“Ain’t Nobody Helping Me.” More Calls For Reforms To Massachusetts Wrongful Conviction Compensation Law

Legal advocates have long said the commonwealth’s system for compensating victims of wrongful convictions is unfair, and now they have a plan to fix it

After spending 39 years in prison for a murder and armed robbery he said he did not commit, Albert Brown had a question for Massachusetts state lawmakers: “Why am I still being treated unfairly?”

In 2022, a court overturned Brown’s convictions. A judge found that prosecutors failed to disclose statements by the case’s key witness that contradicted his trial testimony and undermined his credibility. But Brown recently said that he still hasn’t received any money from the state for the decades he spent behind prison walls. His voice cracked as he told lawmakers about how many of his family members died while he was in prison: his mother, his grandmother, and three aunts.

“I got some kids, but I don’t know them,” Brown said at a June hearing before the state legislature’s Joint Committee on the Judiciary. “I’ve been gone 40 years out of their lives, and they was tots when I left. … All my old friends from 40 years ago are gone, and everybody tells me they either died or moved away.”

Legislation could change wrongful conviction compensation in Massachusetts

At the June hearing on Beacon Hill, Brown and other advocates testified in support of a bill that would update the commonwealth’s system for compensating victims of wrongful felony convictions.

Under the current law, a victim must file a lawsuit against the state and prove their innocence to a jury to receive compensation. The process can take years, and advocates say the system delays justice for people who have already spent years—often decades—incarcerated for crimes they did not commit. The proposed legislation would replace the existing procedure with an administrative process overseen by the Massachusetts Attorney General’s Office, which currently defends the state against compensation lawsuits.

Brown filed a complaint seeking compensation from the state in Suffolk County Superior Court in September 2023, according to court records.

“I don’t understand why I need to go to court again to fight for compensation,” Brown told lawmakers. “I fought for 40 years to get out of prison. … So now I’m here. Where’s the compensation? Ain’t nobody helping me.”

The Massachusetts Attorney General’s Office wrote in a November 2023 court filing that it “denies that [Brown’s] conviction was unlawful or erroneous” and opposes his compensation claim. A spokesperson declined to comment on the specifics of Brown’s case. However, she said that the AGO often reaches settlements under the current law but “cannot do so unless and until we have fully vetted the claims, and the current model for doing so is through litigation.” The spokesperson added that even when the AGO wants to settle a case, it must go to trial if it can’t reach an agreement on the amount of compensation.

Under the proposed update, victims of wrongful felony convictions would no longer be required to file a lawsuit. Instead, they would need to provide the AGO with documentation showing they meet the eligibility requirements for compensation and possibly attend an administrative hearing for which they would be appointed an attorney if they could not afford one. Under timelines specified in the bill, the complete process would take four months or less if neither party filed an appeal.

To establish eligibility, the victim would need to provide a sworn statement that they are innocent. They would also need to show that a state court overturned their felony conviction “on grounds specific to [their] case,” and that they were then acquitted at a retrial, prosecutors dropped the charges, or a judge dismissed them. Alternatively, they could show that the governor pardoned them because of “a reasonable possibility” that they are innocent. The bill would do away with the current law’s $1 million cap and instead guarantee victims at least $115,000 per year of incarceration. It would also entitle victims to tuition waivers at state and community colleges, MassHealth insurance, and housing assistance.

A victim could also request $15,000 in transitional assistance from the court that overturned their conviction. The court would be required to order payment within 30 days of the victim’s release from prison, giving them some money to address their immediate needs. The court would also be required to authorize funding for a social-services advocate to help the victim obtain “transitional services including, but not limited to, referrals for their physical, social and emotional needs.”

How legal advocates and the Attorney General’s Office collaborated on the exoneree bill

Sen. Patricia Jehlen, who filed the bill in the Senate, said it represents the first time that exonerees, innocence lawyers, and the AGO have all agreed on how to reform the compensation law.

Radha Natarajan, director of the New England Innocence Project, testified in support of the bill, saying that after victims of wrongful convictions are released from prison, they “struggle to find a place to live, get an ID, afford basic necessities, navigate changes in this world, and make up for decades of distant relationships. And they continually struggle with the trauma of incarceration.” She said that “exonerees are forced to retain a lawyer, file civil litigation, sit for depositions, and fight for years” to get compensation under the current law.

Amanda Hainsworth, a senior legal advisor to Massachusetts Attorney General Andrea Campbell, testified that the bill would “allow eligible wrongfully convicted individuals to receive compensation through a faster, more efficient, more equitable, non-adversarial process.”

“This legislation is the product of nearly two years of extensive collaboration between the Attorney General’s Office … and the innocence bar,” Hainsworth said. “We came together to work on this legislation, because … we all know firsthand that the current litigation-based model serves no one.”

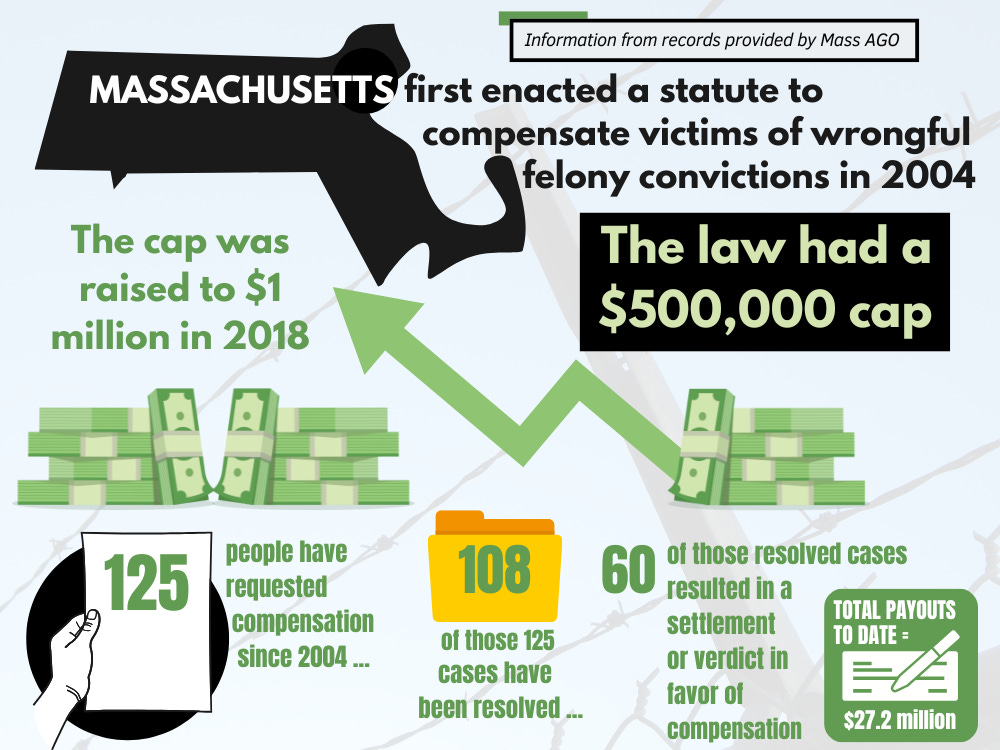

The state first enacted a statute to compensate victims of wrongful felony convictions in 2004. The law had a $500,000 cap, which was raised to $1 million by a provision in a 2018 criminal-justice reform bill. Since the law first took effect, 125 people have requested compensation, according to records provided by the AGO. Of the 108 cases that have been resolved, 60 resulted in a settlement or jury verdict in favor of compensation, with payouts totaling $27,153,300, not including legal expenses.

Seventeen cases are pending in superior court or in the pre-litigation phase. If the bill is passed, those with pending complaints will have the option to move their cases to the new administrative system.

To become law, the bill first needs a favorable report from the judiciary committee. In October, the committee gave a favorable report to an older version of Jehlen’s compensation bill that did not include an administrative process. However, the committee joined it to another bill that would allow courts to hold more people in jail before trial, a proposal that criminal-justice reform groups opposed. The combined bill, which the judiciary committee approved outside of the legislature’s formal session, is now dead.

The combined bill was negotiated by the judiciary committee’s House chair, Michael Day, and then-Senate Chair Jamie Eldridge, who is now the Senate vice chair. Day did not respond to an interview request. Eldridge and the current Senate chair, Lydia Edwards, declined interview requests.

Jehlen said she doesn’t know why the committee joined her bill with the pretrial-detention bill last year. She hopes the new version passes on its own this session: “I have much more confidence now, because … it’s been negotiated with the attorney general.”

If the legislature passes the bill, it will go to Gov. Maura Healey’s desk. In 2018, while serving as attorney general, Healey told GBH that she “would like to explore with the legislature if there could be a different process set up” for compensating victims of wrongful convictions. She also said she wanted to lower the standard for proving innocence. However, when contacted for this story, a spokesperson declined to say whether Healey still holds those opinions.

“The governor will review any legislation that reaches her desk,” the spokesperson said.

Sean Ellis and other exonerees explain the need for immediate help and services

Advocates said at the June hearing that getting compensation to exonerees faster is crucial so that they can move on with their lives.

Sean Ellis, the subject of the harrowing Netflix documentary series “Trial 4,” told lawmakers that when he was released from prison, the only thing he owned was a folder containing legal documents. In 2015—after Ellis had spent 21 years incarcerated for a murder he said he did not commit—a judge overturned his conviction due to evidence of police misconduct. Ellis is now the director of the Exoneree Network, a group he co-founded to help other wrongfully convicted people transition from incarceration to freedom.

Ellis said that during his own transition, he had to rely on others for support. He said his sister gave him a cell phone, he received financial help from friends of his family, and he lived with another family he didn’t know that opened up their home to him.

“I was thankful to be home,” Ellis said. “Yet I had to learn to navigate a living space that I was sharing with strangers while being fresh out of prison. Dealing with these things post-release perpetuated the trauma that I experienced while in there.”

Under the proposed legislation, a person could apply for compensation 60 days after a judge vacated their conviction. The AGO would be required to order immediate payment if the applicant established their eligibility. If the AGO did not believe that the applicant established their eligibility, it would be required to hold an administrative hearing within 60 days. The AGO would then be required to provide a written decision within 60 days of the hearing.

At the hearing, the applicant would have the burden of proving that they meet the eligibility requirements by a preponderance of the evidence, which is lower than the clear and convincing evidence standard mandated by the current law.

Sharon Beckman, director of the Boston College Innocence Program, said the standard required by the current statute is the highest in civil law, noting that it is used in cases to terminate parental rights. She said the lower standard is the one used in most civil cases and that the proposed administrative process, with its lower burden of proof and strict timelines, would be more fair to victims of wrongful convictions than requiring them to spend years in court.

“I don’t think people fully understand how stressful litigation is, and these are people that have been litigating for their freedom already—for decades,” Beckman said.

Removing the need for litigation would also save the state money, she noted, since lawyers for victims and the state would no longer need to reinvestigate the facts of complex, decades-old criminal cases or engage in a protracted discovery process.

Replacing a jury-trial system with an administrative process

Mark Loevy-Reyes is a Boston-based attorney who litigates civil wrongful conviction cases in state and federal courts around the country, including in Massachusetts. He said that he agrees with the aim of speeding up the process for obtaining compensation.

“A lot of my clients … served decades wrongfully in prison, and when they’re released, they’re older people,” he said. “It doesn’t really serve their interest to litigate a case over multiple years, when, in fact, what they need is immediate help.”

Loevy-Reyes said he has some concerns about replacing a jury-trial system with an administrative process but isn’t necessarily opposed to it: “The government’s deciding whether it’s going to pay is problematic because it has an inherent interest in not paying, whereas when a jury’s deciding, it doesn’t have the same interest.”

However, Loevy-Reyes said the simplified eligibility requirements in the bill would “definitely [be] a major improvement, and if done fairly, would be a better process.”

“My concern is not about the reform,” he said. “It is about whether the commonwealth can be trusted to implement the compensation system fairly. I truly hope so.”

The AGO is responsible for defending state agencies—including district attorney’s offices and the Massachusetts State Police—from all manner of lawsuits. Asked about the possibility that the AGO would not be able to impartially administer the compensation process due to its relationship with these agencies, a spokesperson said: “While we are still determining the exact entity, the entity overseeing the administration of these claims will not be housed within the bureau that represents state agencies.”

The spokesperson also noted that the bill includes “a meaningful right of appeal.” The bill would give both sides the option to appeal the decision to a state agency called the Division of Administrative Law Appeals (DALA). If either party disagreed with DALA’s decision, they would be able to file an appeal in superior court under an existing provision in state law.

However, Beckman said that the legislation was written to ensure that appeals would be rare. She said the eligibility requirements are so clearly defined that disputes about whether someone meets them would be unusual and most applicants would need limited assistance, if any, from attorneys.

Stephen Pina and when DAs dig their heels in

“There is not enough money the commonwealth can give me or any of my brothers and sisters,” Stephen Pina told lawmakers at the hearing. “They’ve taken the ability for me to watch my son be born, to hold him, to comfort him when he wakes up from a bad dream, to watch his first steps, to watch my son graduate from middle school, high school, and college.”

Pina spent 28 years in prison for a murder he said he did not commit. In February, a judge overturned Pina’s conviction, finding that prosecutors failed to turn over evidence pointing to a different suspect. Pina is not presently eligible for compensation because the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office is appealing the judge’s ruling.

Pina asked lawmakers to think about the time they spent raising their own children. “I say that’s priceless,” he said. “Priceless.”

And yet, to compensate someone for the harm caused by a wrongful conviction, a price must be set. Under the proposed legislation, victims would be eligible for $115,000 per year of wrongful incarceration and “not less than” $57,500 for each year of wrongful parole or probation or for each year the person was wrongfully required to register as a sex offender. The total would also be adjusted for inflation, but only if it resulted in a higher amount.

Under the current law, victims can obtain up to $1 million plus legal expenses, regardless of how many years they were incarcerated. To reach a settlement with the AGO, a victim generally must negotiate a lower amount and often must pay their legal expenses out of their settlement. The proposed law would entitle exonerees to more money than the current $1 million cap if they spent more than 8.7 years in prison.

“The cap is grossly regressive,” Beckman told lawmakers. “The longer a person has suffered wrongful imprisonment, the less amount they get per year in compensation. Our state can do better.”

The significance of compensation for parole as well as prison time served

In an interview for this article, Beckman of the Boston College Innocence Program said the fact that the bill would allow people to be compensated for time spent on parole would also make a big difference for some victims. She said one of her former clients, Milton Jones, was wrongly convicted of murder and spent 15 years in prison followed by more than 30 years on lifetime parole.

“He wasn’t eligible for any compensation for all of those years [he was on parole],” she said. “I guess it’s better than being in prison, but there’s significant restrictions on your liberty and your dignity, and you’re navigating through life still bearing the label ‘convicted murderer.’”

Asked whether $115,000 per year of wrongful incarceration was enough, a spokesperson for the AGO said: “While no dollar figure can adequately capture the harms of wrongful incarceration, the dollar figure proposed in the bill was developed in consultation with the innocence bar, attorneys who represent those who have been wrongfully convicted. And when combined with the lifting of the current cap on damages, would result in higher compensation in many instances as compared with current law.”

Jehlen, the senator who filed the bill, also said no amount of money would ever be enough to compensate someone for years of wrongful incarceration. But Jehlen said she believes in her bill because it’s received approval from exonerees, innocence lawyers, and the AGO.

“This is an amount that will keep people from arguing longer about and getting negotiated down because they’re desperate,” she said.

However, Loevy-Reyes, the Boston-based litigator, called the amount of compensation the bill would provide “woefully inadequate.”

“It’s a fraction of what juries tend to give in wrongful conviction cases, so I definitely think that the compensation amount to actually do justice should be considerably higher,” he said.

Wrongful conviction compensation fairness and seeking damages above the cap

Since the current version of the state compensation law took effect in 2018, victims who reached settlements with the AGO received an average of $645,750. Only a quarter of these settlements resulted in the maximum amount of $1 million.

In contrast, four victims have obtained jury verdicts in their favor—and in all but one of those cases, the jury awarded substantially more than $1 million. One of Loevy-Reyes’s clients, Fred Weichel, spent 36 years in prison for a murder conviction that a judge overturned in 2017. The AGO, which at the time was headed by Healey, opposed Weichel’s compensation claim. In 2022, a jury sided with Weichel and awarded him $33 million—nearly $1 million per year he was in prison. However, the state was only required to pay Weichel $1 million plus legal expenses due to the cap.

In 2018, a jury awarded $5 million to Kevin O’Loughlin, who testified that he was threatened and beaten during the four years he spent in prison after he was wrongfully convicted of child rape. And in 2024, a jury awarded $13 million to Michael Sullivan, who spent 26 years in prison for a wrongful murder conviction. Like Weichel, their payouts were slashed to $1 million. The only victim to whom a jury awarded less than the cap was Michael Fortune. He spent a year-and-a-half in prison for breaking and entering and larceny convictions that were overturned on appeal, according to court records. In May, a jury awarded him $750,000.

The four jury verdicts add up to $51,750,000. That’s nearly twice the total amount of money the state has paid to all 60 people who have received compensation under the statute since it was first enacted in 2004.

Wrongfully convicted people can also file federal civil rights lawsuits, which do not have a cap and can result in much larger payouts than the state law. Weichel reached a $14.9 million settlement with Braintree in September. Albert Brown is currently pursuing his own federal suit against Boston. But as with state compensation claims, federal lawsuits can take years to resolve. Sean Ellis—who reached a $16 million settlement with Boston in 2021—told lawmakers that “having to fight through additional litigation in order to be compensated further perpetuated [his] trauma.”

And according to Loevy-Reyes, federal suits aren’t always an option for wrongfully convicted people. Unlike the state compensation law, he said, winning a federal civil rights case requires proving that government officials deliberately committed misconduct. He said federal courts have also created legal doctrines that shield officials from liability, including qualified immunity.

“It’s like an extra hurdle to actually get to a verdict in federal civil rights cases,” Loevy-Reyes said. “Qualified immunity basically shields misconduct if the courts can say that the [police] officer didn’t know any better.”

He added that prosecutors are almost always immune from civil rights suits for their actions related to prosecutions, even when they have committed misconduct. That means the state compensation law can be the only way to hold the commonwealth accountable, even when it’s possible to sue municipalities and local police in federal court. He said that despite the state compensation law’s flaws, it’s “fantastic” that the state has such a law at all “because not all states do.”

For Beckman, the specific amount of compensation that exonerees receive is less important than having a system that provides meaningful compensation sooner.

“Money cannot restore the past, and it cannot wipe out the reputational harm that wrongly convicted people have suffered,” Beckman said. “That is not the goal—that’s impossible. The goal is something more modest, and it’s to replace what is an unfair, inadequate, and inefficient status quo with a method that gets some transitional assistance and compensation to exonerees so that they can have a chance to rebuild their lives.”

This article is syndicated by the MassWire news service of the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism.

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t seen it yet, please check out my reporting on James Carver, who spent 36 years in prison until a judge recently overturned his arson and murder convictions.

“They took my life away for nothing.”

James Carver spent 36 years in prison after he was convicted of setting one of the deadliest fires in Massachusetts history. But after reviewing new scientific evidence, a judge set him free.

The Essex County District Attorney’s Office is appealing the judge’s ruling. The DA’s Appeals Court brief was originally due on June 23. However, the court granted a request for an 87-day extension, so it’s unlikely there will be any updates about the case until September.

As always, if you’d like to keep The Mass Dump running, please consider offering your financial support, either by signing up for a paid subscription to this newsletter below, becoming a Patreon supporter, or sending a tip via PayPal or Venmo. It takes a tremendous amount of work to bring you stories like this, and I rely on your support to keep doing it. A monthly subscription is just $5!

Even if you can’t afford a paid sub, please sign up for a free one to get updates about this story, and please share this article on social media.

You can follow me on Bluesky and Mastodon. You can email me at aquemere0@gmail.com.

That’s all for now!