Commission member Dan Cannity for a panel discussion titled “Police Accountability and the Media.” It’s definitely worthy of a listen, especially if you live in Western Mass.

Again, if you’d like to keep The Mass Dump running, please consider offering your financial support, either by signing up for a paid subscription to this newsletter or sending a tip via PayPal.

If you have any story ideas, let me know about them! You can email me at aquemere0@gmail.com.

If you’ve got some free time during the long Thanksgiving weekend, check out the most recent episode of Lights Out Mass, which is an in-depth discussion with investigative reporter Todd Wallack.

Pulling Back the Curtain on Government Secrecy (with Todd Wallack)

Listen now (67 mins) | Veteran investigative journalist discusses his legal battles to expose information about state officials, police, and the legal system

That’s all for now.