Judge Overturns Convictions of Man Accused of Setting Deadly 1984 Beverly Rooming-House Fire

For decades, James Carver has maintained that he is innocent of setting a fire that killed 15 people — and now he is again innocent in the eyes of the law

As James “Jimmy” Carver sat in his wheelchair and looked at his two attorneys, he knew something was up. Usually the lawyers had visited him in prison separately. But on Christmas Eve, they appeared together, in person, and without warning.

“Is it good news?” Carver asked.

In 1989, Carver was convicted of setting a horrific fire that killed 15 people and sentenced to life in prison — but for 35 years he maintained his innocence, and during that visit, he learned that he is once again innocent in the eyes of the law.

On December 23, Essex County Superior Court Judge Jeffrey Karp overturned Carver’s convictions for arson and 15 counts of second-degree murder, writing that advances in the science of fire and eyewitness memory undermined key evidence presented at trial and “cast real doubt on the justice of” the guilty verdicts.

The following morning, Carver’s lawyers, Lisa Kavanaugh and Charlotte Whitmore, told him about the ruling.

“Mr. Carver was overwhelmed with emotion, fighting through tears of joy to express his gratitude,” the lawyers said in a statement. “We are thrilled that Mr. Carver has some relief after well over three decades of wrongful incarceration.”

Kavanaugh is the director of the innocence program at the state’s public defender agency, the Massachusetts Committee for Public Counsel Services. Whitmore is a staff attorney at the Boston College Innocence Program.

During a five-day hearing in April and May, Kavanaugh and Whitmore presented testimony from a retired fire-safety engineer who said that the prosecutor’s theory of how the blaze started was physically impossible and that he couldn’t rule out accidental electrical causes. The lawyers also presented testimony from a psychologist, who said that an eyewitness’s identification of Carver was scientifically unreliable.

The new evidence upended a 40-year-old narrative about one of the state’s deadliest fires. When a brutal blaze tore through the Elliott Chambers Rooming House in Beverly, officials immediately concluded it was a case of arson. The Beverly Times described the 1984 fire as the “worst mass murder in Massachusetts history” — but the engineer testified that there is no physical evidence it was deliberately set.

Karp ruled that the testimony from the expert witnesses is new evidence because it’s based on scientific research that was not available in 1989 when Carver was tried and that this evidence is strong enough to warrant granting Carver a new trial.

Members of Carver’s family were elated when they heard about the ruling — including his daughter, Kaitlyn Verzi, who was born less than two months before he was arrested.

“My family finally is going to be a family again,” Verzi said. “All the patience, and waiting, and the fighting for him, and everything — it finally worked. So [I] may not have [had] him when I was a kid, but my kids will get to have him.”

Carver remains in prison while his lawyers and the Essex County District Attorney’s Office work to schedule a bail hearing — and as a result, Verzi said she has mostly been reserved since her initial reaction.

“I’ve always kind of had good news and then it gets ripped away,” she said. “I do know that it’s like 95-percent set in stone … but there’s still that little percentage where I’m like, Okay, I’m going to hold off on my celebrations until I’m holding my dad in my arms outside the walls of the prison.”

The district attorney’s office, which opposed Carver’s effort to overturn his convictions, has 30 days from the date of Karp’s ruling to decide whether to appeal. The office also has the option to prosecute Carver again, although many of the original investigators and other witnesses have died and important pieces of evidence have been discredited.

“We are carefully reviewing the ruling and exploring options,” Essex County District Attorney Paul Tucker said in a written statement. “We are also attempting to locate and notify the families of the 15 victims who were killed in the fire.”

Robert Weiner, the now-retired assistant district attorney who prosecuted Carver, did not respond to a request for comment.

Verzi said she hopes that she can eventually build an addition to her home so that her father can live with her and her family, but she said that he will likely need to stay in an assisted-living facility for the time being due to his complex medical needs.

During his decades in prison, the now-60-year-old Carver has developed a number of health issues, according to court records.

He had surgery to remove a brain tumor in 2005 and as a result is incontinent, has difficulty standing, and requires a wheelchair to get around, the records say. He also experiences tremors, requires assistance getting dressed and eating when they occur, and is deaf in one ear and hard of hearing in the other, according to the records.

Verzi said her father also lost family during his time in prison. Carver’s parents are both deceased, and his older brother died this year, she said.

His parents, Roger and Gail Carver, paid for his trial attorney and lost their Danvers home to foreclosure in 1992 due to the legal bills. During his trial, both testified that he was asleep at home when the fire started.

The first thing Carver wants to do after getting out of prison, Verzi said, is visit the cemetery where his parents and brother are buried.

Investigative journalism like this takes a ton of time, energy, and care. Before you finish reading this story, please consider signing up for a paid subscription to The Mass Dump newsletter below, becoming a Patreon supporter, or sending a tip via PayPal or Venmo to make more work like this possible.

“It Is An Understatement”

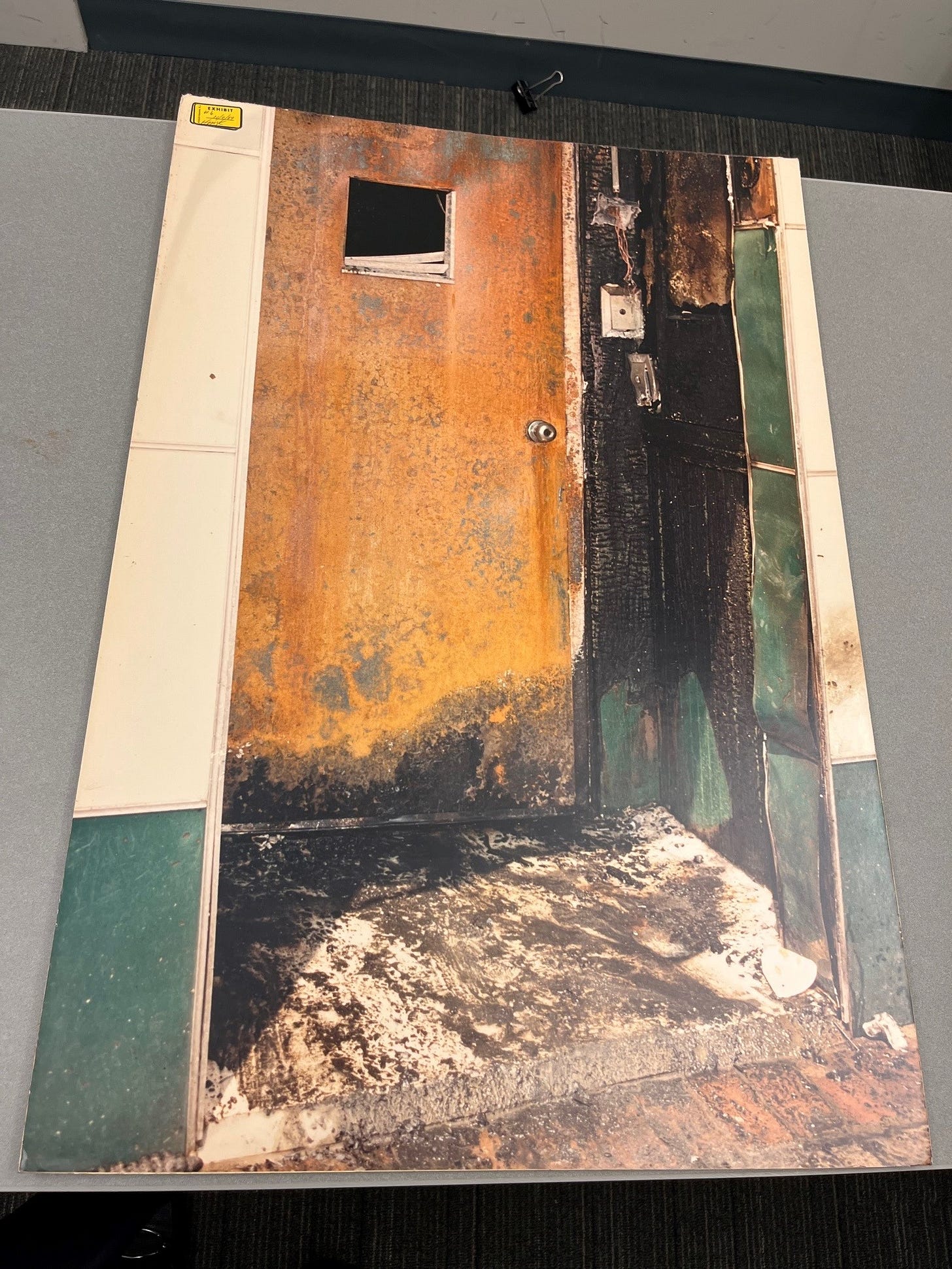

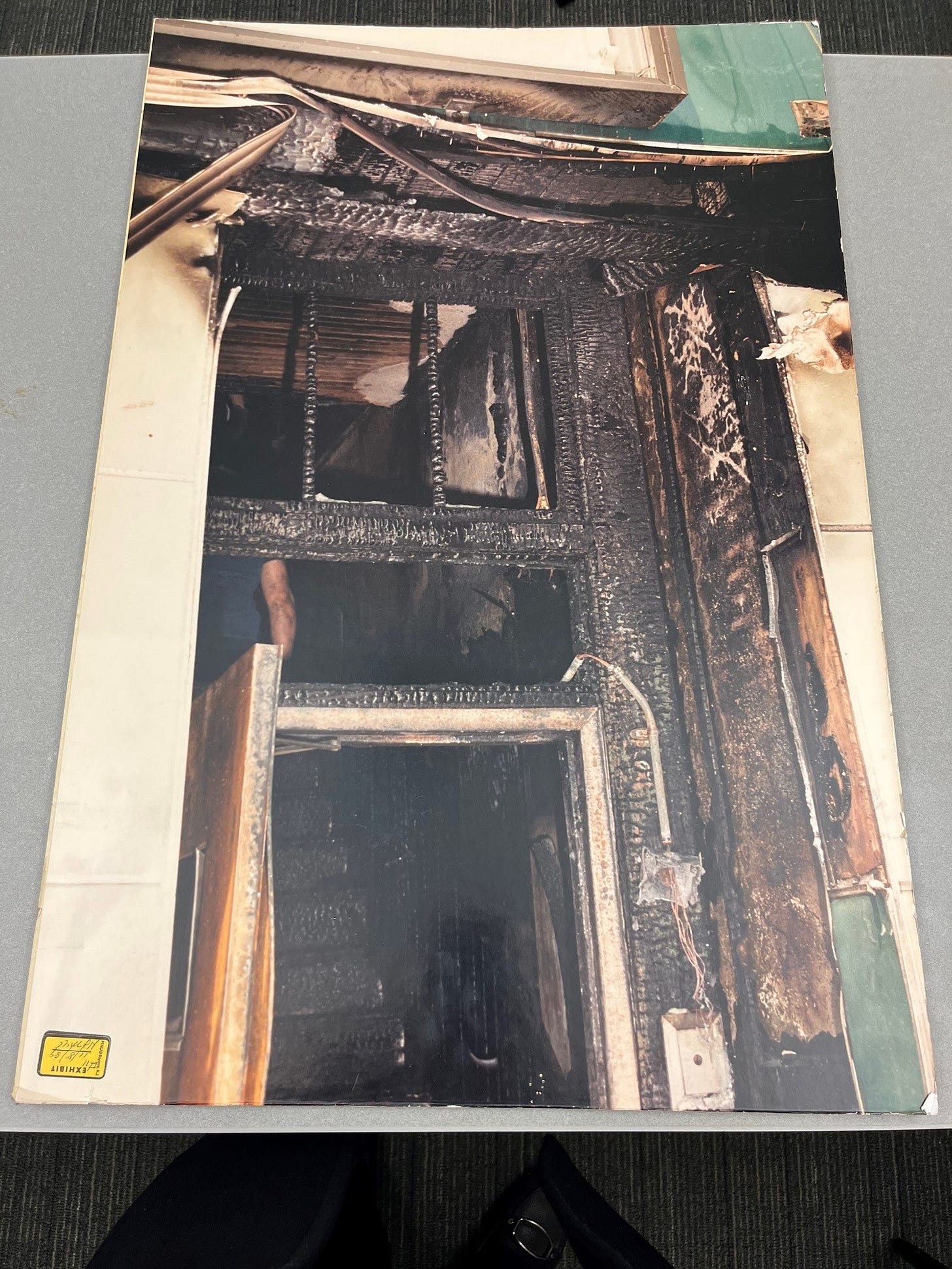

During the 1989 trial, the prosecutor, Weiner, argued that Carver started the fire by pouring gasoline on a bundle of newspapers and burning it in the entrance to the Elliott Chambers because he was angry his ex-fiancee dated a man who lived in the building. An arson investigator testified that he observed charring on the walls outside the doorway that could have only been caused by a fire started with a flammable liquid like gasoline.

But according to Karp’s decision, the investigator’s conclusions were refuted by testimony from expert witnesses for both Carver and the district attorney’s office. At the recent hearing, the expert witnesses said the investigator’s testimony was based on discredited myths and there was actually no physical evidence a flammable liquid was used.

“It is an understatement to say that these and other advances in fire science … undermine the Commonwealth’s sole theory at the trial regarding the origin and cause of the fire,” Karp wrote.

A state chemist who testified at Carver’s trial said lab tests did not detect any traces of flammable liquids on samples of the newspapers or concrete and wood taken from the alcove where the papers were found.

But the investigator testified that he observed “alligator charring” blisters — which are named after their resemblance to scaly skin — on the walls of the alcove. The investigator, who is now deceased, also said he observed “smoke swirling” stains on the walls of the alcove. He said these markings were definitive proof that the fire was started with a liquid accelerant like gasoline.

The investigator also testified that he determined the fire’s point of origin using the idea that fire cannot spread downward. The newspaper bundle must have been the origin, he said, because it was located at the lowest point of burn.

However, at the recent hearing, the investigator’s testimony was debunked by Craig Beyler, an engineer who reviewed documents and photos related to the Elliott Chambers fire for Carver’s legal team.

Beyler said the investigator’s testimony about “alligator charring” and “smoke swirling” was based on myths that were commonly cited in the ’80s but have since been rejected by scientists. The fact that the lab tests were all negative meant that the arson investigator’s conclusion was “mere speculation,” Beyler said. And the idea that fire cannot travel downward, he said, was also false.

At the hearing, the district attorney’s office presented its own expert witness, Michael Mazza, a retired Massachusetts State Police fire investigator who was not involved in the original investigation of the Elliott Chambers blaze.

Mazza said it’s possible the fire was started using a flammable liquid that was washed away when firefighters applied water to the building. However, he said he couldn’t conclude that a liquid accelerant was used because there was no proof.

Mazza nevertheless defended the original investigator’s conclusion that the fire was started by someone burning the newspapers. It was possible, he said, for the fire to have started on the newspapers without the use of an accelerant.

In Massachusetts, a judge “may grant a new trial at any time if it appears that justice may not have been done,” according to the state’s rules of criminal procedure. Lawyers must either present important evidence that was not available at the time of the original trial or show that the defendant’s trial lawyer was unusually ineffective.

Lawyers for the district attorney’s office argued that Beyler’s testimony was just a new opinion about old evidence. However, Karp ruled that because Beyler’s testimony was based on significant advances in science, his opinions were new evidence.

Beyler testified that the fire could not possibly have started on the newspaper bundle. Scientific testing has shown it would take a flame that’s more than four feet high to spread to wooden walls in a corner, he said. A newspaper bundle, he said, would be difficult to set on fire and would produce a flame so small it would be incapable of spreading.

Beyler said he determined the fire did not start at ground level but instead started in the overhang of the alcove where the newspapers were found. He came to this conclusion, he said, because the damage to alcove’s walls was limited while the overhang was so significantly damaged that pieces of the ceiling were missing.

The damage to the alcove’s walls and the newspapers could have been caused by a “drop-down fire,” which is when fire is spread by flaming debris that falls from a higher level of a structure to a lower one, he said.

Beyler said there wasn’t enough evidence to determine the exact point of the fire’s origin or what caused it. He said he couldn’t rule out electrical causes due to the presence of wires in the alcove and the failure of investigators to document the building’s electrical equipment.

In addition to citing the advances in fire science, Karp found that Carver’s conviction should be overturned due to developments in the science of eyewitness memory.

At the 1989 trial, a cab driver testified that he saw Carver at the Elliott Chambers building shortly before the fire started. However, Carver’s lawyers presented testimony from Nancy Franklin, a retired Stony Brook University psychology professor, who said the cab driver’s identification of Carver was unreliable.

Karp said that, because the science of eyewitness memory wasn’t well established in 1989, the jury that convicted Carver couldn’t fully appreciate the unreliability of the cab driver’s testimony.

The cab driver, Karp wrote, was a stranger to Carver. The cab driver picked someone who wasn’t a suspect from a photo array in addition to picking Carver, was shown the same photo of Carver three times before seeing him in a lineup, and was subjected to suggestive comments by law enforcement.

Lawyers for the district attorney’s office argued that the arson investigation and eyewitness testimony weren’t crucial to Carver’s conviction. Carver was not entitled to a new trial, they argued, because he had a motive and allegedly made incriminating statements.

However, Karp said that the trial prosecutor emphasized the fire investigator’s erroneous testimony multiple times during both his opening statement and closing argument. Furthermore, Carver’s alleged motive and the allegations that he made incriminating statements, according to Karp, were not strong enough evidence to warrant maintaining the convictions.

“A Very Great Christmas Gift”

When the court sent out an email about Karp’s ruling on December 23, Whitmore was the first of Carver’s lawyers to see it.

“I was driving,” Kavanaugh said, “and [Whitmore] called me, like, a whole bunch of times in a row.”

When the two finally got on the phone together, they “were both so excited [they] could barely talk,” Whitmore said.

The following morning, the lawyers visited Carver at Old Colony Correctional Center in Bridgewater, where he is incarcerated.

The two planned to arrive at 9 AM, but both had trouble sleeping — Whitmore said she woke up between 4:30 and 5, and Kavanaugh said she couldn’t sleep at all. Kavanaugh said she emailed Whitmore at 6, and the two decided to head to the prison an hour early.

“I brought these silly little Christmas headbands and tried to ask the correctional officers if we could wear them in [the visiting room],” Whitmore said. “And they said no. … But [on] that day, we were just happy to be there.”

After they made it through security, they were able to see Carver in one of the visiting rooms, and he seemed down, Kavanaugh said.

“I took his left hand,” she said, “and told him we had good news to share, and then Charlotte took his right hand as I continued to explain that the judge granted our motion for [a] new trial.”

That’s when Carver started crying.

“You could see the relief, the gratitude,” Whitmore said. “But also the validation or pride in his face that he had been saying this to everybody who would listen for so long, and it was finally getting recognized by the legal system.”

After Carver’s words returned to him, he “said he wished parents had been alive to read this decision, because they stood by him for all those decades of wrongful incarceration,” according to Whitmore.

After the visit, Kavanaugh said, Carver “wheeled himself out of the visiting room, and he had to wait for us to leave before they would process him out the door that he leaves, and we looked back just as we were walking out the door, and he had started crying again.”

After the attorneys left, Carver called his daughter, Verzi, to tell her the news.

Verzi said she woke up to her phone ringing. She answered, she said, and when her father told her that his convictions had been overturned, she had trouble believing it and had to text Kavanaugh to make sure she understood correctly.

“I’ve wished for [this] for all my birthday wishes, my Christmas wishes since I was a tiny little girl,” Verzi said. “And to have that finally coming true is kind of like, Is this real? Can someone pinch me?”

Carver’s younger brother, Bill Carver, said he was in a movie theater when the news broke. He received calls from Verzi and his brother but didn’t answer them, he said. He finally learned the news after receiving a text from this reporter, he said, and wanted to dance in the theater.

“It was a very great Christmas gift to get,” he said.

When the movie ended a few minutes later, he said, he left the theater, called Verzi, and cried. He said he plans to travel from his home state of Michigan to be there when his brother is released from custody.

“Number one, he’s going to need a ride,” Bill Carver said. “And number two, I just want to be there to hold my brother.”

Thanks for reading!

Again, if you’d like to keep The Mass Dump running, please consider offering your financial support, either by signing up for a paid subscription to this newsletter below, becoming a Patreon supporter, or sending a tip via PayPal or Venmo. It takes a tremendous amount of work to bring you stories like this, and I rely on your support to keep doing it. A monthly subscription is just $5!

Even if you can’t afford a paid sub, please sign up for a free one to get updates about this story, and please share this article on social media.

You can follow me on Facebook, Twitter, Mastodon, and Bluesky. You can email me at aquemere0@gmail.com.

You can read my original feature story about the James Carver case, which takes a deeper look at the evidence, here:

Science Proves Man Convicted of “Worst Mass Murder in Massachusetts History” Is Innocent, Lawyers Argue

James Carver is serving life in prison for a deadly fire but for decades has insisted he is innocent — and his lawyers say they have the scientific evidence to prove it

Anyway, that’s all for now.

What a great piece! Thanks for clearly tracking the dedication of the attorneys, and the realness of emotions, in this story of Mr. Carver’s wrongful conviction.

Congratulations on your excellent work on this story, Andrew! --Matthew Martens, Beverly Public Library