Judge Hears Arguments About Whether to Overturn Man’s 34-Year-Old Murder Convictions

James Carver was convicted of setting a fire that killed 15 people — but his lawyers say they have scientific evidence that proves he is innocent

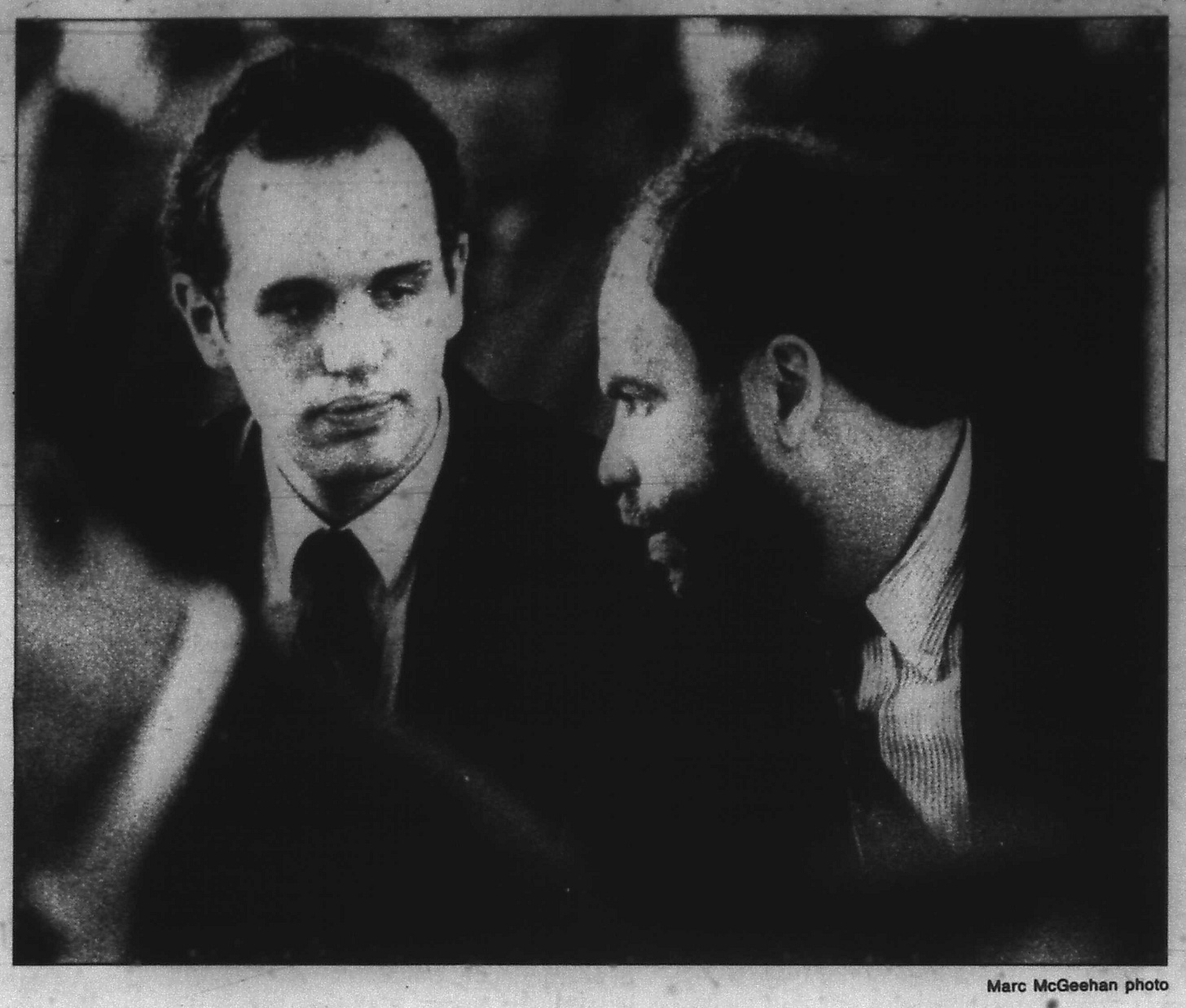

The deadly 1984 Elliott Chambers Rooming House fire in Beverly was described as the “worst mass murder in Massachusetts history” by The Beverly Times after officials said it was a case of arson. And in 1989, a young man named James “Jimmy” Carver was convicted of murdering the 15 people who were killed by the inferno.

But for the past 34 years, Carver has maintained his innocence while serving two consecutive life sentences in state prison. And this past April, his attorneys finally had the opportunity to argue before a judge that his decades-old convictions should be overturned due to new scientific evidence that they say proves he didn’t set the fire.

At the courthouse in Lawrence, Carver’s lawyers spent three days presenting expert testimony from a retired fire-safety engineer who said that the prosecutor’s theory of how the blaze started was physically impossible.

One of the attorneys, Lisa Kavanaugh, said during her closing argument on the fourth day of the hearing that the new testimony proves Carver was wrongfully convicted and is entitled to a new trial.

In Massachusetts, a judge “may grant a new trial at any time if it appears that justice may not have been done,” according to the state’s rules of criminal procedure. Lawyers must either present important evidence that was not available at the time of the original trial or show that the defendant’s trial lawyer was unusually ineffective.

During the 1989 trial, a prosecutor argued that Carver started the fire by pouring gasoline on a bundle of newspapers and burning it in the rooming house’s entrance because he was angry his ex-fiancee dated a man who lived in the building. An arson investigator testified that he observed charring on the walls outside the doorway that could have only been caused by a fire started with a flammable liquid like gasoline.

But during the hearing in April, expert witnesses for both Carver and the district attorney’s office said the testimony was based on a discredited myth and there was actually no physical evidence a flammable liquid was used.

And the witness presented by Carver’s legal team went further, testifying that it wasn’t possible for the newspapers to have generated a flame powerful enough to have spread to the building. He said the fire’s true cause can’t be determined based on the available evidence and that he couldn’t rule out accidental causes like an electrical malfunction.

Catherine Semel, an Essex County assistant district attorney, acknowledged that the arson investigator gave scientifically invalid testimony in 1989. However, Semel argued that Carver was not entitled to a new trial because there was still enough evidence to prove his guilt and because some of the engineer’s testimony was not based on new science.

A spokesperson for Essex County District Attorney Paul Tucker did not respond to a request for comment.

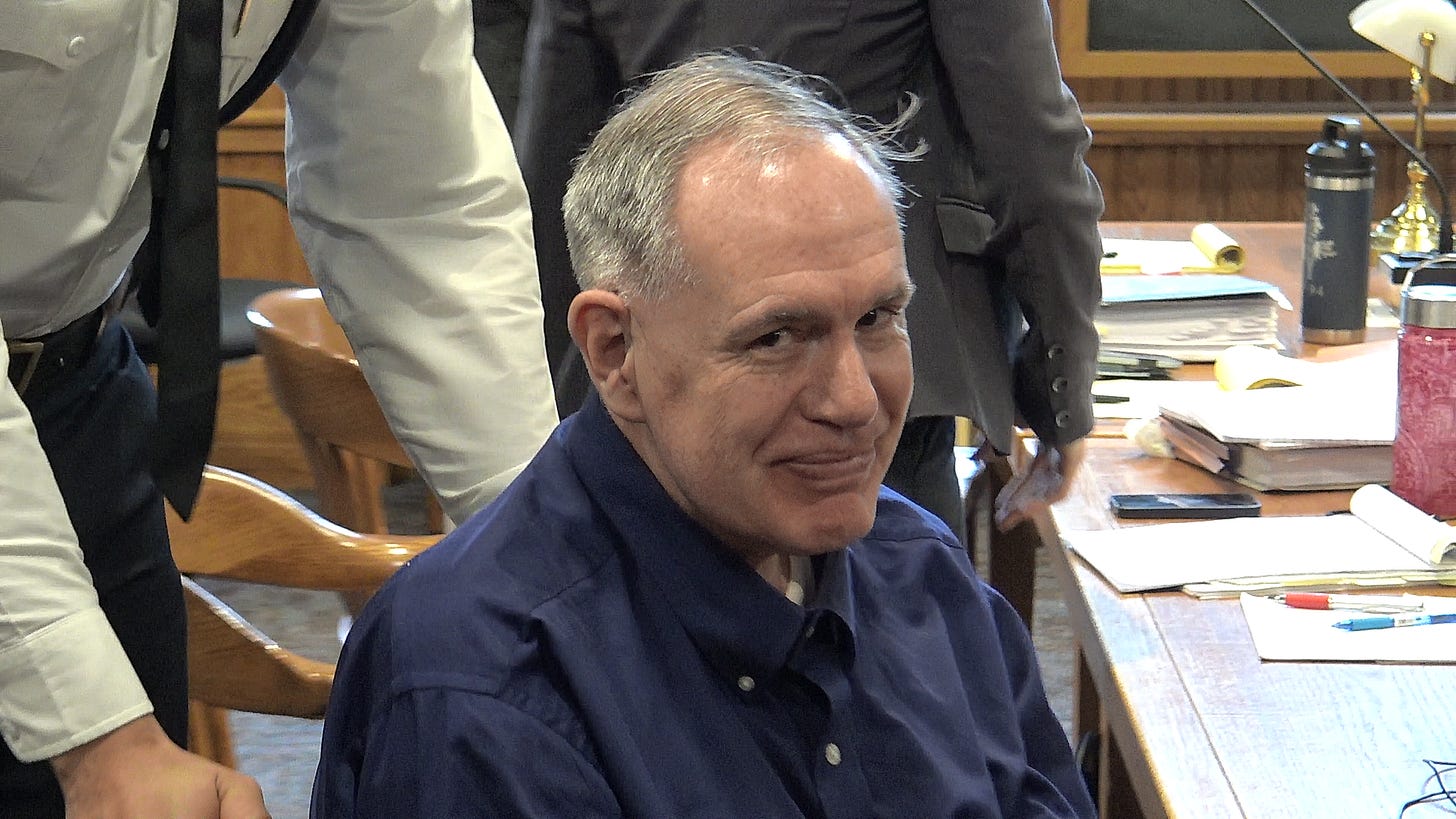

Carver, who is now 60, has difficulty standing and requires a wheelchair to get around due to a 2005 surgery to remove a brain tumor, according to court documents.

He listened to the proceedings with headphones because he is hard of hearing. His wrists and ankles were shackled throughout the proceedings.

Carver has been represented by Kavanaugh and another attorney, Charlotte Whitmore, since 2019.

Kavanaugh is the director of the innocence program at the state’s public defender office, the Massachusetts Committee for Public Counsel Services. Whitmore is a staff attorney at the Boston College Innocence Program.

The lawyers’ March 2022 motion for a new trial is Carver’s fifth attempt at overturning his conviction. However, it is the first attempt by his current legal team — and the first attempt to use scientific evidence to challenge the prosecution’s theory that the fire was arson.

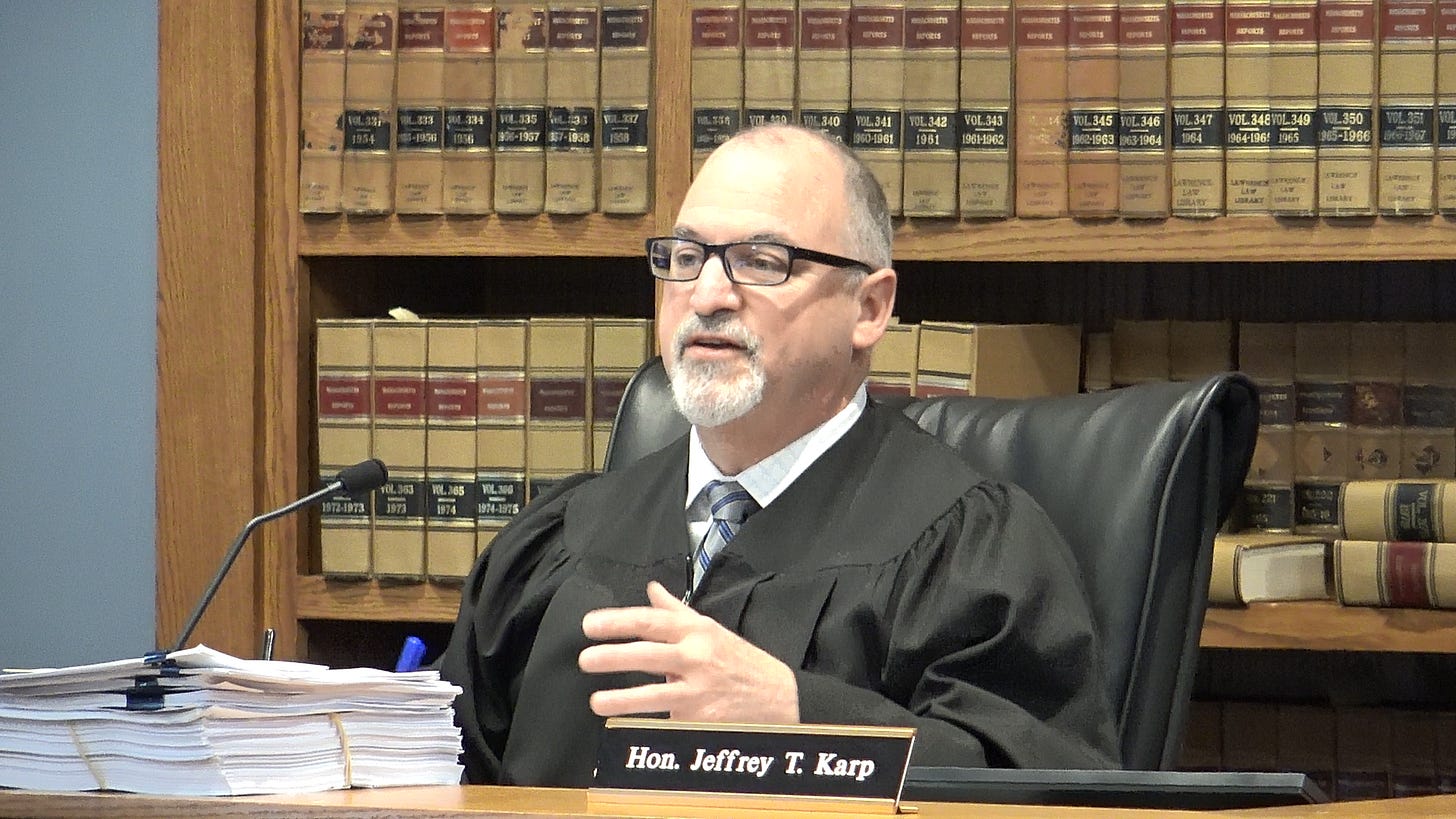

Essex County Superior Court Judge Jeffrey Karp, who presided over the hearing, held closing arguments on April 12. The judge listened attentively and often interjected with questions.

Semel argued for the district attorney’s office first and was followed by Kavanaugh.

“This is an almost 40-year-old case,” Semel began. “And when a defendant delays in bringing a motion for a new trial for a number of years, the fading of memories, gaps in the evidence, … these weigh against the defendant. It’s still his burden.”

Semel said that for Carver’s conviction to be overturned, he must show there’s a “substantial risk the jury would have reached a different conclusion” and that he hasn’t done so.

Semel said a witness testified that Carver confessed to setting the fire by pouring gasoline on newspapers and burning them, which is strong evidence of his guilt.

But Kavanaugh said the witness’s testimony was unreliable because the alleged confession contradicted the physical evidence of how the fire started.

Kavanaugh began by saying Judge Karp’s role is not to decide whether Carver would have been acquitted had he been able to present the new evidence. Weighing the evidence is the jury’s responsibility, she said, so the judge’s role is only to determine whether the new evidence would have impacted jury’s deliberations.

“Evidence that … would probably have been a real factor in the jury’s deliberations, by definition, cast[s] doubt on the justice of the conviction,” she said.

Carver thought the hearing went well but was anxious due to uncertainty about how the judge will rule, according to his younger brother.

“He’s anticipating the decision and also dreading it at the same time because we just don’t know which way it’s going to go,” said Bill Carver, the brother.

Bill Carver said he couldn’t attend the hearing because he lives in Michigan and is being treated for kidney cancer. However, he watched a recording of the closing arguments and thought the judge seemed “verifiably interested in the case.”

“I’m kind of a religious guy,” he said. “I’m praying … for wisdom on the judge’s part and for, quite frankly, fairness.”

Investigative journalism like this takes a ton of time, energy, and care. Please consider signing up for a paid subscription to The Mass Dump newsletter below, becoming a Patreon supporter, or sending a tip via PayPal or Venmo to make more work like this possible.

“There’s a Simple Answer”

Kavanaugh said the most important new evidence was the expert testimony that there was no proof a flammable liquid was used to start the fire.

“There’s a simple answer, which is that Mr. Carver is entitled to a new trial merely on the basis of the newly discovered evidence related to accelerant [use],” she said.

A state chemist who testified at James Carver’s 1989 trial said lab tests did not detect any traces of flammable liquids on samples of the newspapers or concrete and wood taken from the alcove where the papers were found.

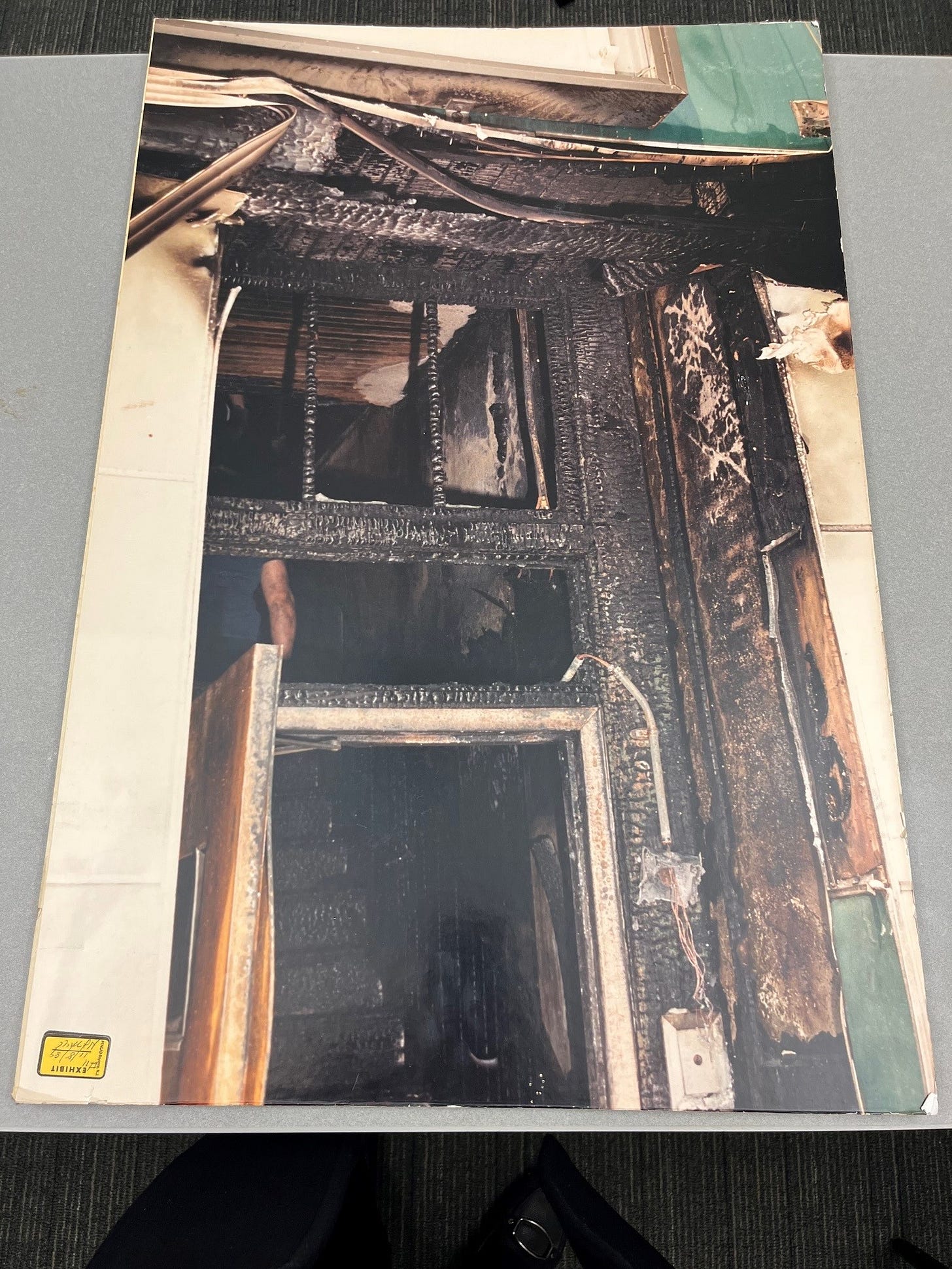

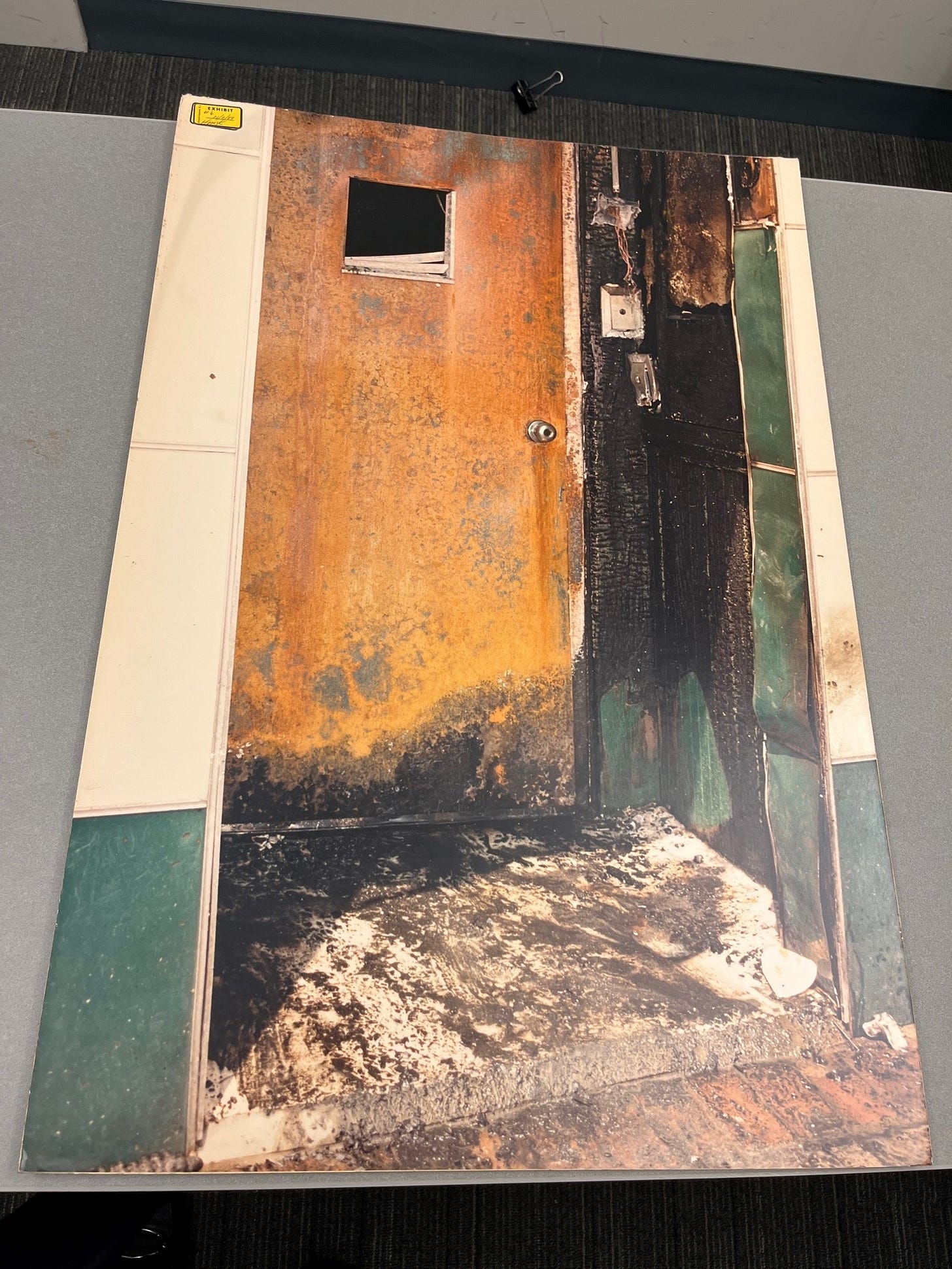

But the arson investigator testified that he observed “alligator charring” blisters — which are named after their resemblance to scaly skin — on the walls of the alcove containing the rooming house’s entrance. The investigator, who is now deceased, said these markings were definitive proof that the fire was started with a liquid accelerant like gasoline.

However, at the April hearing, the investigator’s testimony was debunked by Craig Beyler, an engineer who reviewed documents and photos related to the Elliott Chambers fire for Carver’s legal team.

Beyler said the investigator’s testimony that “alligator charring” is proof of a flammable liquid is a myth that was commonly cited in the ’80s but has since been rejected by scientists. The fact that the lab tests were all negative meant that the arson investigator’s conclusion was “mere speculation,” Beyler said.

The district attorney’s office presented its own expert witness, Michael Mazza, a retired Massachusetts State Police fire investigator. Mazza was not involved in the original investigation of the fire, but he reviewed the same materials as Beyler.

Mazza said it’s possible the fire was started with a flammable liquid but that it was washed away by the water firefighters used to extinguish the blaze. However, he said he couldn’t conclude that a liquid accelerant was used because there was no proof.

Mazza nevertheless defended the arson investigator’s conclusion that the fire was started by someone burning the newspapers. It was possible, he said, for the fire to have started on the newspapers without the use of an accelerant.

But in 1989, the arson investigator testified that a person could not have ignited bundled newspapers without an accelerant, comparing it to trying to light a log on fire.

Kavanaugh said that because the district attorney’s office changed its theory of the case by now claiming that the fire could have started without an accelerant, Carver is entitled to a new trial so that a jury can deliberate on the new theory.

“Trooper Mazza’s testimony was so significantly different from the fire evidence that was presented to the jury at trial … that there’s no question this would have been a real factor in the jury’s deliberations,” she said.

During the trial, the prosecutor said that the fire was started using an accelerant during both his opening statement and closing argument, telling the jury there was “no question” the blaze was arson.

The prosecutor, who is now retired, used the expert testimony about the purported accelerant to corroborate Carver’s alleged confession that he started the fire using gasoline. The prosecutor told the jury that Carver kept a gas can in his car for landscaping work and used it to set the fire. He also repeated the investigator’s comment about bundled newspapers being like a log.

Carver’s trial lawyer, who is now deceased, conceded that the fire was arson during his opening statement and closing argument. The defense attorney instead focused his efforts on proving that Carver was sleeping at his home in Danvers when the fire started and that someone else set it.

Kavanaugh said that the trial lawyer had no reason to challenge the arson theory because the alligator-charring myth was widely accepted in 1989. This meant that Carver was deprived of an important defense, she said.

Semel, the assistant district attorney, argued that the new science debunking the arson investigator’s trial testimony wasn’t significant because there was no definitive proof that an accelerant wasn’t used.

Semel also said that the accelerant testimony didn’t play a major role in Carver’s conviction because he was charged with second-degree murder, which didn’t require the prosecutor to prove premeditation.

“I think that the fact that premeditation wasn’t on the table in this case may have impacted the lack of emphasis by our office on whether or not an accelerant was used,” she said. “It really wasn’t a central point for the Commonwealth.”

But Kavanaugh said the prosecutor emphasized the testimony about accelerant use and that it was crucial to his case.

“I mean, this is an arson case in which the jury is repeatedly told there’s no way this fire started without an accelerant, which is essentially saying there’s no way this fire could have started accidentally,” Kavanaugh said.

“The Heart of the Case”

Kavanaugh said that the science about accelerant use was just one piece of new evidence and that the testimony from Beyler, the fire-safety engineer, called the prosecution’s entire theory of how the fire started into question.

Beyler testified that the fire could not possibly have started on the newspaper bundle. Scientific testing has shown it would take a flame that’s more than four feet high to spread to wooden walls in a corner, he said. A newspaper bundle, he said, would be difficult to set on fire and would produce a flame so small it would be incapable of spreading.

Beyler said he determined the fire did not start at ground level but instead started in the overhang of the alcove where the newspapers were found. He came to this conclusion, he said, because the damage to alcove’s walls was “pretty superficial” while the damage to the overhang was “vastly larger than that.”

The arson investigator documented the charring on the walls as being a quarter-inch deep but the overhang was burned so significantly that pieces of the ceiling were missing, Beyler said.

The damage to the walls and the newspapers could have been caused by a “drop-down fire,” which is when fire is spread by flaming debris that falls from a higher level of a structure to a lower one, he said.

Beyler said there wasn’t enough evidence to conclude what caused the fire but that he could not rule out electrical causes.

There were wires hanging in the alcove after the fire, he said, and investigators did not properly examine the wiring or the building’s electrical system. He also said that investigators didn’t consider the possibility that a light was attached to the missing portion of the ceiling before it was destroyed by the fire.

Mazza, the expert witness for the district attorney’s office, testified that the wires in the alcove were capable of starting a fire but that he thought it was unlikely.

He said the newspaper-fire theory was supported by photographs showing unburned green paint on the lower portion of the walls in the right-hand corner of the alcove. This area, he said, was protected from the fire because the newspaper bundle was wedged in the corner.

Mazza said he was able to use the shape of the unburned area to determine that the newspaper bundle was propped up on its side rather than lying flat. He said that someone ignited the side of the bundle, which would be easier than trying to set fire to the top.

The fire would have grown more intense, Mazza said, because the bundle was placed in a corner and because the walls and ceiling of the alcove would have contained the heat and smoke.

Mazza said that he did not cite any studies or conduct any tests to support his theory that the newspapers could have caused the fire.

Semel said that Carver’s trial lawyer would not have challenged the arson theory even if the new expert testimony had been available in 1989 because the evidence that the fire was arson is so strong.

She said the trial attorney focused on arguing that Carver had an alibi and that someone else set the fire because it was a stronger defense. Arguing that the fire wasn’t arson, she said, would have contradicted the argument that someone else was responsible.

Testimony showing that someone moved the newspaper bundle to the rooming house’s entrance before the fire started was powerful evidence that it was arson, Semel said.

A delivery driver testified that he dropped off the newspaper bundle outside the entrance of the drugstore on the first floor of the Elliott Chambers building, but a firefighter testified that he found the bundle outside the rooming house’s entrance during the blaze.

“Any attempt to challenge whether or not this was an arson was always going to be met with … the coincidence [that] somebody at 4 o’clock in the morning moved those newspapers at the same time that an electrical fire started overhead, coincidentally, and dropped down,” Semel said. “It’s a stretch.”

She said that Carver’s trial attorney consulted with a chemist about the lab tests that found no traces of an accelerant in the alcove. The chemist did not testify, but the consultation showed that the defense attorney considered challenging the arson theory and chose not to do so, she said.

Kavanaugh said the chemist could not have disputed the arson theory because he was not consulted about potential electrical causes of the fire and because the science debunking the alligator-charring myth wasn’t available at the time.

“Everyone [was] operating under the same set of myths and misconceptions,” she said. “That’s guiding not only how the trial was conducted, but how the pre-trial investigation was conducted.”

Kavanaugh said it doesn’t make sense to conclude that Carver’s trial attorney would not have challenged the cause of the fire simply because he had other defenses available.

She said that arguing the fire was not arson is a much stronger defense than arguing someone else set it because the trial attorney had very little evidence pointing to another possible culprit. And challenging the arson theory, she said, does not contradict Carver’s alibi defense.

“I think this puts the fundamental question, was this an arson, right at the heart of the case,” Kavanaigh said. “That [theory] that was accepted by the defense at trial is suddenly at issue and suddenly at play … and that changes everything.”

Kavanaugh said the hearing itself was evidence the trial would have played out differently had the new expert testimony been available in 1989.

“All of the questions that all of us posed to the experts illustrate the kind of deliberations that you would imagine the jury might have if they had this information,” she said.

“The Confluence of Factors”

During the arguments, Judge Karp struggled over the questions of which evidence could be considered “newly discovered,” whether he should consider evidence that wasn’t new, and what significance he should give to the expert testimony he heard.

Karp asked Semel whether he should speculate about whether the outcome of the trial would have changed if jurors had heard the new expert testimony.

“I’ve puzzled over this same question,” Semel responded. “And I think that one way to look at it would be to just look at the trial testimony, take out the offending [testimony], … and look at what the trial would have looked like.”

She said Karp should consider how the trial would have played out if the arson investigator had not been allowed to testify that there was conclusive evidence an accelerant had been used to start the fire.

However, she argued that Beyler’s other testimony about the origin and cause of the blaze wasn’t based on new science.

“That’s not newly discovered evidence,” Semel said. “It’s a different opinion, and I would suggest it shouldn’t be considered the same way if it’s considered at all.

She said Carver waived the right to present expert testimony about the fire’s origin and cause to a jury because his trial lawyer didn’t call an expert witness in 1989.

Kavanaugh told Karp that he should consider all of the expert testimony, whether or not he determined it was based on new science. When new evidence becomes available, she said, it can put old evidence in a new context that makes it worth reexamining.

She said that Karp should not consider the new evidence about accelerant use “narrowly.” Instead, she said, the judge should ask himself, “What is the totality of the picture?”

She said that Karp should use the “confluence of factors” approach, which Massachusetts courts have relied on when reviewing new-trial motions in recent years. Under this approach, even if one issue isn’t sufficient to warrant a new trial, a judge can consider how the relationship between multiple issues can cast doubt on the integrity of a conviction.

“So in other words,” Kavanaugh said, “we have the newly discovered evidence, but even if the court were to rule that that isn’t enough, you can consider it in tandem with all of these other pieces of evidence.”

Karp asked Kavanaugh what he should do if he determined that parts of Beyler’s testimony weren’t credible.

“The issue of credibility is for a jury and not the judge,” Kavanaugh said. “What the court says is, if you’ve got admissible expert testimony, it’s for the jury to decide how much weight [you] need to give [it].”

“Overwhelmingly Clear That Justice Was Not Done”

Semel said testimony from one trial witness, who said she was a former friend of Carver and that he confessed to setting the fire, was such strong evidence of guilt that he was not entitled to a new trial.

“Here we had really a lot of evidence, a lot of it from the defendant’s own mouth, which I think is also significant,” Semel said.

The former friend testified that Carver invited her to his home in October 1984 and made a tearful confession. According to the witness, Carver said that he set a fire by pouring gasoline on newspapers and burning them with a match.

Kavanaugh said the new scientific evidence contradicts the alleged confession. She pointed to Beyler’s testimony that the fire started in the overhang and could not have started on the newspapers.

“It’s easy to imagine how much more effectively the defense would have been able to discredit [the witness] if he’d been able to point out that, at least according to his expert, the fire did not start the way that Mr. Carver allegedly admitted to,” Kavanaugh said.

The witness acknowledged in her testimony that she never went to the police after Carver allegedly confessed to her. Instead, she said, investigators called her in March 1987 after she moved to New York, and she then told them about the alleged confession for the first time.

After Carver was arrested in May 1988, Kevin Burke, who was the Essex County district attorney at the time, said that the witness’s statement to police was what finally made it possible for his office to file charges, according to news reports.

Most of law enforcement’s theory of how the fire started was widely publicized long before the witness told police about the alleged confession. Just one day after the July 1984 blaze, officials told the media that they believed someone deliberately started it by burning a bundle of newspapers in the rooming house’s entrance, although they did not mention gasoline or a liquid accelerant, according to news reports.

Carver’s trial lawyer did not dispute that Carver made the alleged confession. Instead, the attorney said during his closing argument that Carver “was crying out for help” because he had been under investigation for months, was the subject of constant rumors, and “just couldn’t bear being accused of this any more.”

Carver had been drinking, was extremely emotional, and said he wanted to kill himself when he made the alleged confession, according to the witness’s testimony. Carver said that he didn’t mean to hurt anyone and was only trying to scare his ex-fiancee and the man she had dated, the witness said.

“Everybody was believing he did it,” the trial lawyer said. “Nobody was saying he didn’t do it. Put yourself in his shoes. When you are accused of something repeatedly, doesn’t it get a lot easier just to say: Yeah, I did it?”

Semel said this was a reasonable strategy for the defense attorney to pursue based on the evidence.

“I have to tell you, I cringed when I read that in the closing,” Karp said. “[Arguing that] somebody … would seek to curry sympathy … by admitting that he killed 15 people smacks as a desperate thing to say.”

“Well,” Semel responded, “he certainly, according to [the witness], did it in a remorseful way. … He felt bad about it.”

Karp asked Kavanaugh why someone would confess to setting the fire.

“I think that’s certainly a question that the jury might still wrestle with,” Kavanaugh said. “But the question that this court has to resolve is would that wrestling look different if [the jury heard the new expert testimony].”

She said it should be up to a jury to determine whether the new testimony impacts the credibility of the alleged confession.

Karp hinted that he might agree.

“I do believe that [the accelerant evidence is] a significant factor, because, again, it ties into this so-called confession,” the judge said. “And we can never read an attorney’s mind … about what they would have done differently. But isn’t the point what the jury would have done?”

“Absolutely,” Kavanaugh said.

Semel ended her argument by encouraging Karp not to consider all the testimony presented at the hearing.

“Even with the confluence of factors, especially with a case of this age, that doesn’t necessarily mean that everything that the defendant wants to present gets considered and nothing is waived,” she said.

Kavanaugh ended her argument by returning to the theme of justice.

“It’s our position that … it is overwhelmingly clear that justice was not done, that Mr. Carver is entitled to a new trial,” she said. “Whether Your Honor focuses solely on the accelerant or takes the broader view of looking at the accelerant in connection with the other newly discovered and the other newly presented evidence.”

This story is the third part of a series about the James Carver hearing. You can read the first part, which focuses on problems with eyewitness testimony from Carver’s trial here. You can read the second part, which provides more details about the expert testimony about the fire’s origin and cause, here.

In the near future, I’ll be publishing a fourth piece about the final day of the hearing in May, which focused on documents related to Carver’s trial lawyer. Carver’s current lawyers say that the trial lawyer failed to act on an important piece of evidence and was addicted to cocaine and alcohol while working on the case. This part of the hearing happened after closing arguments because there was no new testimony related to these issues, only legal arguments about which documents were admissible and what their significance is.

Hopefully I’ll get this piece out next Monday, but there might be a delay due to a death in my family.

Again, if you’d like to keep The Mass Dump running, please consider offering your financial support, either by signing up for a paid subscription to this newsletter below, becoming a Patreon supporter, or sending a tip via PayPal or Venmo. It takes a tremendous amount of work to bring you stories like this, and I rely on your support to keep doing it.

Even if you can’t afford a paid sub, please sign up for a free one to get updates about this story, and please share this article on social media.

You can follow me on Facebook, Twitter, Mastodon, and Bluesky. If you have any information about the Elliott Chambers fire or the James Carver case, please email me at aquemere0@gmail.com.

Anyway, thanks for reading! That’s all for now.